Gilbert Laird Jessop by Albert Chevallier Tayler, after a photograph by George William Beldam

lithograph, 1905; 14 3/4 in. x 9 3/4 in. (375 mm x 248 mm); Purchased, 1987

Primary Collection NPG 5958

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Although far less revered than he once was — for example forty years ago, Ian Botham was often compared to him — Gilbert Jessop’s name has remained known largely thanks to his century at the Oval in 1902 that is still the fastest scored by an English Test batter. And countless times it has been suggested that he would have been ideally suited to modern cricket: during times when cricket was played in dour, defensive fashion, there were frequent assertions that another Jessop would have broken the shackles; when first one-day and then T20 cricket became increasingly important, those of a historical disposition were quick to point out that Jessop had been playing that kind of cricket long before it was fashionable and would doubtless have excelled in the more frenetic formats. While this kind of speculation is always interesting, it can never be definitively settled and anyone trying to prove or disprove that Jessop would have been a success had he played in 2023 is deluding themself. However, owing to Jessop’s fame and the impact he had on cricket during his career, we know an enormous amount about how he played the game.

A short summary makes it clear that Jessop would in many ways have been an ideal T20 cricketer. Aside from his batting feats, ludicrously fast scoring and ability to hit the ball to (and over) the boundary, he was an outstanding fielder and a serviceable fast bowler in his younger days. It is easy to imagine IPL franchises being desperate to secure his services. Yet he was the product of a different age: a schoolteacher turned stockbroker whose ambition to enter the Church of England was foiled by his lack of schooling. And he was an amateur who would never have countenanced professional sport; while happy enough to play alongside professionals, he had no desire to become one. Like most of his amateur contemporaries, he would have been appalled by the modern cricket world.

But in many ways, Jessop was ahead of his time in a cricketing sense; there had been hitters before him but none who even remotely approached his level of success. For example George Bonnor of Australia averaged 21 in first-class cricket and Charles Thornton averaged 19; Jessop’s average was just short of 33, which was more than acceptable for any batter in that period. Not that he would have cared, as he once wrote that “statisticians are anathema to me”. For all the risks that he took, he was extremely successful: to achieve an average over forty in an English season, as he did four times between 1900 and 1911, was extremely difficult and the mark of a quality batter. And if his style meant that he inevitably endured fallow periods (and throughout his career, his spectacular innings were often followed by a run of poor scores), when in form he could be extremely consistent. For example, he scored nine fifties in 15 innings in 1900.

Gilbert Laird Jessop (‘Men of the Day. No. 816.’) by Sir Leslie Ward

chromolithograph, published in Vanity Fair 25 July 1901

14 1/8 in. x 9 1/2 in. (359 mm x 242 mm) paper size

Reference Collection; NPG D45076

© National Portrait Gallery, London

No other top players in this period batted like Jessop; lesser cricketers, such as Ted Alletson, might achieve a one-off success through slogging, but few built a career on big hitting and none as successfully as Jessop. Even relatively fast scoring batters from later periods such as Jack Hobbs, Donald Bradman or Viv Richards — all of whom were undeniably superior to Jessop — never approached Jessop’s scoring rate, although unlike him they were capable of batting in more than one way. It has only been over the last twenty years that it has become customary for Test and first-class batters consistently to score quickly as the default tactical choice. However, even if comparisons across history could ever be meaningful, we do not have enough data to make reliably comparisons between Jessop and modern batters. All we can do is to examine how he played.

Gerald Brodribb, in The Croucher: A Biography of Gilbert Jessop (1974), looked in great detail at the statistics available for Jessop’s career. According to Brodribb: “His fifty-three centuries were scored at an average rate of 82.7 runs an hour, while his 127 scores of 50 to 99 were made at an average rate of 76.32 runs an hour. Together his 180 scores of 50 or more were scored at an average rate of 79.08 runs an hour.” His fastest fifty took just 15 minutes (something he achieved in 1904 aginst Somerset and in 1907 against Hampshire) and is fastest century came in 40 minutes against Yorkshire in 1897 (he scored a a 42-minute century for the Gentlemen of the South against the Players of the South in 1907). Fifteen of his first-class hundreds were scored in under an hour. And in 1903, he scored 200 in two hours against Sussex (and in 1905 he managed 200 in 130 minutes against Somerset). He rarely batted for a long time. In first-class cricket, he batted 855 times but according to Brodribb: “Only once did he bat for more than three hours, only ten times for more than two hours, and only thirty-five times in all did he bat for more than 90 minutes.”

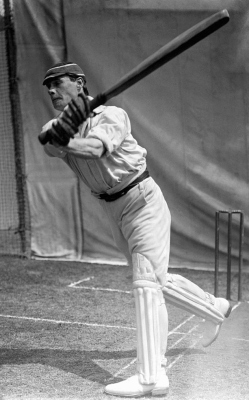

Gilbert Jessop batting (Image: Wikipedia)

He often dominated the scoring while he was at the wicket: for example, in 1901 he scored 66 out of the 66 runs added to the team score while he was batting against Sussex; in 1895, he scored 63 out of 65 against Yorkshire; in 1900, he scored 109 out of 120 against Middlesex; in 1908, he scored 75 out of 80 in the first innings against Nottinghamshire and then 78 out of 86 in the second. But such records rapidly become meaningless so often did Jessop dominate: 92 out of 106 (v Sussex in 1903); 110 out of 122 (during his 126 against Worcestershire in 1902); 171 out of 206 (for Cambridge against Yorkshire in 1899); 191 out of 234 (for the Gentlemen of the South against the Players of the South in 1907); or his highest score of all, 286 scored out of 355 against Sussex in 1903. Brodribb calculated that he made around 72 per cent of the runs scored by his team during his centuries.

For a modern audience, the only measurement of significance is the batting “strike rate” — the number of runs scored per 100 balls in an innings. The number of deliveries that Jessop faced is only known for a handful of larger innings as it was not customary to report this statistic until long after the Second World War; any evaluation of scoring rate was instead based on time at the wicket. Yet something about Jessop inspired journalists and spectators sometimes to keep track of how many deliveries he had received — something rarely done for any other player until the 1920s and 1930s. Brodribb recorded the most notable of Jessop’s innings for which we know how many balls he faced:

| Runs | Deliveries | Match | Strike Rate |

| 61 | 24 | Gloucestershire v Somerset, Bristol 1904 | 254 |

| 72 | 29 | Gloucestershire v Warwickshire, Cheltenham 1908 | 249 |

| 54 | 22 | Gloucestershire v Hampshire, Cheltenham 1913 | 245 |

| 116 | 57 | Lord Londesborough’s XI v Kent, Scarborough 1913 | 203 |

| 66 | 36 | Gloucestershire v Somerset, Bath 1906 | 183 |

| 66 | 37 | Gloucestershire v Sussex, Bristol 1901 | 179 |

| 85 | 52 | Gloucestershire v Essex, Bristol 1907 | 163 |

| 92 | 64 | Gloucestershire v Hampshire, Cheltenham 1907 | 144 |

| Test Matches | |||

| 93 | 69 | England v South Africa, Lord’s 1907 | 134 |

| 102 | 79 | England v Australia, The Oval 1902 | 130 |

Figures collated by Gerald Brodribb; their origin in usually uncertain and might not always include the delivery from which Jessop was dismissed.

Perhaps some of these innings were scored against weaker counties on smaller grounds; but until 1910, a ball had to be struck out of the ground, not just over the boundary, to be awarded six runs. A hit into the crowd — worth six today — only counted as four. Under modern rules, some of Jessop’s innings would have been quicker and larger.

Such was Jessop’s fame that his career record attracted a great deal of analysis, most notably by Gerald Brodribb. Just a couple more points will suffice. During his first-class centuries, he reached three figures in an average time of 72 minutes and scored at an average rate of 82.7 runs per hour. The only batters from before the Second World War who matched or surpassed this rate in longer innings were out-and-out hitters — such as Jim Smith or Charles Thornton — whose average was considerably lower than Jessop. By Brodribb’s calculation, the “average” rate in cricket in this period was around 30 runs per hour; he worked out that of the leading batters who played before the Second World War, Frank Woolley and Victor Trumper averaged around 55 runs per hour; Charlie Macartney and Ranjitsinhji managed around 50 runs per hour; Donald Bradman, Archie MacLaren, Denis Compton between 45 and 50. While such statistics must be treated with caution — it is unclear how Brodribb reached these figures and slower (and smaller) innings would probably have been excluded from his calculations — they give an indication of how Jessop scored atypically quickly for the period in which he played.

Perhaps more importantly was the perception that he scored quickly. Whenever he came out to bat, a ripple of excitement passed through the crowd. After his 93 against South Africa in 1907, one journalist spoke to the spectators: “‘I’d give up a day’s work to see Jessop,’ said a man with a dented bowler hat. ‘That’s what I call cricket!'” An innings by Jessop was guaranteed entertainment; he often aimed his shots at the largest buildings. His fame drew crowds of spectators and attracted headline writers and advertisers. One story might best illustrate this. Shortly after he had scored a double century for Gloucestershire, he appeared for a team representing the Daily Mail in a match against a club in Sutton. His first ball was bowled by a “gardener’s boy” who — according to Brodribb — bowled him with a shooter. The boy “yelled out a delighted ‘Hurrah!’ as he saw how he had got rid of the great man … and he proceeded to do a series of cartwheels all around the ground until such unseemliness was put an end to.” And everyone knew that the crowds came to see Jessop. On the last day of a match at the Hastings Festival in 1899, Jessop came down the pitch to a lob from Digby Jephson and missed, to be stumped. But the umpire Bob Thoms gave him not out, saying: “‘Not out … not out — sixpenny crowd — Saturday gate — can’t disappoint ’em — near thing — near thing — but not near enough for the occasion.” Jessop went on to score 68-minute century as the game rifted to a draw.

How was Jessop able to score so consistently quickly? He adopted his batting stance early in his career so that he was bent low over the bat in order to allow him to run down the pitch faster (adapting the idea from when he ran in sprint races). As a result, he was given the nickname “The Croucher”. He crouched so low that in 1904, he was given out lbw when hit on the head by the ball. But Jessop wrote in 1921: “I have had small reason to regret taking up a stance which a writer once graphically described as a position whereby the aroma of the pitch could be sampled to the best advantage.” At the same time, he also adopted an unusually low grip on the bat to allow him to switch his stroke at the last moment if the bowler saw him advancing and altered his length. His success was based on his strength, quickness of hands and feet, and depended on watching the ball very closely. Although he told his son never to premeditate a shot before the ball was delivered, he often predetermined when he would run down the pitch. A relative of his was once told a story in which a bowler saw Jessop coming and did not release the ball. According to Brodribb: “Jessop went on coming, so the bowler walked towards him. They met in the middle of the pitch, and the bowler said: ‘Eh, Gilbert, was there something you wanted to say to me, lad?'”

As well as being called “The Croucher”, Jessop acquired other names. For example, an 1897 poem by Ralph Paine, written during the tour of America by Pelham Warner’s team that included Jessop, featured the lines:

“At one end stocky Jessop frowned,

The human catapult,

Who wrecks the roofs of distant towns

When set in his assault”

C. B. Fry later borrowed the “catapult” for his description of Jessop’s 1902 innings at the Oval. Others dubbed Jessop with a different name, reflecting the educational background of many amateurs, which focussed on Classics: “Jessopus”, a name suggesting mythical heroism, and one with which Jessop often signed letters.

If Jessop was famed for fast scoring feats and big hitting, he also produced runs when they were most needed, such as on that famous occasion at the Oval. And one of his best performances came against Yorkshire at Bradford in 1900, where he benefited from the dimensions of a small ground. The home attack, which had carried all before it that season, comprised George Hirst, Wilfred Rhodes and Schofield Haigh. In reply to Yorkshire’s 409, Gloucestershire scored 269 of which Jessop scored a somewhat lucky 104 in 70 minutes (he was last man out). After bowling out Yorkshire for 187 in their second innings, Gloucestershire needed 328 to win. When Jessop came in, Gloucestershire were in some trouble at 69 for four (and 73 for five soon after). The first over that Rhodes bowled to him went for 18 runs (including two sixes out of the ground); later on, he again hit Rhodes twice out of the ground in one over. By lunch was 81 in 43 minutes, and soon after he reached his second century of the game in just 59 minutes. Having added 60 runs with Cyril Sewell, Jessop was joined by Francis Bateman-Champain, and they took Gloucestershire’s total to 233 for five when Rhodes was brought back into the attack. Jessop cut the first ball for four; the second he struck over the football stand for six; the third he left alone; the fourth he hit into the crowd (where he was caught by a spectator) for four (as it was not hit out of the ground, it did not count as six according to the pre-1910 version of the laws); the fifth went over the football stand for another six. Twenty runs had come from the first five balls, leaving Gloucestershire needing just 73 to win. Jessop drove the sixth ball high in the air, where it was caught one-handed by John Tunnicliffe, leaping on the boundary edge. He was out for 139 in 95 minutes (one observer suggested that 10 of those minutes had been spent “recovering the ball”) out of 182 runs scored. Rhodes took another two wickets to finish with six for 120 from 24.4 overs (and fourteen for 192 in the game from 45.3 overs), but he had been hit for seven sixes by Jessop (who scored 76 from the 27 deliveries Rhodes bowled to him), and in the seven overs before he had Jessop caught, he had conceded 81 runs. And under the post-1910 rules, several of his fours in the game would have counted as six: he hit as many as 20 deliveries over the boundary. But Yorkshire eventually won by 40 runs. And that season, Rhodes took 261 first-class wickets at 13.81.

Wilfred Rhodes (Image: Wikipedia)

Jessop later wrote of that season:

“I had a good deal of experience of Wilfred’s bowling in 1900, for apart from the two meetings in the County Championship, we saw something of each other in the Gentlemen v Players matches at Lord’s and Scarborough, as well as in two North v South matches, and Yorkshire v C. I. Thornton’s XI. We faced each other in fourteen innings — one of which was incompleted — and on no fewer than eight occasions I fell to Wilfred’s wiles. Small wonder, therefore, if the cricket reports of the Yorkshire evening papers should be so frequently headed: ‘Jessop again falls a victim to Rhodes.’ Still, I had no good reason to feel that I was one of Wilfred’s ‘rabbits’, for in the course of those fourteen innings I had managed to ‘pouch’ some six hundred and forty-seven runs. Luck as regards the state of the pitch was on my side, for only on three occasions did the conditions favour the bowler. No matter how much Wilfred was ‘punched’ he always came up smiling for more, and as he had supreme confidence in his fieldsmen and bowled to them with unerring accuracy, he seldom failed to reap his reward.”

Rhodes also remembered that game. Haigh had suggested that the team should bowl wide to Jessop, to make him reach for the ball, “but the wider we bowled, the harder he hit the ball, and five times he hit me from well outside the off-stump into Horton Park … After that match I said to Schof. [Haigh], ‘From now on I’m going to bowl well up and straight. Then if he misses, I’ll hit.” Rhodes suggested to one interviewer that after this, apart from when Jessop scored 233 for The Rest of England against Yorkshire in 1901, “he never put up a big score against us again”, but this is not supported by the figures as he continued to score heavily against Yorkshire for the rest of his career, although he only scored one century after 1901.

Perhaps the innings against Yorkshire at Bradford is more illustrative of Jessop’s impact than any other. Not only did he change the course of a game almost single-handedly, he disrupted the plans of probably the best bowling attack in England and forced a complete tactical rethink. And although Gloucestershire ultimately lost, all the praise in the aftermath — even in Yorkshire, despite his annihilation of the home attack — was directed at Jessop. Undoubtedly the valiant failure of a glamorous amateur was worth more in cricket at that time than the fourteen wickets by one of its leading professionals, but that is a slightly different story.

But if Jessop was revered in England, Australians were less impressed. The 1902 team had openly dismissed his batting ability before the Oval innings, and that century does not seem to have altered their opinion too much. For example, the reminiscences of the 1902 Australian captain Joe Darling, published by his son in 1970, offer little mention of Jessop; Monty Noble, another member of the 1902 side briefly listed Jessop’s innings as one of those memorable ones played on sticky wickets, but was otherwise silent on his batting (he was mentioned as a good fielder); Clem Hill’s “autobiography” published by Australian newspapers in 1933 classed him as a bowler when considering the 1902 season and praised his fielding. The reason for these reservations was revealed by Hill in another article:

“Jessop was a great hitter. He was not a success in Australia, his highest score in Tests being only 35. But in England, where the wickets are slower, he would jump out and hit the ball very hard. He should have been stumped off Saunders in this Test at Kennington Oval [in 1902] before he had made 30. He was down the pitch two yards, and did not attempt to got back until he saw that the wicketkeeper had fumbled the ball. He scrambled home just in time. Darling was a great captain, but we thought he was in error in this match. The only way Jessop could play Trumble was by jumping out and hitting him. One end of the Kennington Oval is longer than the other. Trumble was bowling from the short end, known as the pavilion end, with the result that Jessop was hitting him into the grandstand. If he had been on at the long end, and Jessop had continued making the same lusty hits, be would have been caught in the outfield.”

Much more could be said of Jessop’s batting. But for contemporaries, his fielding was just as impressive. Although he held 464 catches in 493 first-class matches, it was his ground-fielding that astonished spectators, particularly his returns which resulted in many run-outs. He was a specialist extra-cover and despite the amateur ethos that decried practice in sport, he was very analytical and worked hard to improve this part of his game. He even studied baseball in an attempt to develop his fielding technique. Perhaps he was inspired by his love of that part of the game; he once wrote that “fielding has ever been to me the most attractive feature of cricket”. And as the captain of Gloucestershire, he demanded that his side could field well, and on occasion left out batters who he did not believe to be good enough fielders. In this sense, he was considerably ahead of his time.

And Jessop was a deep thinker on the game. In 1906–07, he wrote a series of perceptive but anonymous open letters to the Athletic News 1906-07 under the name “Incognitus”, addressed to famous cricketers such as W. G. Grace or C. B. Fry (and he wrote one of these anonymous letters to himself), critiquing their games and occasionally offering criticism, such as his own determination “to hit every ball to the boundary” or his observation to F. S. Jackson that not every amateur could afford to play as often as Jackson did, as they were not “born with a golden spoon in their mouths”. Unlike other amateurs, he believed that Test matches represented the peak of cricket and he thought that they were the most exciting games to play; he disagreed with the notion that their importance detracted from the spirit or enjoyment of the game. As a captain he was positive but often unorthodox; Wisden was sometimes critical of his alterations to his batting order or his habit of choosing to field after winning the toss. But he was always willing to bowl at moments of greatest pressure and was at the forefront in fielding. And he received a great deal of credit for leading a side which, other than him, often lacked quality.

Jessop was keen to make cricket as attractive as possible for spectators, and disliked the number of draws in county cricket; among his solutions were wider wickets, earlier starts, the abolition of tea intervals, and fewer flat pitches. He was also keen that games should begin on Saturdays to guarantee play for spectators at the weekend (county games — which were scheduled for three days — were usually played Monday–Wednesday and Thursday–Saturday). After experiments in 1912 and 1913, and after the First World War, Saturday starts became standard. Among his other ideas were the standardisation of rules for Tests (which were different in England and Australia), the removal of restrictions around the declaration, the less frequent publication of batting/bowling averages in newspapers, the pooling and sharing of gate money for home and away matches between two counties, and the abolition of the toss. He also favoured paying professionals more, particularly those with more experience. He also favoured the introduction of a knock-out “cup” for counties.

Some of these ideas emerged after his career had ended. If his fame meant that he continued to attract press and public attention, he had little influence with administrators. In fact, he developed a reputation as a “reformer” which did not always go down well with establishment figures. Instead, they preferred to remember him as one of the most unique and destructive batters of all time. For all the changes to cricket since Jessop’s day, that reputation remains in place. If we cannot really compare him to modern players, it is clear that he was such an outlier that he stands out as exceptional. Perhaps he was ahead of his time in how he approached cricket, perhaps not; but the amount of discussion, analysis and excitement that his batting generated among press, opponents and spectators was certainly a sign of things to come.