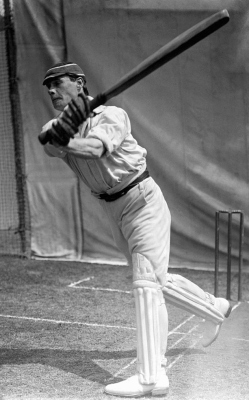

Harold Gimblett in 1936 (Image: Wikipedia)

It was the absolute exemplar of a fairy tale debut. Harold Gimblett was a man coming to the end of an unsuccessful two-week trial, in whom his captain had no faith, when he was picked to play for Somerset against Essex in May 1935. He played largely because no-one else was available and the publishers of the printed scorecards available at all games at this time did not even know his initials. He came to the wicket at number eight, when the scorecard read 106 for six. Just over an hour later, he reached one of the most spectacular debut centuries in the history of first-class cricket. Perhaps inevitably, the rest of Gimblett’s playing career, as successful as it undoubtedly was (and Foot, in 1982, called Gimblett the “greatest batsman Somerset have ever produced”), never quite lived up to that debut; sport is full of similar stories of spectacular beginnings that peter out. But in Gimblett’s case, the reasons are far from typical and the course of his cricketing life provides one of the earliest-documented cases of the devastating effect that cricket can have on mental health.

Gimblett’s story was once well-known, and was told astonishingly well by David Foot in his 1982 biography Harold Gimblett: Tormented Genius of Cricket. The book was enormously influential and became the standard work on Gimblett. The main reason for this — other than some excellent, and unusually restrained, writing from Foot — was that it was based on extensive tape recordings made by Gimblett before his death in 1978, which were intended to form the basis of a book which he hoped to write about his life with Foot’s help. Searingly and painfully honest, and never sanitised or polished for his final audience, Gimblett’s words — frequently given in full by Foot — give an almost unique insight into the thoughts of a professional cricketer in the 1930s. Of course, the usual caveats apply, not least that Gimblett was discussing events from forty years previously and his recollections were doubtless skewed by his mental health struggles during his playing days. But even so, it is a unique book and no biography/autobiography about a pre-war cricketer really compares to it for its honesty. As John Arlott wrote in his foreword, “There has never been a cricket book quite like this”.

However, the format has become more familiar since Tormented Genius was published; many recent cricketers have opened up about their own struggles after another Somerset opener, Marcus Trescothick, wrote Coming Back to Me (2008), an autobiography described by Gideon Haigh as “seminal”, about the mental health problems that ended his own career. Even before that, Ken Barrington wrote a little-remembered book called Playing It Straight (1968) which revealed his own problems with mental health that prompted him to take a break from the game in 1966 because he felt “on the brink of a nervous breakdown”. But Barrington was clearly uncomfortable discussing such matters in print: apologetic, even defensive, and concerned with what his audience might think. Modern autobiographies suffer from similar guardedness, a sense of “what will they think?” But Gimblett largely speaking for Foot, not for the reading public, so that caution is replaced with complete honesty. Even if we cannot be certain that everything he said was factually accurate — or even, at times, fair — we are reading Gimblett’s unvarnished thoughts and opinions.

Our starting point really should be that amazing first-class debut, but this requires a little background. Harold Gimblett was born in 1914 at Blakes’ Farm, Bicknoller, Somerset. He was the youngest son of Percy and Louise Gimblett. His father was a farmer, making his family relatively prosperous; he and his two older brothers attended West Buckland school in North Devon. He quickly made his name as a cricketer, and was part of the school’s First Eleven by the age of 13. In one early game, he recalled the thrill of facing the opposition’s “demon” fast bowler when batting at number nine. His batting won the game and he later recalled it as one of his proudest achievements. He was always adventurous with the bat; he remembered hitting his first ball in an organised game of cricket for six; playing for West Buckland Second Eleven at the age of twelve, he once ran seven after hitting the ball into a patch of nettles but was out trying to improvise another shot into the same nettles. But he was highly effective at school level; Foot described him as “occasionally reckless, usually dominant”. Yet off the field, he struggled with homesickness and struggled to mix with his fellow pupils. He was reluctantly appointed the team captain at the age of fifteen; worried by the prospect of leading older boys, he initially tried to back out of the appointment.

Leaving school in 1931, he initially went to London to work in the grocery trade but soon returned to Somerset and worked on the family farm. He played plenty of club cricket, usually successfully, and rattled up several big scores. Playing for the Somerset Stragglers in 1932, he scored 142 in 75 mins against Wellington School from number six, his first ever century. The following season, he scored 150 in 80 minutes against the Stragglers, playing for Watchet. He played an increasing amount of cricket for Watchet, batting in a very carefree style that meant he would alter his approach — shutting up shop and defending, or throwing away his wicket — on a whim. But the number of runs he scored attracted attention from the press.

A local tailor called W. G. Penny thought that Gimblett was good enough to play for Somerset and encouraged him in this direction despite a palpable lack of enthusiasm from the man himself. He had to be cajoled into playing in the annual match between a Somerset XI and a team selected by Penny, but he made an impression in one such match by striking the former England bowler and ex-Somerset captain Jack White for three sixes. Somerset thought he was too risky a player, or not quite good enough. But Penny persisted and Gimblett was offered two-week trial as a professional in May 1935. As was typical in the Somerset team in this period, he was simply shown his place in the changing room and told to keep to himself. He did not excel in the nets and was told he was not good enough; the Somerset secretary John Daniell told him he would be paid for the first week and then let go. Gimblett latter claimed that had enjoyed the experience, but wasn’t too disappointed (although Foot believed that the actual event was more fraught and argumentative than Gimblett recalled in the 1970s). He performed some twelfth-man duties in one match, although he did not travel with the team to an away game.

But a late injury to Laurie Hawkins before Somerset played Essex at Frome on 18 May meant that a replacement could not be secured at short notice and so Gimblett was asked to play. The ground was in a somewhat rural location, making it hard for Gimblett to reach. He arranged a lift with a team-mate but missed his bus and had to hitch to the agreed rendezvous. When he arrived at the ground, he was very nervous; when he was advised that the Essex bowler Peter Smith would bowl him a googly early in his innings, he did not know what a googly was because he had never seen one. Or so he later claimed. Somerset won the toss, batted and crumbled to 106 for six shortly after lunch. The damage had been done by the pace bowling of Maurice Nichols. Gimblett came in, using the spare bat of Arthur Wellard (his own had looked dirty enough that Wellard suggested that he borrow his), who was already in the middle. Smith bowled him a googly third ball, but he took a single without reading it; the next over, he hit Smith for fifteen runs, including a six over mid-off.

Arthur Wellard (left) and Gimblett walking to the wicket in August 1935 (Image: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 9 August 1935)

And with that, Gimblett began to score quickly. He and Wellard added 69 in nine overs, of which Wellard hit 48. He brought up his fifty with a six (28 minutes, 33 deliveries) and even after two quick wickets fell, Gimblett continued to hit, driving, sweeping and hooking. Assisted by a short boundary, his score mounted rapidly; a hook for four off Nichols was followed by a two. Although the primitive scoreboard did not include the individual scores of batters, spectators told him that he had reached an almost unbelievable century. It had taken 63 minutes and come out of 130 runs scored; it was the fastest century of the season, for which Gimblett was awarded the Walter Lawrence Trophy in September. He was eventually dismissed for 123 (79 minutes, 17 fours, 3 sixes); Somerset reached a total of 337 and, on the third day, won by an innings.

Although many batters had previously scored a century on their first-class debut — The Cricketer suggested that 22 men had done so in county cricket since 1868 — few had done so in such spectacular fashion; The Cricketer noted that the circumstances in which Gimblett batted, and the pace at which he scored, meant that he had “surely outdone all previous century debutants”. Inevitably, the press were enthralled and suddenly began to pay a huge amount of attention to Gimblett. His emergence from no-where, and his family background were a gift to newspapers. The Daily Mirror, for example, reported his debut under the headline “Farm Boy Surprises Cricket!” It also featured a photograph of Gimblett at work on his father’s farm on the first page of the newspaper.

Jack Hobbs, one of the press by then, wrote that an innings such as that played by Gimblett brought enormous pressure. And it quickly took its toll. In his next match, played at Lord’s, Gimblett scored fifty in the second innings, but had to use a runner and missed a month of cricket; and there were few runs after that. He struggled to mix with the other professionals and disliked the snobbery he saw in the game; he particularly disliked many of the amateur players. Although his trial was extended and he played regularly for the rest of the season, he scored just one more fifty and his final record — 482 first-class runs at an average of 17.21 — was quite a come-down from the fairy-tale of his debut. Wisden acknowledged his loss of form, and concluded: “Almost entirely a forward player, he appeared to pay little heed to defence, and in the end lack of experience contributed to his undoing. Still, shrewd observers maintain that he possesses distinct possibilities, and with further opportunities he may become more than a useful member of the side.”

Gimblett photographed working on his father’s farm a few days after his first-class debut (Image: Daily Mirror, 20 May 1935)

Despite his collapse in form in 1935, Gimblett had done enough to persuade the committee that he had a future at Somerset, and he signed a professional contract at the end of the season (which was worth £300 if he appeared in every match). But even if he had been uncertain whether he wanted to pursue career in cricket, his hand was somewhat forced by the death of his father, shortly before the 1936 season. His family took over the running of the farm, but the financial pressure was eased considerably if Gimblett could be “cut loose” by supporting himself through his new cricket career. Although he was a regular in the Somerset team until after the Second World War, it was not always a smooth road.

Looking back forty years later, Gimblett — without saying so explicitly — clearly identified signs in 1936 that all was not well. He began the season in spectacular form. He was promoted to open the batting — a position he held for the rest of his career — and in the opening game of the season, when Somerset played the touring Indian team, he scored a century. In the following game, he hit 93 and 160 not out against Lancashire; in the next, he scored a century before lunch on the second morning (after the first day had been washed out) against Northamptonshire, when he hit six sixes and nine fours. This rich vein of form catapulted him back into the newspapers and made him famous all over again. Almost inevitably, he came into contention for a place in the England team for the Test series against India. After a poor run of results, the Test selectors wanted to freshen up the team and replace some veterans; after his famous debut and such a good start to the season, Gimblett seemed the ideal candidate. And when the selectors went to watch him, they saw his century before lunch at Northamptonshire.

Gimblett batting during his excellent start to the 1936 season

In the tapes he recorded for David Foot, Gimblett remembered listening to the announcement of the Test side on the radio, but there was no excitement or anticipation: “I prayed that I wouldn’t be included. Far from throwing my hat in the air, I was terrified. Suddenly I realised the fearful responsibilities resting on my shoulders. The telephone started ringing, cars arrived, the usual nonsense. I just wanted to go away and get lost. I didn’t want to play for England.” Nor did it get any easier when he arrived at Lord’s, where the first test was to be played. He never liked Lord’s throughout his career, feeling it to be a place of prejudice and snobbery. When he looked outside before the match began, he was overwhelmed by the sight of 30,000 spectators waiting for the start of play; he had to be reassured and distracted by his teammates, the Yorkshire players Hedley Verity and Maurice Leyland.

Gimblett’s experience of being selected bears quite a few similarities to the experiences of modern players who faced mental health problems during their careers. In a 2020 interview, Jonathan Trott described what happened before one Test in 2013: “I knew I was in a little bit of trouble, not wanting to play. That’s when the whole anxiety of putting the tracksuit on and going to the ground was triggered.” Trott in particular struggled with the scrutiny of playing at the top level by the end of his career. This sounds very similar to the experiences described by Gimblett. In the same feature, Marcus Trescothick described what happened to him in 2006: “I had no idea what was going on at that point. I had all these feelings and emotions — not sleeping, not eating, not really being able to enjoy life or cope with what was going on. That was when it went completely pear-shaped. I knew then I was in a world of trouble. I didn’t know how to cope with or understand it. It was anxiety more than anything — I have always suffered more with anxiety than depression. There was a constant feeling of alertness, adrenaline, being worried about what was going on and how I was feeling. A panic.” And the footballer Michael Carrick spoke about not wanting to be picked for England after his experiences in 2010: “I was depressed at times, yes. I told the FA, ‘Look, please don’t pick me’.”

But in 1936, there was far less understanding than there might be today. Although Verity and Leyland might have sensed something, and tried to take care of Gimblett, the authorities would prove less understanding. But in the short term, it looked as if Gimblett had made a great success of his debut. In a low-scoring, rain-affected game, batters on both teams struggled. Gimblett scored 11 in the first innings, finding it hard to cope with the swing bowling of Amar Singh, who took six for 35. India actually took a narrow first-innings lead, but when they were bowled out for 93 early on the third and final morning, England needed 107 to win, which could have been tricky. Gimblett had spoken to Jack Hobbs after his first innings and received some technical tips, and the results were immediate. Having lost his opening partner, Arthur Mitchell, without a run on the board, Gimblett hit an unbeaten 67 in 100 minutes, the highest score of the game and one of only two fifties, including four successive fours from the pace-bowling of Mohammad Nissar. He had made a shaky start; but Wisden recorded: “As Gimblett got the pace of the wicket, however, he developed sound hitting powers and hooked superbly … The conditions during the last innings certainly favoured the batting side but Gimblett, who hit eleven 4s, played with much skill and nerve on his debut in Test cricket.” England won by nine wickets and Gimblett was once again the successful debutant. The Times called it “a glorious innings” and suggested he was a certain selection for the rest of the summer and beyond.

But Gimblett played just one more Test that summer, and only two more in the remainder of his career. While part of the reason was doubtless because his attacking style and refusal to play with more restraint concerned the England selectors, Gimblett’s story is far more complicated than that. In later years, many of his team-mates believed, he actively tried to prevent his own selection. And despite a very successful career that lasted until 1954, Gimblett never quite lived up to either his first-class or his Test debut. His cricket, like his life away from the sport, became a battle that he eventually lost…