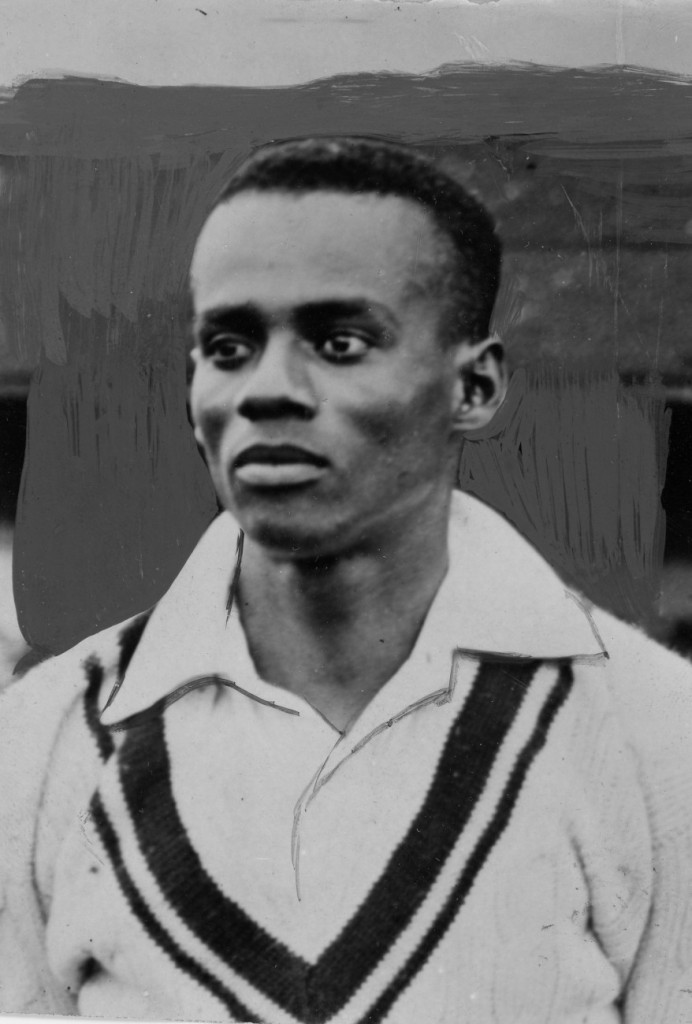

Edwin St Hill during his time at Lowerhouse

(Image: Burnley Civic Trust Heritage Image Collection)

Edwin St Hill appeared in two Test matches for the West Indies, played for Trinidad in the Intercolonial Tournament between 1924 and 1930 and was a regular for Shannon, the cricket club made famous by CLR James in Beyond a Boundary. His first-class career was over before he reached the age of thirty, resulting in his disappearance from most cricket records. But tracing his life afterwards reveals a whole new chapter. Between 1931 and 1933, St Hill played professional cricket for Lowerhouse in the Lancashire League. Only the third West Indies player, after George Francis and Learie Constantine, to appear in English league cricket, St Hill was also one of the few overseas players in the leagues who had not played cricket in England beforehand. He and his wife Iris, who joined him in England, made a life for themselves in the town of Burnley. The move was a gamble both for him and for Lowerhouse, but his three years there were largely successful on and off the field. He clearly enjoyed his time in Burnley, and was a popular local celebrity, becoming involved in local life.

A combination of financial pressure and St Hill’s loss of form meant that Lowerhouse signed another professional for 1934. St Hill could have returned permanently to Trinidad and Tobago but instead looked for a new club, clearly intent on remaining a professional cricketer. Based on contemporary newspaper reports, there may have been some competition for his signature, but eventually he settled on a lucrative deal with Slaithwaite, a club in the Huddersfield and District League. His time there was partially chronicled in a project run by Huddersfield University called “The Cricket History of Calderdale and Kirklees” (the website to which is dead, but the pages relating to St Hill at Slaithwaite were archived), which allows us to fill in some details. He was by far the most famous professional Slaithwaite had ever signed. His one-year contract was worth £240 – the highest recorded in the Huddersfield League until then – plus a benefit match. This compared very favourably to the wage for a county professional – even at the richest counties, most players would only be paid around £300 – and was roughly equivalent to wages in the Lancashire League (although there were exceptions for star players such as Cecil Parkin, who earned £300 for Rochdale in 1919 and Constantine, who was paid £750 by Nelson in 1935).

If the cricket played in Huddersfield did not match the high standards of the Lancashire League, it was certainly competitive. But St Hill’s profile was considerably lowered by moving to a mid-table club in a league with no great reputation. Did this affect the remainder of his career? Possibly. But it is also possible that his best years as a bowler were behind him.

Edwin and Iris St Hill at Slaithwaite (on a cold day judging by their outfits), joined by their dog

(Image: Leeds Mercury, 20 February 1934)

After spending some of the winter in Trinidad, St Hill and his wife moved to Slaithwaite for the 1934 season. As had been the case at Lowerhouse, he arrived in a blaze of publicity, and photographs were taken of him and Iris outside their home on Royd Street in Slaithwaite. Among the photographs were ones featuring a car and a dog, both of which presumably belonged to them. Iris is not smiling in any of the pictures, in contrast to the one taken when she joined her husband at Lowerhouse. In fact, she looks distinctly unhappy. There may be reasons for that, as we shall see.

On the field in 1934, St Hill was successful enough. Slaithwaite shared the league title with Golcar; St Hill scored 408 runs at 20.40 and took 87 wickets at 12.91. The Lancashire Evening Post kept track of his performances, noting one game in which he took seven for 15 and another in which he took a hat-trick, but reported that many catches had been dropped off his bowling. The Slaithwaite annual report was, however, slightly lukewarm: “The engagement of St Hill has been successful to a point, and we claim it has brought increased interest into the League.”

This may be unduly faint praise; a report in the Burnley Express, still taking an interest in their former local professional, filled in more details. St Hill had attracted great interest, and his signing was regarded as “revolutionary”. But Slaithwaite simply could not afford his wage. Although his presence had greatly increased attendances, the rules of the competition meant Slaithwaite did not receive anything from away games. Consequently, they were making a financial loss. In August, the club decided not to renew his contract, but his benefit match was a success, as a team chosen by Constantine and featuring the West Indies batsman George Headley played Slaithwaite in front of a crowd of 5,000. There was also one off-field drama: St Hill was ordered by a magistrates’ court to pay income tax arrears that, by October 1934, amounted to £3 12s 6d.

Iris and Edwin St Hill, pictured outside their home on Royd Street, Slaithwaite, in 1934; the date is unknown but judging by their clothing, it was during the summer (Image: The Cricket History of Calderdale and Kirklees)

As Slaithwaite decided quite late not to re-engage him, St Hill had not secured a position by the end of the 1934 season, advertising his services in early August in the Yorkshire Post and giving his address as 60 Royd Street, Slaithwaite. Even as the 1935 season began, he was practising at his old club, perhaps still trying to secure a deal. Perhaps he hoped to return to the Lancashire League, but if so he would be disappointed. Instead, he moved to another league in West Yorkshire, the Bradford League. The standard here was perhaps a little higher than Huddersfield, although still short of the quality of the Lancashire League. Coverage in local newspapers allows us to piece together most of St Hill’s subsequent career, albeit patchily. The few gaps in his time in the Bradford League have been filled in with the generous help of the current Bradford League Records Secretary, Mike Rhodes. The only information lacking is how much he was paid in these later years.

For 1935, St Hill joined East Bierley, a club just south of Bradford. He also played some evening matches for Lockwood in the Huddersfield League. As East Bierley, Lockwood and Slaithwaite – where he was presumably still living – are some distance apart, his season must have involved a lot of travelling. We do not know whether he stayed in Slaithwaite for subsequent seasons, or moved closer to Bradford, but it is certain he lived in England for the rest of his life, and never returned to Trinidad.

St Hill was a success for East Bierley. The history of the club on the Bradford Cricket League website describes him as a “legendary performer”. In 1935, he finished 12th in the League bowling averages with 63 wickets at 14.57, as his club finished third. Given his form and popularity, he re-signed for 1936. That season, he had a benefit match for which Constantine again brought a team. In total, St Hill took 87 wickets at 10.60 during 1936, including eight for 50 against Pudsey St Lawrence, but despite his efforts the club dropped to fifth in the table.

St Hill did not remain at East Bierley. In August 1936, he signed a deal with Lascelles Hall, a club in the Huddersfield League, for the 1937 season. Whether the choice was his or that of East Bierley is unclear, but it is not impossible that finances were once more a factor. Or perhaps, if he still lived in Slaithwaite, Lascelles Hall was simply nearer to home. But matters did not quite work out as intended. St Hill only played a few matches in 1937: by mid-June, he had been admitted to Huddersfield Royal Infirmary with what newspapers described as an “internal complaint”, one which was still a problem in July. Another professional stood in at Lascelles Hall, but St Hill was still given a benefit match. Although unable to appear personally, Constantine again organised a team; his players included the Indian Test bowler L Amar Singh, who had signed for Colne in the Lancashire League. With both Constantine and St Hill absent, it is hard to see that the match was a success.

East Bierley Cricket Club (Image: Bradford Premier League)

Spen Victoria Cricket Club (Image: Bradford Premier League)

In January 1938 St Hill was announced as the professional for Spen Victoria in the Bradford League. His new club was situated near Cleckheaton, not too far from East Bierley. The history of Spen Victoria on the Bradford League website notes that St Hill was the first Test player to represent the club, although it mistakenly says that he played for them in 1937. Once more, his signing resulted in a good league position for his club, which finished sixth in 1938 and third in 1939. In his first season, St Hill took 42 wickets at 17.66, 27th in the league averages and only second for Spen Victoria. If this was underwhelming, he was perhaps not back to his best after his illness, because he was much more effective in 1939. His best performance that season was nine for 50, as he took 59 wickets at 10.72 and was the first bowler to reach 50 wickets in the season.

Three events stand out from this period at Spen Victoria. In 1938, his benefit match again starred Constantine, who brought a team which included his brother Elias, then playing cricket in England, Amar Singh and the latter’s Test colleague Lala Amarnath, who had replaced Constantine at Nelson. A few weeks later, St Hill took most of the same players, including the Constantine brothers, to play Huddersfield in a match to raise funds for Huddersfield Royal Infirmary, presumably as a gesture of thanks for his treatment during his illness the previous year. The following year, St Hill had trouble with a crowd for the only time on record – and revealed some of the fire which his brothers Wilton and Cecil possessed. In a match at Windhill, play resumed late in the day after rain, and while St Hill was drying the ball with sawdust, he was barracked by the crowd for time-wasting. Obviously unhappy with the remarks, St Hill dipped the ball in more sawdust every time there was a shout, slowing the game down. The match was drawn when time ran out, but the local newspaper was not critical of St Hill, blaming the barrackers for their team’s failure to win.

When the Second World War began, St Hill almost immediately joined the army and by December 1939 was stationed in France. In 1940, he took part in the Dunkirk evacuation, of late May and early June but what happened to him afterwards is unclear. He played at least once for Spen Victoria in 1940 (his figures for the season were 12-0-90-1), and there is a record of him playing for Heanor Town in the Border League in July and August 1940 while “on military duties”. The Nottingham Evening Post rather inaccurately described his games for Heanor Town as his first in England. St Hill was also in London in August, playing for a “West Indies XI” against “Pelham Warner’s XI” at Lord’s.

But at this stage, St Hill becomes a little difficult to track. The only information I have on his military service comes from Cricket’s Wartime Sanctuary, a book on the Bradford League in wartime by Tony Barker – and it is not clear from where Barker’s information comes. St Hill was apparently demobilised at some point in 1941; again, we do not know why. Perhaps he was injured; perhaps his health, related to his 1936 illness, was an issue. After this, he resumed cricket, and returned to play for Spen Victoria for the 1941 season, taking 44 wickets at 17.43 to finish 31st in the averages. One other snippet survives from this time, when St Hill once more found himself before magistrates regarding non-payment of tax in March 1942. He revealed that he had fallen behind in his payments after his discharge from the army, but was working as an assistant machinist in Bradford; he offered to increase his repayments once the cricket season began.

League cricket coverage in newspapers was, unsurprisingly, not extensive during the war, but it is still possible to sketch an outline of St Hill’s cricket. For example, wartime annuals of the Cricketer gave a good overview of various leagues throughout England. St Hill continued to play for Spen Victoria in 1942, taking 36 wickets at 17.02 (finishing 23rd in the league averages). This was his final season in the Bradford League, but his overall record was good; in total, he scored 758 runs at 12.63 (which does not include the 1939 season, for which his batting figures are unknown) and took 332 wickets at 14.11.

For 1943, St Hill returned to Lancashire, playing in the Central Lancashire League for Crompton in 1943 (when the Cricketer said that he had “another good season” but did not give his figures) and 1944, when he took 49 wickets at 12.65 (when the Cricketer judged his performance as “less successful than usual”). As the war drew to a close, St Hill returned to Slaithwaite for 1945. If the records of The Cricket History of Calderdale and Kirklees are correct, he took 65 wickets at 6.72; in one match, he took eight for 26 where all his wickets were bowled.

These wartime performances of St Hill look good on paper, and he would have faced many first-class and Test cricketers in the various leagues which were the only paid cricket available. However, the teams cannot have been as strong as they were in peacetime; additionally, as St Hill was 41 when the war ended, it is unlikely he was as effective as he had been ten years before. It is most likely his figures were improved by facing weak opposition.

But this was not the only cricket he played. He also took part in many wartime charity games, mainly for teams of West Indian cricketers, which featured leading cricketers. He appeared three times at Lord’s – generally the most prestigious charity matches – for the “West Indies XI” and played several times in teams selected by Learie Constantine. In total, CricketArchive records him playing in 30 such matches between August 1940 and August 1945. In these games, he scored 236 runs at 11.23 and took 35 wickets at 21.84, which may be a better reflection of his ability in this period. He also played in a team organised by Constantine that toured Scotland in 1946.

By this time, St Hill had joined yet another club – his seventh in England. He signed for Walsden in the Central Lancashire League for 1946, at which point, he finally disappears from the radar with his greatest cricketing days behind him. His Wisden obituary stated that he played in the Central Lancashire League between 1943 (which is clearly a mistake) and 1951. But around this time, he certainly played in the Bolton League for Kearsley; when Jack Bond was named as one of Wisden’s Cricketers of the Year in 1971, the citation stated: “[Bond] pays tribute to the coaching he received on his way up from … the Kearsley professional, Edwin St Hill.” Bond was born in 1932, and joined Kearsley aged 16, so this must have been some time after 1948. St Hill was also the reserve professional for Slaithwaite in 1947.

But for these relatively minor leagues into which St Hill had slipped, few records are available. Tracking the teams for whom he played, never mind finding details of his playing record, is all but impossible. The last record for St Hill on CricketArchive is a match in which he was the professional for Vickerstown, a club in Cumbria which played in the Cumbria Cricket League, when they lost to Workington in the 1952 Higson Cup final; St Hill scored 25 and took four for 82.

Meanwhile, St Hill continued to play for “West Indies” teams, often with Constantine, and sometimes captained them; he was usually accompanied by several former Test players, including EA Martindale and EA Achong. As late as 1951, he appeared alongside some stars of the 1950 West Indies tour – Worrell, Weekes, Walcott and Ramadhin – for a West Indies team that played a charity game at Barnoldswick. He appeared for similar teams against Vauxhall Motors in 1953 and 1954. In 1954 he also played for “James Nelson’s XI” in a friendly match at Nelson Cricket Club.

What was he doing away from the cricket field? To supplement his income as a professional cricketer, he almost certainly had other jobs. We know that he was an assistant machinist during the war, but afterwards is a mystery. There are no records of where he worked, or even where he was living, until his death in 1957. These fragments are all we have.

Another mystery is what happened to Iris. There is strong evidence that the couple split long before St Hill died. And here, we may just be able to pinpoint a reason. On 28 July 1933, an 18-year-old from Burnley called Margaret Close gave birth to a girl she named Norma. According to Norma’s family, her father was Edwin St Hill, but he was not listed on her birth certificate, and played no part in her upbringing. As usual in these cases, there is no definite proof apart from the certainty of the family. It is not known whether St Hill ever had any subsequent contact with Norma or her mother, or how much he knew about what happened. Norma was raised by her grandparents, and in 1939 was living with them while her mother, who had married, lived elsewhere.

If St Hill was her father, it dates his relationship with Margaret Close to the winter of 1932, the first he spent in England. It is not hard to imagine circumstances – particularly with St Hill’s fame in Burnley and his social role as the Lowerhouse professional – where something may have happened. Does this partially explain why he moved to Slaithwaite rather than remain in the Lancashire League? To put some distance between him and Burnley? The other obvious, but unanswerable question, is how much did Iris know? Presumably, she would have found out, and it must have put a huge strain on the marriage.

Edwin and Iris St Hill, and their dog, at Slaithwaite

(Image: Yorkshire Evening Post 19 Feb 1934)

However, the couple stayed together at first – she certainly moved to Slaithwaite with St Hill. From this point, we cannot be sure of their status. On the only official record, the 1939 Register, Iris A St Hill is living in London, working as a cook. Describing herself as married, she was living in what appears to be a boarding house, along with, among others, an artist and a professional wrestler. There is no record of her husband at all on the 1939 Register, which suggests had already joined the army (although he was still playing cricket in late August for Spen Victoria) when it was taken on 29 September; military personnel were not included in that record. The question arises whether Iris had been living in London with her husband – perhaps he was there in some connection with the army – or was living apart from him. Perhaps they had separated by this stage, but we cannot be sure.

All we know for certain about St Hill’s final years are the facts recorded on his death certificate. He was working as a clerk at the Ministry of Fuel and at the time of his death lived at 20 Swinbourne Grove in Manchester, which was almost certainly a boarding house. He died on 21 May 1957, aged only 53 (although his death certificate said 51). He suffered a stroke and never woke up: the cause of death was listed as a coma and cerebral hemorrhage. His death was registered by a lady called Violet Bibby, who was “causing the body to be buried” – the person organising the funeral. Her address was also 20 Swinbourne Grove, which may indicate that she was a landlady, or somehow connected with the house. The death certificate does not call him a cricketer or retired cricketer; perhaps Violet Bibby was unaware of his past. In his will, St Hill left £1,219 14s 7d (worth nearly £30,000 today) to a grocer, Alfred Charles. The absence of his wife – from the death certificate, from any funeral arrangements and from his will – indicates fairly conclusively that the couple had split up by 1957, and probably long before that.

According to CLR James, St Hill’s brother Wilton also died in 1957; although the date is uncertain, an article by Learie Constantine in the 1957 Wisden (published on 30 April) said that Wilton was dead. So the two brothers died in the same year, and Edwin did not live long after Wilton. There was one other coincidence about St Hill’s death: it came just as the West Indies team, containing several men who played alongside him in charity games, was starting a tour of England.

Oddly, there was no mention of St Hill’s death in the Cricketer, nor in any newspapers currently available online. He was buried around 2pm on 24 May in Manchester’s Southern Cemetery (close to what appears to be a part reserved for foreign nationals); for some reason, his burial record gives his occupation as “retired”. His grave is currently unmarked. It is a long, long way from the Queen’s Park Savannah in Trinidad.

In another section of the same cemetery, at the other side of the access road, Iris Agatha St Hill, nee Orvington, is also buried in an unmarked grave. She never remarried, and her death certificate lists her as the “widow of Edwin Lloyd St Hill, clerk”. She died at the Park Hospital, from a combination of cancer and heart disease, on 27 November 1987 at the age of 81. She left £1,138, worth around around £3,000 today. She had been living at 71 Newbury Avenue in Sale. The informant “causing the body to be buried” was Gwendoline Ebanks of Fallowfield. As Iris’ certificate does not give her former occupation nor mention any details about her late husband other than those recorded on his death certificate, I wonder if Ms Ebanks knew much about her. It is unclear whether they were buried separately on purpose because they were separated, or because whoever organised her funeral did not know where Edwin was buried.

There is a certain sadness that both Edwin and Iris lie in similarly unmarked graves so close to each other, perhaps 200 metres apart. That neither had any family to bury them is equally sad. The remainder of Iris’ life between 1957 and 1987 is a complete mystery, although she had evidently moved to Manchester. I do not know if she ever returned to Trinidad and Tobago, but having come to England with her husband she lived there for the rest of her life.

What do we make of Edwin St Hill? Given how much of his story is dominated by cricket, and statistics, there is a danger that he just becomes the thing he was described as in his early days – a bowling machine. But all through his career, no-one appears to have had a bad word to say about him. He was popular at Lowerhouse, at Slaithwaite, at East Bierley and at Spen Victoria; the press in Burnley praised his attitude and approach. He threw himself into the role of professional at each club. Other cricketers were friendly with him: his benefit matches always attracted the biggest overseas stars in league cricket, wherever he played at the time; Constantine was close to him, as was George Headley; Jack Bond spoke highly of his coaching; in almost every surviving photograph, he is smiling warmly.

He appears to have been a very popular man who nevertheless died alone. This gives the impression that he was very different to his brothers. What of the “fire” that drove Wilton? Or the streak that led Cecil to provoke George John into a rage? But it is hard to imagine either of them making the success of the career of journeyman professional that sustained Edwin from 1931 until the early 1950s. Perhaps there is a hint of Wilton’s attitude in the way he stood up to the crowd at Windhill when they barracked him; or maybe his love of boxing was the outlet for any aggression. But what about his illegitimate daughter? How do we fit her into the picture of who St Hill was? And the evident failure of his marriage? The evidence may hint at someone with hidden depths not expressed in his cheerful public persona. But these can only be hints; we will never know the full picture.

There is a danger that Edwin St Hill falls between several stools. He was not worshipped by the people of Trinidad and Tobago, nor the subject of a chapter in cricket’s most famous book, like Wilton. His first-class and Test career was respectable but does not demand a re-evaluation of his worth as a top-class cricketer. Even his record in league cricket, although a good one, does not catch the eye; he was normally some way down the averages in each league. He could not be called a pioneer for West Indian cricketers because Constantine – and to a lesser extent George Francis – had paved the way before him. And unlike Constantine he made no wider impact – unlike Constantine, he did not follow his cricket career with forays into the world of law, politics and become a campaigner for racial equality.

And yet… few people could match Learie Constantine – that is probably impossible. Failing to do so does not make Edwin St Hill any the less.

Because here was a man who came to live in England having never visited it. A man who joined a cricket league about which he knew nothing but was confident enough to make a success of it. A man who, if he never scaled the heights of Constantine or Headley, sustained a career for over twenty years. A man who fitted in wherever he went and was successful at each club. A man who fought in the war. And a man who lived most of his life, worked and died over 4,000 miles from where he was born. Unlike Constantine, we do not know of the difficulties he faced in a new country; we do not know what challenges he overcame; we do not know how much racism he faced in his everyday life, even though it is inevitable he faced plenty. While he never achieved Constantine’s fame, he became a familiar figure in the northern leagues, and the scanty references to him in later years suggest that he was a well-respected one, as does his continued association with West Indies teams until shortly before his death.

Forgotten today, I think Edwin St Hill deserves rather more; not least some kind of memorial over his grave. As does his remarkable wife, who would have faced the same challenges without the security of cricket fame to protect her, and may well have endured considerably more before striking out on her own. It seems sad that these two remarkable individuals, who came so far and did so much, lie anonymously in unmarked graves such a long way from home.

Absolutely fascinating. I have loved reading your several pieces on the St Hill brothers. All of it is new to me except for the unforgettable CRL James portrait of Wilton. Thank you very much. I look forward to reading more of your pieces. Chris

LikeLike