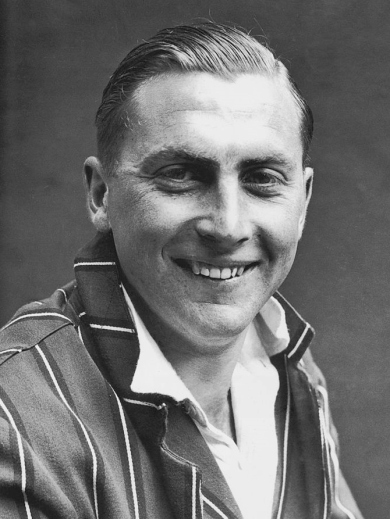

Harold Gimblett in 1936 (Image: Wikipedia)

The incredible first-class debut of Harold Gimblett, the 20-year-old son of a farmer, for Somerset in 1935 catapulted him to fame from the very start of his career. His 63-minute century against Essex was one of the most spectacular debuts by any player and suggested that a promising career was beginning. When Gimblett was forced to retire 19 years later owing to a severe mental health condition which required his admission to hospital, he had largely fulfilled that promise. Over those years, he was to prove more than useful. He became — and remains, almost seventy years after his retirement — Somerset’s leading run-scorer in first-class cricket. He was an entertainer much loved by the county’s supporters and played many great innings. And yet underneath the success, there was tension and bitterness, to which there were two contributing factors. The first was the nature of cricket in the years around the Second World War: a Somerset Committee which handled all professionals with a brutal lack of sympathy, empathy or understanding, and a sport riven by deliberate class distinction in which the amateurs were on top, and professionals were treated as menial hired hands (a distinction which was often harsher at counties like Somerset which had a greater proportion of amateurs in the team). But the second factor was Gimblett’s own lifelong struggle with mental health.

Most of what we know about this comes from Gimblett’s own account, provided in a series of tape recordings intended for the ears of David Foot, with whom he planned to collaborate on an autobiography. The project never got off the ground before Gimblett’s suicide in 1978, but Foot turned the searingly, painfully honest recordings into a 1982 biography Harold Gimblett: Tormented Genius of Cricket. There had never quite been anything like it before, owing to the fact that Gimblett did not intend his words to be published when he spoke them (but he gave permission, as did his widow after his death, for Foot to use them) and so they did not have the usual filter applied by sporting stars in writing their autobiographies. There is no parallel account of the life of a cricketer in the period around the Second World War. And yet his words find an echo in the experiences of modern players whose mental health suffers under the unrelenting pressure of professional and international sport. This can be seen most clearly in his memories of his Test debut for England in the first match of a series against India in 1936, in which he dreaded having to play. But an unbeaten, match-winning 67 in the second innings (the highest score of the game) provided him with another fairly-tale debut and meant that he retained his place. This proved something of a turning point for him.

At the time, the England selectors were looking around for new players to refresh the team and replace some veterans after a string of poor results. For the second Test, Gimblett’s opening partner was the debutant Arthur Fagg, who like him was only 21 years old. In a high-scoring game, Gimblett made just nine runs out of England’s 571 for eight declared. He also missed a catch when India batted and was dropped from the team for the third Test. While somewhat relieved to escape from the pressure, he was affected for the rest of the summer by what he perceived as his failure, which continued to weigh on his mind and impacted on his form. After his Somerset debut the previous summer, he had similarly struggled for consistency in the aftermath, but never questioned his own methods. Nor had he particularly clashed with the Somerset authorities. But something seemed to change (if we can believe his own account) now that he was an international cricketer. The Somerset Committee attempted to force him to temper his aggression, but he was not willing to compromise, even when he form had fallen away. For the rest of the season, he struggled with the hook shot, which he had always played successfully, and sought out Herbert Sutcliffe, an acknowledged expert at the shot, for technical advice. An unsympathetic Somerset Committee simply told him to stop playing the shot, which he refused to do. He also clashed with his captain after one game in which he hit a full toss for six in the last over of a day’s play; he was told that he would be dropped if he ever took such a risk again.

The result of all this was another loss of form. In his first five matches of the season, Gimblett had scored 623 runs with three centuries, at an average of 103.83. By the time of his selection for England, he had scored 1,041 runs in 12 matches at 57.83. In the remainder of the season, he managed just 605 runs at 18.91. His final record for 1936 was 1,608 first-class runs at an average of 32.81; respectable but far short of what seemed possible at the start. His temperament in big matches and his slip fielding were also questioned by Wisden, which, as it had done after his debut, counselled a more careful approach. But how much had the scrutiny of the opening weeks of the season, and the pressure — and what would probably today be termed as anxiety — before his England debut affected him? The effects lasted into the following two seasons, when Gimblett struggled to live up to the potential identified in the press. Others overtook him in the race for England places, and he seemed unsure of the best way to bat. He was heavily criticised in 1937 for his overly aggressive batting and was briefly dropped down the order. Yet he was outwardly unconcerned and stubbornly maintained his approach; sometimes he seemed overconfident and played in deliberately unorthodox fashion. Again, this is perhaps less an indication of arrogance and more a sign that all was not well. He still managed 1,500 runs that summer, at an average just over thirty, but fell away in 1938, and his average dropped to 27. Moreover, he was often unfit, battling “aches and pains”.

Gimblett at his wedding to Ria Burgess in 1938 (Image: Harold Gimblett: Tormented Genius of Cricket (1982) by David Foot)

Gimblett finally began to recover his batting skill in 1939, and made a distinct advance. Perhaps this was early a result of his previous experiences, or perhaps it arose from a change in his personal life. In December 1938, he had married Marguerita (Rita) Burgess, whom he had known for some years. They eventually had a son, Lawrence. Whatever the cause, Gimblett made an excellent start to the 1939, similar to that of 1936, and scored 905 runs in his first seven games. Such form resulted in a recall to the England team for the first Test against the West Indies team that toured during the season. Perhaps unfortunately, it was once more played at Lord’s, a ground that often made him uncomfortable owing to what he perceived as extreme snobbery and social prejudice. In the first innings, he was bowled by John Cameron for 22 when he lost sight of a flighted delivery; in the second, he hit his first two deliveries, bowled by Leslie Hylton, for four and six, as England chased a target against the clock. But in looking to score quickly, he was bowled by Manny Martindale. Unlike during his previous Test appearances, his fielding was singled out for praise in Wisden; he took one spectacular catch to dismiss Ken Weekes, for which he was congratulated by the new batter, Learie Constantine. But he had not done quite enough and was dropped for the final time, having played only three Tests for England. Although it is hard to be certain, some of his team-mates suspected in later years that, whenever there was a chance that he might come back into England selection, such as before a touring team was chosen, he deliberately batted poorly so that he would not be picked. Nevertheless, in 1939 he managed to maintain his form and finished the season with 1,922 runs at 40.89.

The outbreak of war in 1939 brought a pause in Gimblett’s career, and he found the next few years difficult. He volunteered for the Air Force, but for reasons that are not quite clear was instead allocated to the Fire Service where his duties involved dealing with the aftermath of bombing raids. Foot notes that some of Gimblett’s team-mates thought that guilt from not seeing active service affected him after the war. But he was equally affected by his experiences as a fireman, especially when some of his colleagues were killed in an air raid, and he possibly suffered depression from having to deal with the destruction. Foot had received information that “his dormitory locker was full of pills.”

When county cricket resumed, Gimblett did better than ever. Somerset were surprisingly good in 1946 and finished fourth in the County Championship; Gimblett was a key player, averaging almost fifty. More circumspect than he had been, he still was capable of powerful shots but was less reckless. He scored his first double-century when he hit 231 against Middlesex in 320 minutes (32 fours, 1 six). If there was a slightly drop-off in 1947, the team leaned almost entirely on his runs in 1948. Against Sussex that summer, he scored 310 (465 minutes, 37 fours, 2 sixes), the highest innings by a Somerset player, surpassing the 52-year-old record set by the amateur Lionel Palairet, who scored 292 in 1896. However, the Somerset Committee refused to recognise the achievement. Gimblett said: “Arthur Wellard went to see the secretary, Brigadier Lancaster. ‘Harold’s just made 300. Will you allow a collection around the ground for him?’ The answer was prompt: “He’s paid to score 300. There will be no collection.’ I think that was when I first decided my career with Somerset was going to end. I was deeply hurt.” He and his team-mates suspected that the Somerset hierarchy were displeased that a professional had beaten the record of a famous and revered amateur from the past. But that was not his only spectacular achievement in 1948: against Glamorgan, he scored 70 which included six sixes in 13 balls from Len Muncer.

Somerset in 1946, illustrated on a benefit leaflet for F. S. Lee (Image: Harold Gimblett: Tormented Genius of Cricket (1982) by David Foot)

This immediate post-war period was perhaps Gimblett’s peak as a cricketer. He was adored by the Somerset crowds and enjoyed their adulation. But this brought its own internal pressures. While he struggled with the scrutiny and expectations of playing for England, and although he did not like journalists or the press in general, he enjoyed hogging the headlines for Somerset and was sometimes jealous of team-mates who usurped the attention. He hated to fail, and team-mates described how he would throw his bat around the dressing room if he was dismissed cheaply; they knew to keep away. Nor did they criticise him, because he did not respond well; in fairness, he did not especially enjoy praise either. Yet it left him with a reputation as something of a prima donna, not least because his reactions could be unpredictable. Foot tells several stories: how he once refused a drink from a Somerset member after he scored a large century, and had to be persuaded to accept; how he angrily shouted at Lancashire members who were critical of an umpiring decision that went against their team: “Why don’t you go back to the bloody mills and do an honest day’s work”; how when he was dismissed early in an innings played at Lord’s, and an MCC member complained “I’m sorry you are out, Gimblett; I’ve come a long way to watch you bat”, he stopped and replied: “You ought to have bloody well stayed at home.”

Nor was he a particularly good team-mate. Although he got on well with the other professionals, he was not especially interested in their success. He did not usually watch them bat, and only rarely offered technical advice despite being knowledgable about such matters. And he did not always consider the interests of his team while he was batting; he sometimes played how he wanted to play rather than as the situation demanded and sometimes was prone to play deliberately poorly if he knew selectors were watching. One amateur team-mate, according to Foot, suggested that if he was hit by a short ball (although he was generally very skilled against bouncers and fast bowling), he sometimes surrendered his wicket shortly after. Nevertheless, when the mood took him, he was a good team man, getting his head down and seeing off the new ball, or battling through difficult situations when Somerset were in trouble. Yet he never wanted responsibility and captaincy held no appeal for him.

Perhaps more importantly, Gimblett rarely got along with the amateurs in the team and could be difficult for the captain to deal with, particularly at a time when Somerset had a succession of short-lived captains who struggled to establish themselves. In fact, he had a problem with authority, refusing the demands of the Somerset Committee to drop the hook shot; he lacked deference even towards figures as distinguished as Pelham Warner. As the writer (and former Somerset player) R. C. Robertson-Glasgow put it: “Someone remarked that perhaps he is too daring for the grey-beards. My own view is that he is also too daring for the majority of the black-beards, brown beards and the all-beards, who sit in judgement on batsmen; in short, too daring for those who have never known what it is to dare in cricket.” The editor of a local newspaper who went to school with Gimblett called him an “infuriating enigma”. John Daniell, a hugely influential figure at Somerset for much of Gimblett’s time there, was baffled by the opener. He was often heard muttering: “That bloody Gimblett”. The latter in turn never forgave Daniell for rejecting him as a Somerset player before he made his famous debut (when he was chosen, just as an unsuccessful two-week trial was coming to an end, largely because no-one else was available).

Off the field, Gimblett had a reputation as a hypochondriac; he complained of aches and pains and suffered from migraines. He frequently visited doctors and was known, particularly after his mental health struggles became serious, for always having bottles of painkillers in his kit. He often kept to himself and was very introverted. Yet his rebelliousness was admired by his fellow professionals, who often conformed to get ahead.

Gimblett set another record in 1949, when he reached 2,000 first-class runs in the season for the first time; his 2,063 runs was the highest in a season for Somerset (beating Frank Lee’s 2,019 runs in 1938). During another solid season in 1950, Gimblett made runs for Somerset against the touring West Indies team. As a result, when Len Hutton withdrew from the England Test side, Gimblett was chosen to replace him. However, Gimblett developed a painful carbuncle on his neck and therefore was unable (or perhaps unwilling) to play; there were suggestions that the carbuncle might have arisen through the stress of his selection.

During the 1950–51 season, a “Commonwealth XI” toured India and what was then known as Ceylon; this took place at the same time that an England team toured Australia. Gimblett was chosen in the Commonwealth team and did reasonably well on the field. But he did not enjoy the tour: “It was a bad time for me — I had no energy, no spark, no conversation. I became very withdrawn. At first I wondered whether I’d picked up a bug. But it was purely mental.” He also struggled with Indian food and climate; he lost weight and came home looking very thin. Foot concluded that “Gimblett was temperamentally unsuited to touring”. But even this might be harsh; the experience he describes sounds very similar to the accounts of more recent England players, like Jonathan Trott and Marcus Trescothick, who hated the life of a touring cricketer, which exacerbated their symptoms of anxiety.

Gimblett batting at Bristol against Gloucestershire in 1953 (Image: Harold Gimblett: Tormented Genius of Cricket (1982) by David Foot)

The after-effects of the tour lingered into the 1951 season and Gimblett took a complete break in July, after doctors told him that he was “run down”. When he returned in August, he scored three centuries. The instability of the Somerset team cannot have helped; both the captain and Gimblett’s opening partner changed with bewildering frequency in this period. During his benefit season of 1952, he scored 2,000 runs again. At the end of the season, he took his family on a six-month trip to Rhodesia after being invited there in order to coach and play a little cricket. He was tempted to stay but chose to honour his Somerset contract and, according to Foot, “the pending political mood [in Rhodesia] bothered him.” Although he scored heavily again in 1953, there were suggestions that he had stopped enjoying the game and rumours of his imminent retirement, or his need for psychiatric treatment, circulated. Although he continued to bat well, Foot suggested that he was “inclined to look an old man” even though he was only 38. Gimblett himself said: “I couldn’t take much more. I was taking sleeping pills to make me sleep and others to wake me up. By the end of 1953, the world was closing in on me. I couldn’t offer any reason why and I don’t think the medical profession knew, either. There were months of the past season that I couldn’t remember at all.”

After struggling over Christmas 1953, Gimblett was admitted to the mental hospital Tone Vale (near Taunton) and had electro-convulsant therapy twice a week. He was a patient for sixteen weeks before rejoining Somerset for the 1954 season. He struggled through pre-season and played the first game although he wanted to come off mid-innings. When he was out for 29, he returned to the dressing room and had what Foot called “a bitter little monologue”, while Gimblett said that “I wanted to get it all out of the system in one go.” There were suggestions that he was reported to the Secretary; in the next game, he scored a duck against Yorkshire and when he returned to the dressing room, said that he couldn’t take any more. He left the ground mid-game; he batted in the second innings but was told by the captain to take some time off. He never played for Somerset again; he was soon a patient at Tone Vale once more. When he returned to the county ground later in the season to sit in the scorers’ box, he was ordered to leave.

The rejection, and lack of sympathy from Somerset throughout his career, left Gimblett bitter. Although he served on the Somerset Committee in the 1960s, and was heavily involved in fund-raising, he never quite forgave the county. These feelings were doubtless exacerbated by his mental health struggles, which continued for the rest of his life. He never knew the cause because he never received a diagnosis. But his problems were by no means limited to his cricketing experiences.

At the time of his enforced retirement, Gimblett had amassed an excellent record. He had scored 23,007 first-class runs at 36.17 (and took 41 wickets at 51.80); of those, 21,142 were for Somerset and even today, almost seventy years after his retirement, he remains Somerset’s leading run-scorer in first-class cricket, just ahead of Marcus Trescothick. In among those runs, he scored fifty first-class centuries; all but one came for Somerset, but he is second to Trescothick in the list of leading century scorers for the county. His innings of 310 remains the fifth highest score for Somerset; it was surpassed by Viv Richards in 1985 (and the record-holder is currently Justin Langer with 341). In his three Test matches, he scored 129 runs at 32.25.

After leaving Somerset, Gimblett briefly played professionally for Ebbw Vale Cricket Club, having struggled to find other employment. He also began to work at a steel works in South Wales as a safety inspector. He struggled with his mental health and the job in the steel works — and the unions — and at one point drove back to Somerset alone for a day, not returning home until the night. In his second season at Ebbw Vale, he left the steel works and took a job working on a farm but his schedule left him too tired to play for the club mid-week and his contract was terminated by mutual agreement. He later took a job at R. J. O. Meyer’s Millfield School as the head coach, with half an eye on returning to play for Somerset. Meyer was supportive but the Committee did not want Gimblett to return. In any case, he worked for twenty years at Millfield, performing various roles (including running the sports shop) and playing plenty of informal cricket. When Meyer retired, Gimblett’s relationship with the school became fractious and he began to hate his job. At one point, recognising that he was struggling, he applied to another school before changing his mind. He once more was treated in a mental hospital with electro-convulsant therapy. He retired on medical advice, not least as he was struggling with various physical ailments (some of which required surgery in later years).

In his final years became more and more reclusive, and by the end of his life actively disliked cricket. Even his wife, to whom he remained close, told Foot that she never entirely understood him. In his turn, Gimblett felt that he had been unkind to her early in their relationship, and regretted it. In March 1978, Gimblett took an overdose and was discovered next morning by his wife. Foot summarised this unhappy ending: “The tragedy is that he was able to share too little of the joy and sheer pleasure he brought to the game of cricket.” But this seems too simple of a conclusion for a complicated man who clearly had endured serious mental health problems which would have been beyond the comprehension of his contemporaries, little understood by the medical establishment of the time and even when Foot was writing in 1982 remained a source of shame and stigmatisation. Perhaps in the modern world — and even in modern cricket — Gimblett might have received better treatment (in both the medical and professional sense).

We cannot do justice to such a complex issue — nor, in fairness, to a complex life — here. But perhaps we can consider his standing as a cricketer. A sympathetic obituary in Wisden, although it did not mention his cause of death, summarised his career very effectively: “People sometimes talk as if after [his debut] he was a disappointment. In fact his one set-back, apart from being overlooked by the selectors, was when in 1938, probably listening to the advice of grave critics, he attempted more cautious methods and his average dropped to 27. But can one call disappointing a man who between 1936 and his retirement in 1953 never failed to get his 1,000 runs, who in his career scored over 23,000, more than any other Somerset player, and fifty centuries, the highest 310 against Sussex at Eastbourne in 1948, and whose average for his career was over 36?”