A. E. R. Gilligan leading the England team onto the field during the fourth Test match at Melbourne during the 1924–25 series. Left to right: M. W. Tate, E. H. Hendren, A. E. R. Gilligan, H. Sutcliffe, H. Strudwick, W. W. Whysall, J. W. Hearne, A. P. F. Chapman and F. E. Woolley (Image: Wikipedia)

Arthur Gilligan was appointed captain of the MCC team in Australia in 1924–25 (England teams overseas in this period played under the name and colours of the MCC except in Test matches) for several reasons: his social background, his experience of captaining Sussex and his status as one of the best fast bowlers in England. But his selection did not meet with universal approval as there had been questions over how he led England against South Africa in 1924, and there was a better candidate in the inspirational and tactically astute Percy Fender of Surrey. Even the selectors were not quite convinced, offering the captaincy at the last minute to Frank Mann, who was unable to accept. A final setback to England’s prospects was an injury to Gilligan which severely limited his impact as a bowler, instantly removing one of the biggest attractions for his captaincy. History records that Gilligan’s leadership was unsuccessful as England lost the series 4–1; it is much harder to find judgements on how well he did as captain. But perhaps more interesting than anything which took place on the field was what Gilligan did when he was not playing.

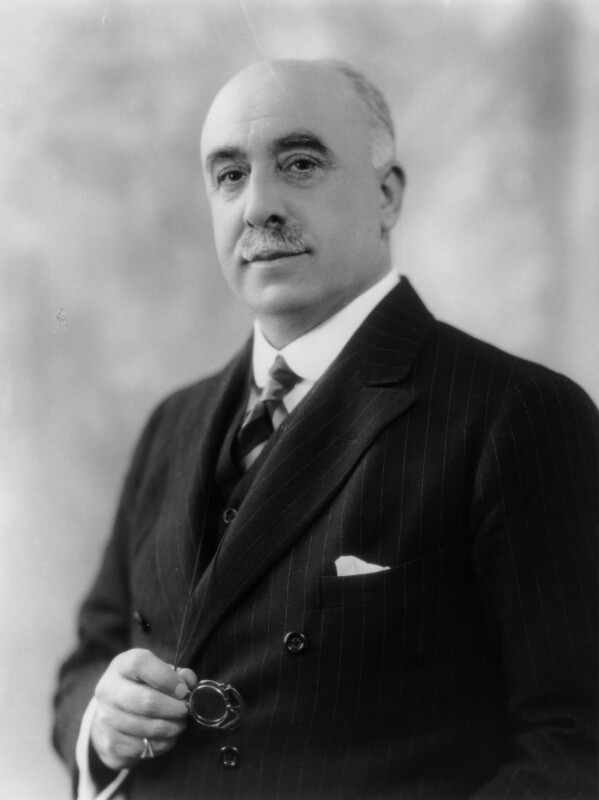

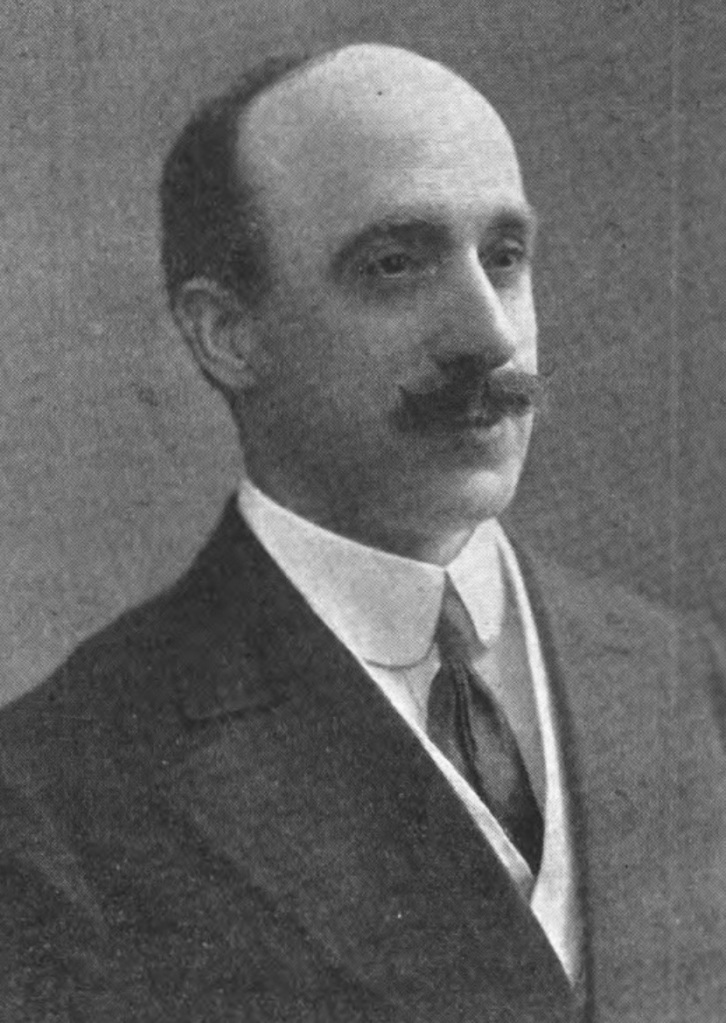

Although Gilligan was in charge of the English team on the field, much of the responsibility for what took place off it fell to the team manager, Frederick Toone, who had also held that position during the previous tour of Australia in 1920–21. Toone was the Yorkshire secretary and a capable administrator who kept the tour running smoothly and excelled in organisational matters. But he and Gilligan shared a secret; both men were members of the group known as the British Fascists.

It should be said that the British Fascists were never a major force in England, and were generally little more than an anti-communist organisation partially inspired by Mussolini in Italy. Their outlook was right-wing and traditional; their members included people from the aristocracy, high-ranking officers in the armed forces and at least one other cricketer — the Middlesex bowler F. J. Durston. There is little to indicate at this stage that they professed too many views which fascism later came to embody. Newspapers cheerfully reported on them with no hint that they posed any danger; one such report in the Gloucestershire Echo in December 1924 encouraged people to attend the “attraction of the season”, a fascist whist drive at Gloucester Town Hall. But there were occasional hints of trouble, such as a clearly anti-Communist parade by the Cenotaph in London that November, at which the leader of the movement, Major-General R. D. B. Blakeney claimed that the British Fascists simply aimed to “fight sedition and work for King and country.”

One of the early leaders made an explicit link with the Boy Scouts movement — upholding the “lofty ideals of brotherhood, service and duty”. The historian Martin Pugh, in a study of British fascism between the two world wars, writes that: “Historians have found it hard to take seriously the ‘British Fascisti’, as the organisation was initially known, regarding it as a movement for Boy Scouts who had never grown up.” Pugh suggests that “Many members undoubtedly joined in the hope of finding something mildly adventurous, but had only a superficial grasp of its politics”.

Gilligan (left) and Toone (right) holding commemorative plates presented to them in Sydney on behalf of the MCC team for their sportsmanship during the 1924–25 tour (Image: Sydney Mail, 4 March 1925)

Even so, there was some disquiet over the notion of fascism, and for the MCC it would have been undesirable for it to be widely known that their captain and manager were both members of a political organisation that, to say the least, was unorthodox and militaristic. Although neither man publicly acknowledged their membership before the tour, it is hard to believe that senior members of the MCC would not have known. And in any case, even their friends might have spluttered into their gin-and-tonics had they known what Gilligan and Toone planned in Australia.

Most of what we know of Gilligan and Toone’s activities was presented in a 1991 article in Sporting Traditions by Andrew Moore of the University of West Sydney. While in Australia, Gilligan and Toone came to the attention of the Commonwealth Investigative Branch, who had been informed by intelligence agencies in London that both men were members of the British Fascists. Although Moore cites a report written after the completion of the tour, there is strong circumstantial evidence that Gilligan and Toone arrived as fully fledged fascists with a plan to disseminate fascist literature and create local branches of their organisation. According to Moore:

“Shortly after the departure of the MCC cricketers, officers of the Commonwealth Investigation Branch became aware that an Australian legion of the British Fascists had been established in several of the capital cities. In Sydney, for instance, enrolment forms, internal memoranda and propaganda were uncovered. These were all printed in London, the contact address on the enrolment form being altered in hand-writing to a GPO Box Number…”

Moore notes that the British Fascists’ “Recruiting and Propaganda Department” instructed all members to “talk about the movement to everyone you meet” and “llways carry at least one enrolment form and one of each of the other pamphlets with you wherever you go.” The obvious conclusion — and one almost certainly formed by the original investigators — is that Gilligan and Toone brought the forms into Australia and were involved in the initial establishment of Australian fascist groups affiliated to the British Fascists. And subsequent inquiries were unable to uncover precisely how the groups had come into existence, despite the best efforts of the Commonwealth Investigation Branch and at least one journalist.

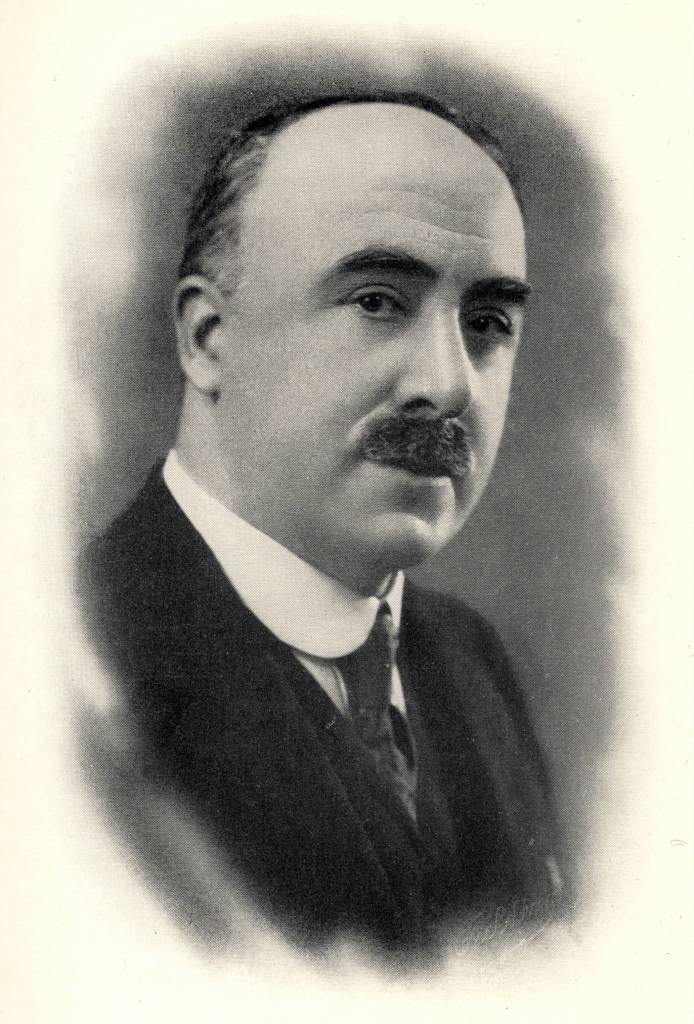

Monty Noble pictured in 1932 (Image: Wikipedia)

Although it is likely that much of the organisation was done by the disciplined and efficient Toone, it is hard to imagine that the MCC could have approved of their captain undertaking such activities while representing their club, and being the face of English cricket. The irony is that part of the appeal of Gilligan in Australia was that his uncomplicated character and apparent friendliness made him the ideal person to reinforce the imperial bonds which were such a strong part of British (and English cricket) culture at the time.

Because there is no doubt the Gilligan was extremely popular in Australia. Monty Noble, a former Australian captain who by then was a journalist, was not an easy man to please. But he was oddly enthusiastic about Gilligan in his book about the series, Gilligan’s Men (1925). He wrote that Gilligan was “the type of man who, in the most unostentatious way, can do more than all the politicians and statesmen to cement the relations between the Homeland and the Dominions.” Noble praised his sportsmanship, “cheery optimism” and “debonair countenance”.

Noble also thought that Gilligan was perfect in the role of “empire building”. There is some irony in one judgement: “In these days of national unsettlement and disruptive influences generally, Gilligan proved himself a splendid ambassador for his country. He typified the Englishman at his best, dignified, discreet, cautious, charming and optimistic in the face of all kinds of difficulties.” And in this period, an MCC captain abroad had to be involved in endless rounds of speeches, which required diplomacy and delicacy of touch. Noble praised this side of Gilligan’s captaincy: “His natural qualifications socially, his tactful speeches, and the soundness of his administration [in reality, this side of affairs was the responsibility of Toone] won more adherents to the Empire’s cause than the winning of a hundred test matches could have done.” There is no doubt that these considerations were part of the reason that the MCC had appointed Gilligan and overlooked Percy Fender, whom the establishment did not trust. Yet if their chosen man Gilligan could breeze through Australia and charm everyone, it was his sideline in promoting fascism which should have rung alarm bells at Lord’s, not Fender’s insistence that amateurs and professionals enter the field through the same gate.

The MCC team which toured Australia in 1924–25, attending a mayoral reception in Melbourne. Back row: J. W. Hearne, R. Kilner, H. Howell, R. K. Tyldesley, M. W. Tate, W. W. Whysall, A. Sandham, H. Sutcliffe, E. H. Hendren, H. Strudwick. Front row: A. P. Freeman, J. B. Hobbs, J. W. H. T. Douglas, A. E. R. Gilligan, William Brunton (Mayor of Melbourne), F. C. Toone, F. E. Woolley, A. P. F. Chapman, J. L. Bryan

For all of Noble’s attempts to champion Gilligan, the latter’s primary goal as England captain was success on the pitch. Once we set aside imperial propaganda, Gilligan’s achievements were thin on the ground. But there remained a sense that he had done well, even though England lost the series 4–1. As late as 1979, Alan Gibson wrote in The Cricket Captains of England: “[Gilligan’s] tour was successful in everything but victory, and this was sensed by the English public, who assembled in large numbers to welcome the side home … He revolutionised the English fielding, a department in which they began to compare with Australia, for the first time since the war and possibly since the early 1900s. This had much effect on the England sides of the next few years. He was, and is, one of the most popular captains England have sent to Australia.” Gibson was being a little generous; one Australian newspaper estimated that England dropped 21 catches in the series.

The mainstream view was that reported in Wisden:

“There was never great probability that Gilligan, after the injury he had sustained in the previous summer, would prove effective in the long drawn-out battles into which Test matches in Australia resolve themselves, and, as things went, he accomplished little as bowler or batsman. For all that Gilligan proved himself a popular captain and set his men a brilliant example in fielding. How highly his efforts were appreciated in this country was shown in the welcome which awaited him on his return. Had he brought the Ashes with him he could scarcely have been received with more enthusiasm.”

In reality, Gilligan’s ineffectiveness with the ball placed a huge burden on a bowling attack which lacked depth. But most official sources of information are quiet on how the captain performed in any non-diplomatic role. Was he a good captain? How did his tactics influence the result?

Neither Wisden nor The Cricketer had much to say; nor did most newspapers. But several articles written after the tour are clearly addressing complaints that had been made about the captaincy, and it seems that Gilligan did not distinguish himself tactically. His biggest critic was once again Cecil Parkin, who writing from England in the Weekly Dispatch, argued that the captain should be replaced by either Jack Hobbs or Percy Chapman. In fairness to Parkin, this did not match his complaints from 1924; his point was more the excellence of Hobbs than the ineffectiveness of Gilligan; he did, however, drop the latter from his proposed team for the third Test. But Parkin had once again grabbed the headlines, particularly through his revolutionary suggestion that a professional should be captain. This brought condemnation upon him — not least from Lord Hawke, who was provoked into his infamous “Pray God no professional shall ever captain England” speech in January 1925 — and had the effect of shielding Gilligan from other criticism; no-one in the establishment wanted to be seen to agree with the loathsome Parkin.

Lost tosses in four of the Tests — all of which Australia won — and some bad luck with injuries ultimately doomed England to a 4–1 loss. But the diminishing margins of victory in the first three matches and a dominant win by Gilligan’s team in the fourth led to a general view that the result flattered Australia; it was argued that 3–2 would better have reflected the standing of the two teams. However, that overlooked how reliant the team was on three players: Tate bowled the equivalent of 421 six-ball overs in five Tests (eight balls per over were bowled in the series), taking 38 wickets at an average of 23.18; Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe shared four century opening partnerships, including one in which they batted throughout a whole day and put on 283.

Despite this imbalance in the team, one criticism levelled at Gilligan by Noble in Gilligan’s Men was that there were too many players and therefore Gilligan was not able to give them enough time on the field to keep them in form. This is borne out to some extent by the experience of Roy Kilner, who was overlooked in the early part of the tour and did not play enough to force his way into the team until the third Test, when he immediately established himself as the best bowler after Tate. And Douglas and Howell, the supposed back-up pace bowlers, played one Test between them. But the lack of support for Tate in particular was a huge problem, exacerbated by Gilligan’s lack of impact with the ball. Throughout the series, despite having “too many” players, the English team struggled to bowl sides out cheaply.

Another incident — which Noble intended to use to illustrate a positive point about Gilligan — may have been frowned upon by those in England and in the MCC who believed that, for national prestige, England needed to win rather more than they needed to be good sports. With his team heading for defeat against Victoria in a match before the Test series began, Gilligan refused to attempt closing the game down through defensive tactics or time-wasting in the last five minutes, and the MCC duly conceded a doubtless morale-sapping defeat. Noble might have written that the team smiled and conducted themselves very well, but it was still a loss; international cricket had moved beyond sporting gestures and such an approach by the captain was something of a throwback.

Later on in his book, Noble stated:

“At the outset of the tour [Gilligan] could not have been described as a Napoleon of Cricket. But that was due wholly to inexperience … As captain, however, his improvement during the tour was astonishing. By the time the last Test was played he had learned many valuable lessons, and no experience was lost on him. His ability to use the correct bowlers for certain situations and for different batsmen increased with every match, and his placing of the field became so expert that it materially strengthened the attack, saved many runs, and steadied the rate of scoring.”

The problem, as Noble was doubtless aware, was that Gilligan had been the captain of Sussex since 1922 and had led England during the previous summer. Therefore, he should not have been making elementary mistakes early in the tour which might well have cost England dearly. Gibson, who noted without elaboration that “there were those who suggested that Gilligan was too easygoing on the finer points of law,” also mentioned how Gilligan — who was a capable batsman even at Test level — had been not out overnight at the climax of the third Test. England needed 27 to win with two wickets left, and Gilligan latest said that he had struggled to sleep; he was dismissed early on the last morning and his side lost by 11 runs. Gibson wrote: “I wonder if a harder man … might have slept better and got the runs.”

Some Australian critics thought Gilligan did a reasonable job though. Edgar Mayne, the captain of Victoria, wrote approvingly of how Gilligan spotted during the second Test that conditions would favour Hearne’s wrist-spin, and how he used Douglas to give Tate a rest. An article in the Brisbane Daily Mail defended Gilligan after some nameless authorities had blamed him for defeat in the second Test; while conceding that he was not a great captain, the writer even blamed others in the team, whom Gilligan was apparently consulting too often.

His own men were perhaps less convinced. Frank Woolley, a key member of the team, later told his biographer Ian Peebles that he believed England would have won the third Test “under a sterner captain than the genial, amenable Arthur Gilligan”. He told a story how England had been on top at one point, with two well-set English batsmen facing a tiring Australian attack when there was an interruption for a light rain shower. The Australian captain Herbie Collins went with Gilligan and the umpires to inspect the pitch. “Despite the almost non-existent effect of the rain he immediately turned to the umpires and said he thought it would be fit in an hour’s time. They nodded agreement, and Collins, moving off as though all was settled, said, ‘Suit you, Arthur?’ Arthur’s acquiescence meant rest and recovery for the bowlers and loss of touch for the batsman, all of which Frank believes could just have tipped the scale.”

But the English press would hear no wrong. At the beginning of January, even before Parkin’s article appeared, the Daily Mirror published an odd extract from what appears to be a telegram from Australia, discussing reaction there to Gilligan’s captaincy, which said: “[Gilligan’s] selection of the Test team was universally approved, his leadership very sound, and that he is largely responsible for the reputation our men have gained of being the best fielding team that has ever visited Australia.” The message concluded that even Noble or Warwick Armstrong, two of the more revered Australian captains, could have done no better. This was printed after England had conceded a score of 600, the highest in Tests until then, in the second Test.

In January, at the height of the Parkin-created storm over the captaincy, when everyone from Hawke to Pelham Warner came out to defend Gilligan, a letter-writer to the Birmingham Daily Gazette noted that it seemed forbidden to criticise Gilligan, who he argued could not be as ideal a captain as the establishment made out given that England were losing. A similar view was expressed in the Yorkshire Post soon after.

At the end of the tour, an article in the Aberdeen Press and Journal summarised the criticisms of Gilligan which other newspapers overlooked. Its biggest complaint was the he had not picked Kilner until the third Test, which left Tate overworked. And it also suggested that Gilligan should not have taken the new ball himself as his bowling merely served to play the batsmen in. A final issue was his repeated changing of the batting order, such as when he used two nightwatchmen in the third Test and opened with neither Hobbs nor Sutcliffe but W. W. Whysall.

Arthur Gilligan in 1930 (Image: Wikipedia)

Some of these issues were raised in a length interview that Gilligan gave to The Cricketer on his return to England. The gushing feature — possibly written by the editor Pelham Warner, who had contributed an article at the height of the Parkin row in which he disparagingly dismissed the idea that a professional could be a good captain — began:

“A. E. R. Gilligan, looking extraordinarily bronzed and fit, is back again in England, without having accomplished his great ambition of bringing back the ‘Ashes,’ but having brought back everything else. No more popular captain ever visited Australia, and though victory did not come his way, yet both he and his men played the game in a spirit which has endeared them for all time to the Australian public. Their reception, both on and off the field, was extraordinarily cordial, even affectionate, and when they returned home they met with a reception at Victoria Station that equalled, if it did not surpass, anything which they experienced in Australia.”

Less convincingly, the author suggested that the positive reception showed that “victory is not necessarily the main objective.” In fact, the feature is over-the-top in its praise of Gilligan and his jovial personality.

In the interview, Gilligan suggested that Australia’s more consistent batting — and the runs contributed by their tail — was the main difference between the teams, although he agreed that Tate had no-one to support him in the same way, for example, that Charles Kelleway could help Jack Gregory and Arthur Mailey simply by keeping a good length. But he made some interesting points about Collins, “a very able captain who leaves nothing to chance and who misses few, if any, points in the game.” He noted that Collins’ field-placing was extremely good and suggested that partly this was because of the scoring charts provided to him by the Australian scorer, Bill Ferguson; these early versions of the “wagon wheel” enabled Collins to work out the best field for each batter. Gilligan recommended a similar approach for the next time Australia toured England, and he was in favour of any “scientific” method which might help England in future.

Gilligan told The Cricketer that he had come to wish that he had played Kilner in the first two Tests but insisted that his form in the early part of the tour meant that others were ahead of him. Of his own bowling, Gilligan reported that he could move the new ball for a couple of overs but after that was powerless on the Australian pitches and bowling “did not greatly appeal to him”.

Gilligan also addressed some particular criticisms which had been made of his tactics in the second Test: promoting Woolley to number three ahead of Jack Hearne after Hobbs and Sutcliffe had scored 283 for the first wicket (he hoped Woolley would deal with Mailey, who was bowling, but he was dismissed for 0 by Gregory, precipitating a collapse) and why he switched the end from which Tate was bowling after he had reduced Australia to 27 for three in their second innings, after which they recovered to score 250 (Tate had been bowling into the wind and requested to switch; Gilligan said he always gave Tate what he wanted, but why would Tate not have asked for this at the start?).

Despite the nebulous nature of much of the discussion surrounding Gilligan’s captaincy, it seems clear that a better leader might have had a better result; many critics agreed it was a strong England team. And some of Gilligan’s decisions look to have contributed to the defeat. Certainly, the selectors were in future more discerning in their choice of captain and it was not longer enough just to be sporting and graceful in defeat; on the next Ashes tour in 1928–29, the apparently cheery and popular Percy Chapman ruthlessly ground Australia into submission by a policy of attrition that Gilligan would have scorned.

In fairness, Gilligan did later prove to have an analytical mind concerning cricket. Apart from his interest in Ferguson’s scoring charts, he championed using what today would be called the strike-rate of a bowler to determine their effectiveness. And his writings on future series, such as his book on the 1926 Ashes, Collins’ Men, were hardly superficial. In later years, he became a journalist and one of the earliest radio commentators after the Second World War. But as a captain in 1924–25, he was lacking.

However, his interview with The Cricketer — as well as other, shorter interviews with other publications — was not his final word on the tour. As he returned home, it became public knowledge that Gilligan was a member of the British Fascists. An article in the Sheffield Telegraph reported (somewhat inaccurately) that Gilligan and Toone were enrolled as members on the journey home from Australia, and he began to speak at events. For example, a letter from him was read aloud at a meeting of the British Fascists at Bognor in June 1925, in which he said “I am very strongly with the Fascist views”. Most infamously, he wrote an article called “The Spirit of Fascism and Cricket Tours” for The Bulletin — the publication of the British Fascists — in May 1925, in which he said: “In … cricket tours it is essential to work solely on the lines of Fascism, i.e. the team must be good friends and out for one thing, and one thing only, namely the good of the side, and not for any self-glory.” Gilligan was not the first to make such links — and it perhaps reinforces the notion that he held a “boy scouts” view of fascism — but those others did not enjoy his high profile as the England captain.

This article at least provoked a reaction in the Daily News, which openly mocked Gilligan:

“It is a little astonishing to find Mr A. E. R. Gilligan, the captain of the English Cricket Team, airing his views in the pages of a journal which describes itself as ‘the Only Organ of the British Fascists’; it is still more astonishing to see what he says. ‘In these cricket tours,’ declares the cricket captain in his most diverting sentence, ‘it is essential to work solely on the lines of Fascism.’ As a humorous writer Mr. Gilligan may be congratulated on the short essay in which he plays variations on this novel theme . He will, as the saying is, have his little joke. It was no doubt only lack of space which cut short even more fantastic flights of his imagination.”

The writer continued his theme, making sardonic suggestions that cricketers might take the field in black shirts, marching on to the sound of military drums, but cautioned:

“Yet perhaps it would be kind to warn Mr Gilligan, who has been away for some time, that jokes of this kind are a little dangerous, people take politics so very seriously and they may only fail to see what on earth cricket has to do with Fascism … Mr. Gilligan has been a very popular figure on the cricket field; one may humbly suggest that he may not be so welcome in the field of politics, or even in the field of humorous essay-writing.”

Gilligan played little cricket in the 1925 season, apparently because of injury, and so was not selected for the only fully representative game, the Gentlemen v Players match at Lord’s. Instead, Arthur Carr led the Gentlemen, which was an indication of where the selectors’ thoughts lay. It is interesting to speculate whether Gilligan’s open support of fascism might have counted against him had he played more often, but it is probably safe to conclude that it wouldn’t. Because he was one of the Test selectors for the 1926 Ashes series — although unlike Warner, the chairman, he was always silent about what went on at the meetings and does not seem to have rocked the boat too much — and led an MCC team in India in 1926–27 which, as we shall see, had far-reaching consequences. And in his wider life, his membership did not prevent him from being awarded the Freedom of the City of London in 1926.

Even when it became clear that fascism was a major threat in Europe, Gilligan’s views never seem to have been brought up. But if he and Toone had hoped to establish the British Fascists in Australia, their efforts were largely wasted. Although fascism did become established in Australia, it was not through the British Fascists. And that organisation did not last much longer either. In the history of fascism in Britain, they were soon eclipsed by the far more influential British Union of Fascists, and practically vanished after 1926. However, as late as 1927, Gilligan was still associated with them, giving a speech at an event in Ealing.

Gilligan’s first-class career continued intermittently until 1932, but after the 1924–25 tour, he was never in contention for the England team again. He did respectably well with the ball in 1926 and 1928 without ever approaching his form from 1923 and 1924, and he batted quite well, even scoring a thousand runs in 1926. But after 1928, he barely played. His last significant cricket came when he was selected to lead an MCC team in India during the 1926–27 season. And that is a whole other story…