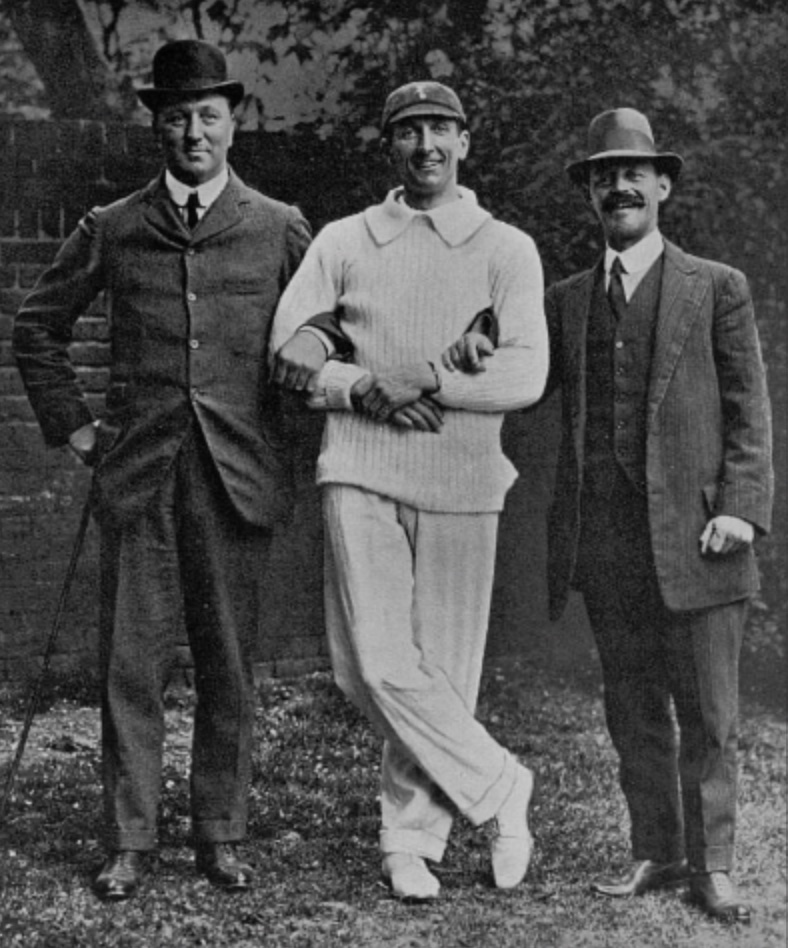

The three captains of the 1912 Triangular Tournament. Left to right: Frank Mitchell (South Africa), C. B. Fry (England) and S. E. Gregory (Australia). (Image: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 11 May 1912)

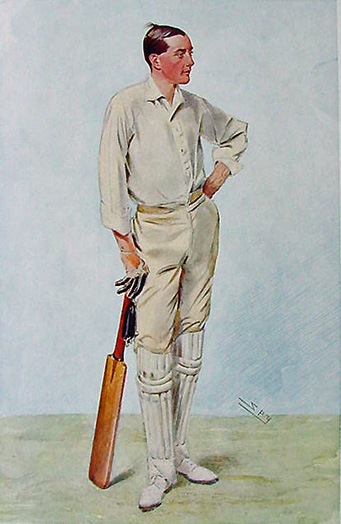

Even with various caveats and qualifications, there is little doubt that the list of achievements by C. B. Fry is impressive. A noted scholar in his youth; cricket and football for England; a joint world-record in athletics; “blues” in three sports from Oxford University. Nor were these his only interests: he dabbled in writing, politics and various other spheres, albeit with varied levels of success. He also had interest in the stage; he made an impact at Oxford as the Prince of Morocco in The Merchant of Venice — albeit more for his enthusiastic rendition of the line “Oh, Hell” than his acting ability — and was later fascinated by Hollywood, expressing interest in appearing in film. Yet there is a lingering air of dissatisfaction about his life; he came across as vain, arrogant and self-centred, while later in life he suffered from serious mental health problems. But he had a questionable relationship with the truth, as can be seen in his autobiography Life Worth Living, often wildly exaggerating his feats. For all the praise given in later years to his all-round sporting credentials, he never became part of the cricketing establishment in the same way as contemporaries like Pelham Warner or F. S. Jackson. Partly this may have been connected to his prolonged spell of mental illness in the 1920s (for example Harry Foster, Fry’s old Oxford team-mate, wrote to Gilbert Jessop in 1932 that he did not see him much anymore because he was “odd”). But there were other reasons; some of them were sporting but others were likely connected to his unconventional politics and personal beliefs.

Part of Fry’s problem was that when he was part of the cricketing establishment, he made a bit of a mess of it. This can be seen in his patchy record as a captain; despite being one of the few men to be undefeated as England captain, he was not convincing in the role. If he turned himself from an ordinary batter into an outstanding one through analysis and hard work, he never managed the same with leadership. At Oxford, his proficiency at sport meant that he was awarded the captaincy of the university football, athletics and cricket teams for his final two years, winning one and losing one of his matches against Cambridge in each of the three sports. But at university level in the 1890s, captaincy was as much a social role as a tactical one, and he had little impact on any of his teams. After leaving Oxford, he showed little appetite for cricket captaincy; he generally played under Ranjitsinhji for Sussex and under Archie MacLaren for England, concentrating purely on establishing himself as a top-class batter.

When Fry was appointed Sussex captain for the 1904 season, after Ranjitsinhji resigned owing to other commitments, the county dropped from second to sixth in the County Championship and over the following seasons never challenged for the title as they had around the turn of the century. The fault was not especially that of the new captain; the team had struggled for many years with a weak bowling attack and the loss of Ranjitsinhji between 1905 and 1907 was a heavy blow. However, his relationship with his professionals was strained. When he was just an ordinary member of the team, he viewed them largely as a supporting act that should not distract from his achievements. For example, he had forced Joe Vine, his opening partner, to become a very defensive player and had once admonished him for hitting three fours in one over: “[He] told me plainly that it was my job to stay there and leave that sort of cricket to him.” When Fry took over, he rarely took the time (and perhaps did not know how) to inspire or encourage them. Sometimes he even deliberately did the opposite, for example making Robert Relf go in as nightwatchman one evening in 1907 when he had already changed to make a quick getaway for an evening out in Canterbury,

A bigger problem was that he was often absent from the team owing to his many other interests, leading to an unsettled side. A ruptured achilles tendon in the second game of the 1906 season put him out of the team after two games and restricted him in 1907. By 1908, he appeared to have such little interest in playing for Sussex that it was picked upon by the press and there were frequent rumours he was going to retire. While he had a legitimate excuse, in that his time was taken up by the need to secure funding to keep the TS Mercury running, he was still the county captain but seemed unwilling either to resign or to commit to the club. The disharmony surrounding him meant that his spell as Sussex captain was not a success; it may not be a coincidence that he was never Hampshire’s official captain after moving there in 1909, although he performed the role several times as a stand-in.

Given his reputation and generally certain place in the side, Fry was often touted as a possible England captain. After a couple of occasions where he missed out, he was invited to lead the MCC team in Australia for the 1911–12 Ashes series. But his reputation was damaged further by this episode. He took weeks to decide whether to accept, which was not ideal from the prospective captain; the financial aspect of touring as an amateur was unappealing and he was not keen to leave the Mercury for so long. And there was a backlash when a Fry-endorsed appeal was launched by The Field to raise money to keep the Mercury running and free him up to tour; this attracted a huge amount of criticism and it generated little money. Fry eventually asked Field to end its campaign and he withdrew from the team. It was an embarrassing episode.

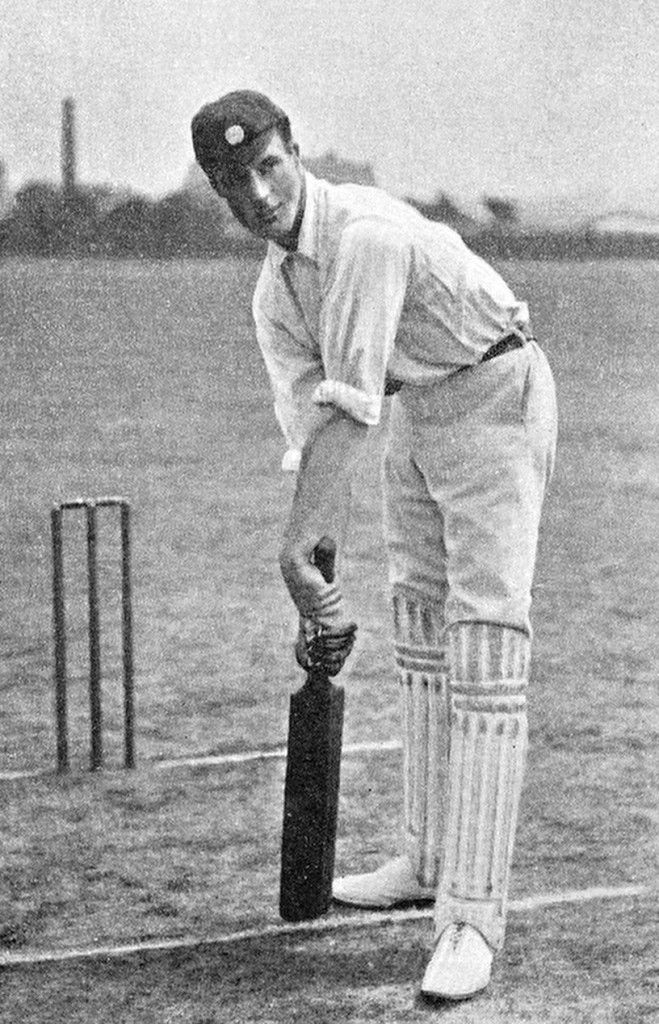

Fry’s only experience as England captain came the following summer, during the Triangular Tournament played between England, Australia and South Africa. Although past his best as a player, Fry was well positioned to lead England as he had been a keen supporter of Abe Bailey, who had been pushing for such a competition to take place since 1908. If the press questioned whether Fry was the best man to lead England at the age of 40, his association with Bailey and the newly formed ICC made him the ideal ambassador. Even so, the MCC appeared hesitant, and if we can believe Fry only offered him the role for the first Test. Fry’s version: he replied that he would only accept if given the role for the whole summer; Lord Harris, upon reading his letter, exclaimed “I think this fellow Fry is right!” As usual, it is a questionable account. Nevertheless, Fry led the team all summer and in the end was vindicated when England won the tournament. But this was not a particularly great achievement. The South African team was horribly weak and the Australian team barely representative after six leading players pulled out in a dispute with their board. Anything other than an English win in those circumstances would have been very unlikely.

But Fry did not impress on the field. He batted particularly nervously throughout the tournament, and seemed unhappy at several dismissals. And the pressure clearly got to him; the England wicket-keeper Tiger Smith later recalled that he missed two easy catches in the first game and took himself to the outfield away from the action in embarrassment. Nor were the press enamoured with his leadership. He was criticised for not bowling Frank Woolley, England’s most dangerous bowler in wet conditions, against Australia at Lord’s (although he later claimed the decision was tactical to prevent the Australians seeing Woolley’s bowling in a match certain to be drawn); and his delay in using Woolley against South Africa at the Oval was judged to be a tactical error later in the competition.

By the time of the decisive final game, against Australia, his relationship with spectators was at rock bottom. He was booed loudly at the toss for his part in a delayed start — he considered conditions unfit when the Australian captain wanted to play — and batted particularly poorly in the first innings. However, Australia collapsed to the bowling of Woolley; he was observed, according a 1984 biography by Clive Ellis, performing a handstand when a wicket fell. In England’s second innings, he scored a dour and chancy but important 79. Tiger Smith recalled many years later that Fry seemed unaware during his innings how bad conditions were — he was batting too well — and it was the professionals in the team who realised England’s best chance of an easy win was to get out quickly and bowl. Fry was critical of their approach, but they were proven right. Australia once more collapsed to Woolley, although Fry again behaved oddly. He was heard to shout for “George” (Hirst) to take a catch when the ball went in the air — but Hirst was not in the team. England won the game by 244 runs but Fry refused to come out onto the balcony when the spectators were cheering for him, remembering his treatment on the first day. As it happened, this was his final Test, and he ended his career never having lost a Test as captain; but he had been an unconvincing leader.

Even so, Fry was briefly a candidate to lead England during the disastrous 1921 summer, when he was 50 years old. But it was not his tactical skill that appealed; the desperate selectors were thrashing about for answers against an overwhelmingly superior Australian team, and Fry’s name promoted warm feelings of nostalgia and romanticism. The revival of his claims betrayed selectorial incompetence and showed their lack of awareness for what Test cricket had become in 1921.

If there were question marks over Fry’s captaincy, there were even bigger ones over his role as a Test selector. Owing to the way that committees were composed, Fry was a selector several times. In 1899 and 1902, he was part of the committee through being one of the first amateurs picked for the England team; in 1909 and 1912 (in the latter season as both chairman of selectors and England captain) he was a permanent selector. As ever, Fry was eager to inflate his importance in Life Worth Living. For example, he claimed (not very convincingly) that in 1899 he unwittingly had the casting vote in choosing Archie MacLaren to replace W. G. Grace as England captain. In his version of the selection meeting for the second Test, Fry arrived late and when he was asked by Grace if he thought MacLaren should play, he said yes without knowing that the others had been deadlocked over whether Grace or MacLaren should be captain. Fry believed that he therefore was the man who ended Grace’s Test career. But as usual, we cannot trust Fry, and it would have been perfectly possible for both MacLaren and Grace to play.

The England team for the first Test of the 1902 Ashes. Back row: G. H. Hirst, A. A. Lilley, W. H. Lockwood, L. C. Braund, W. Rhodes, J. T. Tyldesley. Front row: C. B. Fry, F. S. Jackson, A. C. MacLaren (captain), K. S. Ranjitsinhji, G. L. Jessop. (Image: Archie (1981) by Michael Down)

Fry’s next experience in the role came in 1902. As in 1899, he was co-opted onto the panel through being one of the first amateurs picked. But in retelling his role in that Test series, Fry was aware that the selectors had been heavily criticised for their negative influence over that summer and so attempted to absolve himself from any part in the mistakes. As it happened, he was only a selector for the first two Tests (he was a late replacement in the third game and was dropped for the final two after scoring 0, 0, 1 and 4 in the series), but rather than explain this, Fry chose to portray himself as the lone voice of sanity that summer. He was critical of the selectors’ tendency change the team owing to the unsettling effect on the players; as he was dropped, this is hardly a surprising view. But he emphasised how correct Archie MacLaren, the captain, was in his opinion that Gilbert Jessop — dropped for the fourth Test before scoring a match-winning century in the fifth — was an indispensable part of any England team.

He wrote a detailed account of the selection meeting for the fourth Test in which Fred Tate was selected largely owing to a clash between MacLaren and Lord Hawke, the chairman of selectors. He said that Hawke had not allowed Schofield Haigh to be chosen as it would affect the Yorkshire side, which already had contributed three players to the England team. According to Fry: “When someone proposed Fred Tate instead of Schofield Haigh, I distinctly told my colleagues that Fred Tate could not field anywhere except at slip, and that, though he was a careful slip in a county side, he was not up to the standard required in a Test Match. Lord Hawke was huffy, and we gave way to him, me protesting.” Tate, of course, dropped a crucial catch in that game and was harshly judged as being to blame for England’s three-run loss; retrospectively (and a little unfairly) he was judged as having been an ill-judged selection, out of his depth at Test level. If we believe Fry’s account, he had seen this and attempted to stop it. It is a beautiful story, but Fry was not a selector for that Test match, having already been dropped and not being a permanent member of the panel. This discussion is nothing more than a figment of his imagination, another product of his compulsive need to be the hero of every story; even so, the tale was frequently retold in later years as if it were true and still can be seen unquestioningly included in accounts of the series.

There were similar criticisms in 1909, when Fry was one of the permanent selectors. That panel has been ridiculed as one of the worst of all time, drawing comment from Sydney Pardon in Wisden that one of their decisions “touched the confines of lunacy”. Some of the worst decisions were made before the second Test, when the chairman of selectors, Lord Hawke, was recovering from a long illness in France. Apparently going against the wishes of the captain MacLaren, the two remaining selectors — Fry and H. D. G. Leveson Gower — dropped Wilfred Rhodes and Gilbert Jessop, two men generally guaranteed a Test place in this period. Even worse, despite making five changes to the team that won the first Test, they failed to pick a fast bowler in helpful conditions. Fry, in his autobiography, unconvincingly tried to abdicate any responsibility, although he still claimed credit for the partially successful inclusion of Albert Relf. Pardon in Wisden lamented: “Never in the history of Test Matches in England has there been such blundering in the selection of an England eleven.” Even when Hawke returned, the choices made by the panel were vehemently criticised for the rest of the season.

If his final term as a selector, for the 1912 season, was more successful on paper, Fry still felt the need to prove himself in Life Worth Living. He claimed that he had insisted on being the chairman and that the rules were changed so that only two other selectors could join him. He also wrote that they met only once, and chose “a definite team with definite substitutes if required for the whole series of six matches and we never met again.” This is likely another exaggeration, and Alan Gibson in Cricket Captains of England (1979) notes that there are “stray references” that other meetings took place. Iain Wilton, in his 1999 biography of Fry, notes that 17 players were used by England that summer which, if it was not an unusually high number for the period, indicates less stability of selection that Fry indicated. Nor were all the selections an unqualified success; the weakness of the opposition meant that errors were not as costly as in previous summers.

Aside from the damage to his reputation from his selectorial misadventures, there was another blot on Fry’s cricketing copybook. He turned to writing early in his career as a way to supplement his meagre income. To a modern audience, Fry’s writing is usually quite readable, especially his later work. But some of it can be impenetrably dense, and his style often seems contrived. For example, writing about how rain affected cricket pitches in 1902, he said: “It sounds artificial, but, by Hercules! the idea of covering up the wicket with a big tarpaulin is not so very unreasonable.” But he was undeniable prolific; he contributed articles to various publications and authored his own books, particularly on cricket technique. For a few years at the start of the twentieth century he had a regular column in the Daily Express, writing about matches in which he was playing (including the 1902 Ashes series). Although he was not alone in doing this, it was frowned upon by the establishment. In later years, he contributed to magazines, including ones aimed at boys — notably The Captain — and in 1904 became the editor of a new publication named after him — Fry’s Magazine. This often featured articles which reflected Fry’s own interests, such as motoring or flying, and promoted the virtues of sport. His involvement in the Boy Scouts movement— he was a friend of Robert Baden-Powell — also prompted him to argue that Britain should focus on sports with greater military value, such as shooting. Although not an especially unusual belief at the time, Fry’s advocacy of militarism did not escape attention — and occasional ridicule. He later reduced his commitment to magazine when the TS Mercury took up more of his time and resigned as editor in 1910. He continued to write occasional articles but the magazine ceased production when the First World War began. Not for the first time, Fry had dabbled in a new world but failed to emerge quite on top.

His other literary achievement before the war was a novel, written with his wife, called A Mother’s Son. The book was well-received by critics and praised by some of Fry’s admirers in later life, but seems to have been horribly cliched and dripping in purple prose. Wilton said of it: “The book can only be regarded as a page-turner on the basis that readers will want to escape some sections, which are cringe-inducingly bad.”

After the long seclusion caused by his mental illness in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Fry returned to journalism. He began to write for the Evening Standard in time for the 1934 Ashes series. The newspaper had also signed Douglas Jardine for that summer. The latter was to write the “straight” reports on the matches while Fry was to write something more idiosyncratic, producing columns supposedly in an impressionistic, “American” style. The result, a column called “C. B. Fry Says” proved very popular. He made an impact in the press box too, arriving by chauffeured car and sharing his enormous lunch from a hamper. He opened his first column with: “Full of people, all talking. No interest in Bradman’s broken shoelace at Suez. Or Woodfull’s fall on the deck at Crete. It’s just the age-old love of cricket and expectations.” It was in this column that Fry first called Bradman “The Don”. He wrote of him in the 1934 series: “He smashes with a sort of sardonic smile in his strokes.” “C. B Fry Says” was perhaps his greatest achievement away from the field of play, but even in this success there was controversy, because he felt the need to score points.

He managed to alienate the Australian cricket team on several occasions. For example during their match against Cambridge in 1934, he wrote: “Australians seem to be quite nice people. We, the elite, stay at the famous Bull. The actual players are at the University Arms.” His biographer Ellis noted that his articles often contained “subtle taunts.” He irritated the 1938 Australian team by suggesting that they were unsporting and took the game too seriously. And he often commented on the education of Australian players, lamenting that only a couple had been to public school, and made snide comments about their occupations away from cricket. Given the ruptures caused by the Bodyline controversy of 1932–33, and the exaggerated care taken by the MCC to avoid giving offence to the Australians in the strained aftermath, Fry’s careless snobbery and taunts must have raised a few eyebrows at Lord’s.

C. B. Fry (extreme right) and Ranjitsinhji (centre left, in profile) at the League of Nations (Image: C. B. Fry: An English Hero (1999) by Iain Wilton)

Fry’s politics probably killed any last chance of admittance to the Lord’s establishment. He began respectably enough. In the early 1920s, he worked with Ranjitsinhji at the League of Nations, although he was thought to be behind several incidents where his employer made complaints about the lack of deference according to him. It was during this time that Fry was supposedly offered the throne of Albania, an episode he described at length (and with uncharacteristic restraint, suggesting that for once he was being accurate) in his autobiography. He believed he had a good chance, but would have needed Ranjitsinhji to support him to the tune of £10,000 a year, which the latter was unwilling (and realistically unable) to do. There have been various explanations of this, from an elaborate joke by Ranjitsinhji that got out of hand, to something entirely fabricated by Fry. But most writers, most notably Alan Gibson who dug into the story in some detail, have concluded there was some truth in the tale, and the Albanians were undoubtedly looking for a king in this period.

Fry’s supposed interest in social issues such as public health meant that he was of interest to political parties and there were occasional suggestions during his cricketing days that he would enter parliament. After the First World War, he stood as a Liberal candidate in three elections, adopting unconventional tactics such as campaigning on horseback. Hampered by his political inexperience and an unfamiliarity with the Liberal manifesto, he lost fairly convincingly at Brighton in the 1922 General Election, narrowly at Banbury in the 1923 General Election and then again at Oxford in a 1924 by-election. In the latter two elections, he was affected by split votes lost to the Labour candidate. At Banbury the stresses caused his health to break down and he missed the declaration. He made no mention of these episodes in his autobiography, and his entry into politics is usually explained as him attempting to conquer a new world having finished with sport. But the question remains: why did he stand in three elections? Did he look at the achievements of those with whom he went to university, or against whom he played cricket, and feel that he needed to prove himself as more than a sportsman? In that case, his choice of the Liberal Party may have been a mistake. Although Fry was far from the only cricketer to enter politics, the natural sphere of the MCC was the Conservative Party and it is unlikely he did himself any favours associating with the Liberals. Yet the final nail in the coffin of Fry’s establishment status probably came through his later association with right wing politics.

Unlike modern readers, Fry’s contemporaries would not have batted an eyelid at his association with Robert Baden-Powell or Abe Bailey, both men were unashamed imperialists and white supremacists. Nor would Fry’s push in his writing for a more militaristic focus in Britain have been seen as necessarily wrong. And leading members of the cricketing establishment, including a captain of England, flirted with fascism in the early 1920s without any detriment to their status. But Fry became associated with the extreme right when it had lost a lot what little lustre it had after revealing its true colours in Italy and Germany. Showing tone-deafness that was one of his defining characteristics, on the eve of the Second World War, Fry devoted a whole chapter of Life Worth Living to a meeting he had with Adolf Hitler in 1934.

The background was attempts in Germany to cultivate links between the Hitler Youth and the Boy Scouts movement. When the approach failed, Fry — who had long been a supporter of Boy Scouts and had almost been the figurehead when the movement was launched — was invited to Germany. When he arrived, he spent time at the Ministry of Propaganda and met Hitler for around an hour (which Fry had insisted was a condition of his agreeing to visit), listening to his “vision” and his view of the threat of Communists and Jews. Fry was impressed, which might have been seen as unfortunate but not unforgivable in 1934. But what Fry said in 1939 was highly questionable, then and now. He wrote favourably of the devotion of the German people to Hitler and the discipline in the atmosphere. He liked this version of Germany, and openly said so: “Herr Hitler and his men genuinely wished to be friends with us.” And he liked the man himself, writing that he “gave the impression of effective grip” and admitting that he was “attracted by him”. Even when the true nature of Nazism had become apparent in 1939, Fry still was happy to conclude that the effect it had produced in Germany was a good one; he said that the way Germans “did face and outride” the “storm” of “Communism and its corollaries” which “are a turgid curse of mankind” was “a tremendous feat of national character”. He was still in favour of building links in the respective youth movements. Nor was this a one-off for his autobiography; he wrote in the Sunday Express in 1940 of his continued admiration for Hitler.

Fascism clearly had an appeal to Fry, and it was one he explored after visiting Germany. Although he was not a member of any fascist party — and he would not have been the first cricketer to join one — he attended a meeting of the British Union of Fascists as a guest in 1934, allowed members of the Hitler Youth to use the Mercury and watched film of the Berlin Olympics at the German Embassy. After the war, he downplayed his support, suggesting that he told Hitler that he should not invade England and instead recommended that Germany take up cricket.

But perhaps the damage was done. Fry would never have been entirely acceptable to Lord’s: a journalist; a difficult personality; an unapologetic snob; someone who loudly insisted on the deference he felt was his due; a man who exaggerated and blustered his way though conversation and writing; an overly garrulous, oddly dressed eccentric who had suffered from prolonged mental illness; and a supporter of Hitler just before the outbreak of a terrible war. No number of runs could quite compensate to the people who mattered.

C. B. Fry receiving his “big red book” from Eamonn Andrews when he was the subject of the TV programme This is Your Life in 1955 (Image: Big Red Book)

None of this makes Fry an appealing character. Much more could be said about his life, about his interests and the varied spheres in which he worked and moved. Others have done so at great length. But underneath the surface, there is something uncomfortable about the man. One of the most insightful pieces of writing on Fry — before the warts-and-all biographies by Ellis and Wilton — came from Alan Gibson. In his 1979 Cricket Captains of England, he said: “A business partner of Fry’s, Christopher Hollis, wrote to me … that C.B. ‘had a great capacity for living a fantasy life’. He went on, ‘It pleased him to tell the story [about the offer of the throne of Albania], and by the end I fancy that he did not know himself whether he believed it or not.’ While one does not doubt the truth of this, it would be a mistake to think that Fry was a fantasist, in the sense that Walter Mitty was. His fantasies were no more than embroideries on what was already the finest silk. His achievements were real.” Gibson wrote admiringly of Fry but noted that his character contained “not exactly an acidity, but a certain mordancy, a classical disdain”.

Another viewpoint was that given by his wife — who died in 1946 and left him free to become a genial celebrity around the radio and television circuit — that his mental illness of the 1920s was caused by “thwarted genius”. Perhaps he spread himself too thinly and never achieved what he believed what he was capable of. While his contemporaries, cricketing and otherwise, went on to bigger and better things, he stagnated. And maybe Gibson realised this, telling a story of how one of his Oxford contemporaries, F. E. Smith who became Lord Chancellor, visited the TS Mercury: “[Smith] was duly impressed, and ended by saying ‘This is a fine show, C.B., but, for you, a backwater.’ Fry replied, ‘That may be, but the question remains whether it is better to be successful or happy.'”

Was Fry happy? His marriage was undoubtedly not, nor did he really have a role in running the Mercury, which was the domain of his wife. His character betrayed defensiveness and his writing a desire to magnify his achievements and promote a vision of infallibility. If his “life worth living” was a constant search for fulfilment — in sport, or literature, or politics, or conversation — the evidence suggests that he never succeeded in finding it.