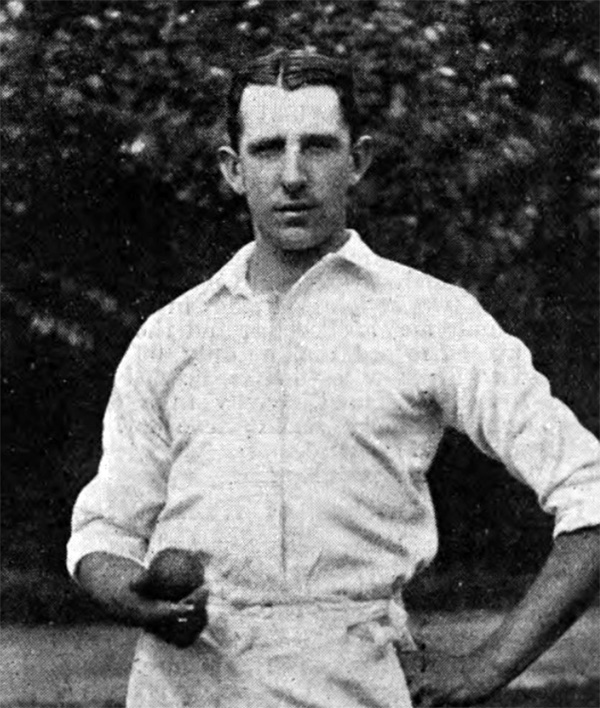

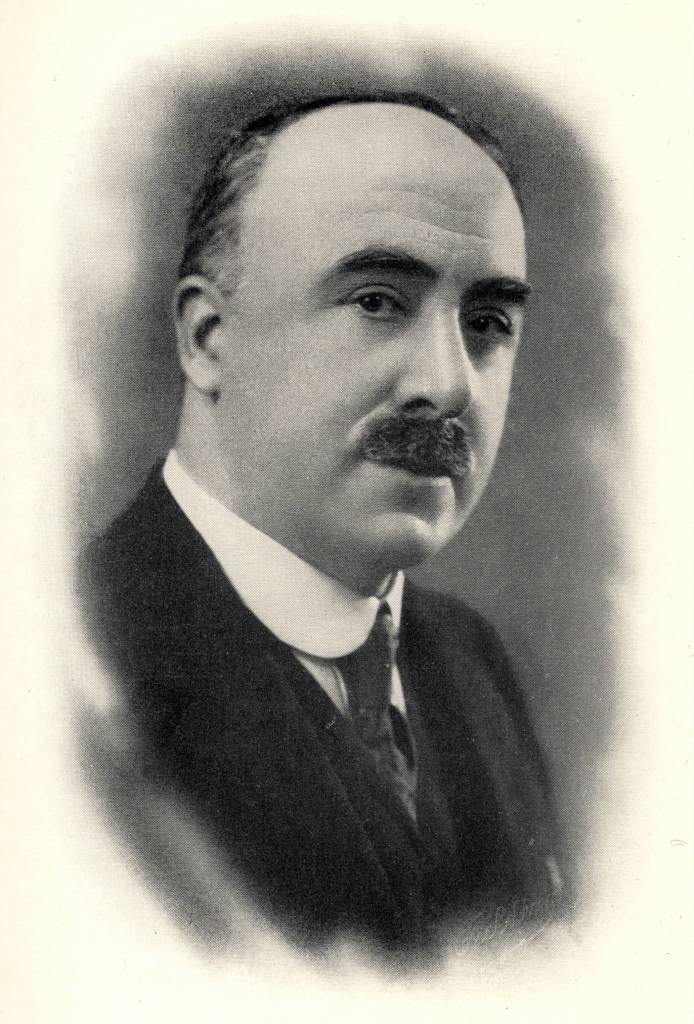

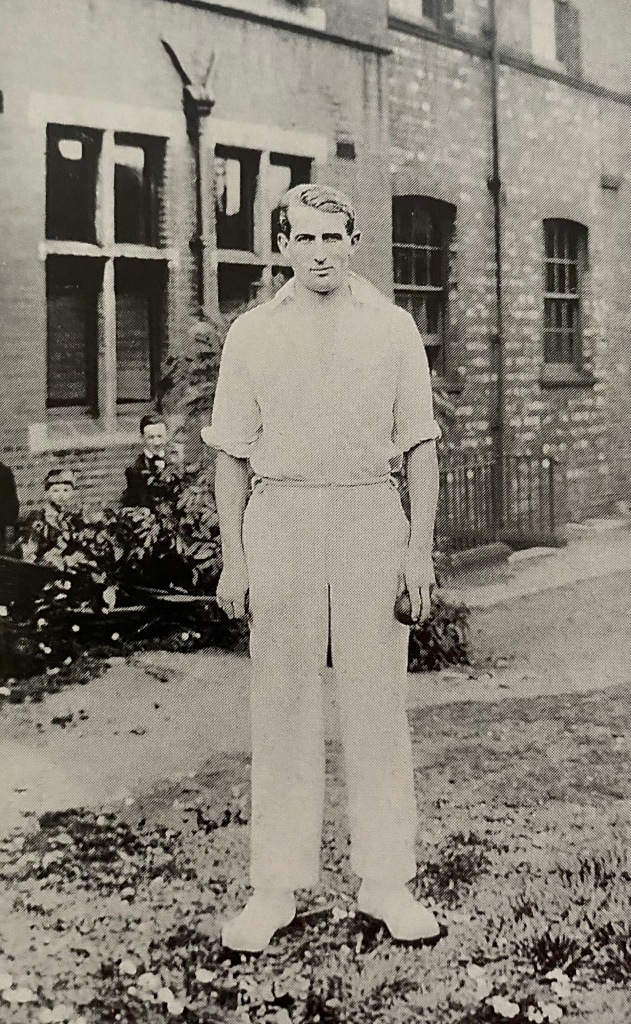

Abe Waddington photographed around 1922 (Image: Yorkshire County Cricket Club (1997) by Mick Pope)

Abe Waddington was a Bradford-born left-arm swing bowler who began playing for Yorkshire in 1919. Scarred by his experiences during the First World War, he was never a typical county cricketer. Quick to anger and always willing to stand up for himself, he became a dominant figure in the Yorkshire dressing room and a crucial part of the team on the field. Most importantly, he was an immediate success when given an opportunity after first-class cricket resumed. After another good season in 1920, he was fast-tracked into the England Test team through a combination of optimistic hope that he could recreate the success of his fellow left-armer Frank Foster from ten years earlier, and a lack of viable alternatives given how weakened English cricket had been by the war. But he was an abject failure as part of the England team that lost 5–0 to Australia in 1920–21.

That was the end of Waddington’s Test career and he did not come near representative cricket again. He never played in the Gentlemen v Players match at Lord’s, the most prestigious fixture outside Tests in this period, and only appeared for the Players in end-of-season festival matches at Scarborough (in 1920) and Folkestone (in 1925). And over the following seasons, Waddington’s career went into a strange kind of limbo. Although he took over 100 wickets in 1921 (at the more-than-respectable average of 18.94), a later edition of Wisden judged his form that year to be modest. The review of Yorkshire’s season in The Cricketer maintained that Waddington’s form in the early part of the season was poor — he took only 38 wickets in May and June — but he recovered later.

Waddington’s best season statistically came in 1922, when he captured 133 wickets at 16.08. Finally, Wisden found some words to praise him, albeit faintly: “Waddington was, on occasions, more successful against strong sides than he had ever been before. He had days of astonishing success and once, at least, bowled with a bewildering swerve that recalled George Hirst at his best.” That season, he took eight for 34 against Northamptonshire, the best first-class figures of his career, a spectacular seven for six to bowl out Sussex for 20 and eight for 35 against Hampshire. The Cricketer review noted that Waddington was at his best on difficult batting wickets, but had a qualification: “At his best … [he] was at times unplayable; but he was subject to off days, and he has never yet shown his best form at the Oval.” That sense of underachievement against the best teams was perhaps best captured by Neville Cardus’ lament in 1921 that Waddington was “ever raising hopes that real greatness will come from him, only to disappoint again and again”.

And, although no-one could have suspected it at the time, 1922 marked the turning point of his career. During an inconsistent 1923 season, by which time he had fallen well down the pecking order of Yorkshire bowlers behind George Macaulay and Roy Kilner, he had just begun to find his form after a poor start when he slipped while playing at the Fartown Ground in Huddersfield against Leicestershire. The resulting shoulder injury ended his season, apart from one brief, abortive come-back match, and he was never quite the same bowler. Given his already known limitations, there was no way for him to reach to the top again. When he returned in 1924, he took only 69 wickets and his average climbed above 20 — high for a Yorkshire bowler in this period. The Cricketer stated: “Waddington was disappointing, and seems to have lost a good deal of his pace and devil, though he still maintains a beautiful delivery.”

But in many ways the final years of his career were overshadowed by events in the 1924 season, when his and Yorkshire’s ultra-competitive attitude on the field crossed over, in the eyes of the cricketing establishment, into lack of sportsmanship and outright dissent.

From late in the 1922 season until almost the end of 1926, Yorkshire were the dominant team in English cricket. Solid but unspectacular batting was backed up by incredibly strong bowling. The Yorkshire attack was regarded as almost unhittable; allied to strong and well-placed fields, even in benign batting conditions Yorkshire in the field could dry up runs from almost any team and dismiss them cheaply. Waddington was not a leading member of the attack but was strong back-up to Kilner and Macaulay; he, Wilfred Rhodes and Emmott Robinson were there to keep on the pressure so that the opposition had no chance to relax.

But there were some issues for the Yorkshire team. For example, unlike some of the southern counties, Yorkshire’s first-choice eleven was almost entirely professional. The only amateur was usually the captain, at best a nominal leader whose responsibility was largely disciplinary. The tactical direction for the team was set by Rhodes, the senior professional, and the leading bowlers. This troubled the amateur establishment.

Yorkshire in 1924. Back row: Edgar Oldroyd, Roy Kilner, Herbert Sutcliffe, George Macaulay, Maurice Leyland, Emmott Robinson, Billy Ringrose (scorer). Front row: Abe Waddington, Wilfred Rhodes, Geoffrey Wilson (Captain), J. S. Stephenson, Arthur Dolphin, Percy Holmes (Image: The Cricketer Annual 1924–25)

Furthermore, the Yorkshire eleven became increasingly truculent; there were several minor incidents in 1922 and 1923, from the team deliberately missing their train in protest at a decision to finish one game early, to accusations that the bowlers deliberately scuffed up pitches. And the team’s ultra-competitive attitude began to anger the souther, amateur-dominated counties such as Middlesex and Surrey. Rumours swirled about incidents involving Yorkshire; the Times correspondent wrote in 1924: “The fire now breaking out has been smouldering for some time. Last season I heard all sorts of hints and rumours, but nothing definite.” And there are just enough hints that the Yorkshire captain, the ineffectual Geoffrey Wilson, was struggling to control the team; nor was he too happy with the ultra-competitive nature of the team of which he was in nominal charge. But as they became more dominant on the field, the team became increasingly unpopular off it, except with its own supporters, which still followed Yorkshire passionately and — particularly at Sheffield — extremely vocally.

The chief culprit for causing upset to the opposition was George Macaulay; his aggressive attitude towards batters, including verbal attacks, annoyed many opposition amateurs. But the catalyst for a huge backlash in 1924 came from an incident involving Waddington. If part of the issue concerned the perception of Yorkshire by other counties, Waddington’s personality played a major part.

Martin Howe wrote of Waddington, in his 2010 article for the Yorkshire yearbook: “Abe resented the class and hierarchical distinctions of the game — for example, the rule that professionals should touch their cap to any amateur player and the dominance of gentlemen amateurs in the governance of cricket. His antipathy had been fuelled by his experiences of the officer class during the war and, perhaps, by the haughtiness of his captain on the the tour of Australia.” Howe mentioned J. W. H. T. Douglas’ habit of leaving the team alone while he attended social functions, but one other incident — presumably told to him by Waddington’s relatives to whom he spoke in writing the article — when Douglas “publicly admonished” the fast bowler and professional Harry Howell for daring to address Rockley Wilson as “Rockley” rather than “Mr Wilson”, as professionals were expected to do when talking to amateurs. And yet this might be a garbled recollection of something which actually applied to Waddington himself.

An article by the journalist (and later the editor of Wisden) Sydney Southerton in 1928 recalled an occurrence from the 1920–21 tour:

“The … story concerns ‘Abe’ Waddington, E. Rockley Wilson, and P. G. H. Fender. The Surrey captain, I should say, is known among cricketers as ‘Percy George.’ Waddington, in the pavilion one day, was warmly discussing some incident, and repeatedly referred to Wilson as ‘Rockley’. After a time, J. W. T. Douglas, the captain, interposed with ‘A little less of the Rockley, please.’ Waddington, in apparent surprise, retorted ‘Why not? He calls me Abe.’ ‘Who calls you Abe?’ asked Douglas. ‘Why Percy George,’ returned Waddington very neatly.”

Howe also suggested that while playing for Yorkshire, Waddington was prepared to slow the over rate, argue over umpire’s decisions which he believed to be incorrect, and “sledge” opposition batters — something that was considered unsporting at the time but something of a habit of the Yorkshire team. He also had a reputation for reacting badly when decisions went against him. Newspaper reports from the 1920–21 tour singled him out for this, but noted that Douglas was equally guilty. The latter also had a reputation from throwing up his hands in frustration when bowling, behaviour hypocritically acceptable for an amateur captain but a target for criticism in the case of Waddington.

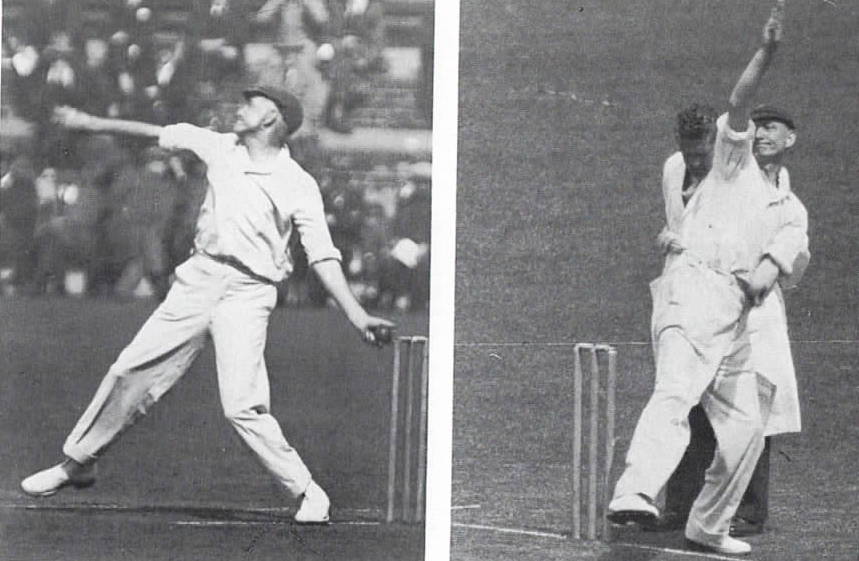

A short section of film showing Waddington bowling in close-up from the early 1920s

No doubt Waddington was aware of these different levels of acceptance and resented them. But his irritation might have been heightened because of where he had come from, because he did not have a typical background for a professional cricketer. He could quite likely have played as an amateur if he had taken a position at his family business — and many players from other counties would have done so. Perhaps the security of that family background also gave him more confidence to make himself heard than would have been typical for a professional who needed to keep his social “betters” mollified. Herbert Sutcliffe wrote of Waddington in his 1935 autobiography: “He always was a genial fellow in the dressing room; a man with a rare personality, proof of which is shown by the fact that whenever there was a discussion of any kind in the dressing room, Abe generally ruled it, to all intents and purposes, the chairman.” Such confidence would not have been found in many professional dressing rooms in 1920s England; yet alongside men like Sutcliffe, who had been an officer in the war, Waddington somehow fitted in perfectly; his philosophy and temper exemplified the Yorkshire attitude that made the team so successful in this period.

Many of these issues came together in 1924. The seeds for what happened were sown when Yorkshire faced Middlesex — a team dominated by amateurs and perhaps the county that most represented the traditional English cricket establishment — at Lord’s. Roy Kilner, Macaulay, Herbert Sutcliffe and Percy Holmes were all absent, playing in a Test trial. Middlesex lacked Patsy Hendren and Jack Hearne, important players, but managed to find quality amateur replacements. The threadbare Yorkshire bowling was taken apart; Waddington conceded 116 runs from 42 overs and Wilfred Rhodes was struck four times for six, including twice in successive deliveries. Yorkshire were defeated by an innings and 152 runs. This was the beginning of an unaccustomed slump for the champion county; including the match at Lord’s, Yorkshire won just three and lost two of ten games. Therefore the team were under some pressure when they faced Middlesex once again, this time at Sheffield in early July.

Unlike the previous encounter, both teams were at full strength. On the first day, in front of a crowd of 20,000, a series of tactical mistakes by Yorkshire helped Middlesex to score 358. But this was utterly overshadowed by an incident in the first hour, which the Yorkshire Post described as “an unseemly outburst on the part of a section of the crowd.” The spectators were furious when the highly experienced umpire Harry Butt turned down an appeal against Greville Stevens from Abe Waddington’s bowling. The umpires took the view that Waddington had inflamed the situation by his reaction to the decision. He certainly had a habit of gesticulating in anger in such situations. However, the way the crowd reacted to Waddington — and how he played up to them — made the situation far worse, and amid considerable tension, play was halted until everyone calmed down. The Middlesex amateurs were notably shaken up by the experience.

On the second day, in front of 11,000 spectators, Yorkshire lost three quick wickets — those of Emmott Robinson, Macaulay and Waddington — to lbw decisions. Again, it appears that the reactions of these players, particularly Waddington, caused the crowd to erupt. The Yorkshire Post related how the “popular side of the ground made no attempt to conceal their resentment at the decision in particular which dismissed Waddington. The jeering which followed was unseemly and uncalled for, and as a factor of disturbance to the batsmen no less than to the attacking side, it was especially to be condemned.” On the final morning, after Yorkshire were bowled out just short of Middlesex’s total, Middlesex batted for most of the remainder of the day to secure the draw and a crucial three points for their first innings lead, which took them to the top of the Championship table. But Alfred Pullin (“Old Ebor”) called the match “a sorry exhibition of ill feeling and bad manners.”

After the game, the umpires complained to the MCC about Waddington’s behaviour. The Yorkshire Committee were informed and the Selection Committee met on 14 July. According to the minutes of the meeting, after the committee read a report from Geoffrey Wilson, Waddington was summoned and the complaint was read to him. The player was cross-examined and then asked to leave the room while the committee discussed the matter. They concluded that they would invite the MCC Cricket Committee to fully enquire and hear from all sides. The minutes record: “This was considered only fair to Waddington who was himself most anxious that the enquiry should take place at once.” The committee also resolved to see what could be done about the behaviour of the spectators at Sheffield.

While the matter was under discussion by the MCC, Middlesex announced that they would not play Yorkshire in the 1925 season; the match in question had already been set aside for Roy Kilner’s benefit. The MCC Committee met to discuss the matter on 21 July; the brief minutes make it clear that the enquiry was only held because Yorkshire would have found it hard to summon the umpires and other witnesses to judge for themselves. The chairman pointed out that other than in the matter of their appointment, the MCC did not get involved with umpires but only acted on behalf of the county captains who picked them. The treasurer, Lord Harris, wrote a report, which was sent to Yorkshire.

The Yorkshire Committee met on Saturday 26 July. They agreed to reprimand Waddington, but were equally concerned with repairing the damage to their relations with Middlesex: Lord Hawke and the Secretary, Frederick Toone, said that they would look into the matter of the fixtures for next season. It was also agreed to make a statement to the press:

“The Cricket Sub-Committee have, as requested, held an enquiry into the umpires’ report of Waddington’s alleged unsportsmanlike behaviour in the Yorkshire v Middlesex match … [The Sub-Committee] reports as follows:

As regards several incidents reported by the umpires, it is obvious that the evidence is flatly contradictory. The Sub-Committee are, however, satisfied that an umpire of Butts’ experience, impartiality, and strength of character would not take the extreme step of reporting a player without having received extreme provocation, knowing the tendency of players to gesticulate when a decision does not please them. Butts’ report is confirmed by his colleague Reeves. They are unable to accept Waddington’s claim of complete innocence. The Committee realise that under the circumstances of the moment — i.e. that there was much excitement certainly among the crowd and possibly on the field — Waddington may have been affected thereby, and may not have appreciated how easily any motion of dissent from a decision can induce excitement. Therefore, if a decision lay with the MCC, and not, as it does, with Waddington’s employers, they consider that a serious warning to Waddington that he must control his feelings would meet the case.”

The Yorkshire Committee agreed to write in thanks to the MCC and to inform them that their recommendations would be implemented. They also agreed to “suppress any unseemly conduct” from the spectators on the Yorkshire grounds. Waddington, after meeting Lord Hawke, wrote to the secretary of the MCC:

“Dear Sir,

I beg to express my regret that any action of mine during the Yorkshire v Middlesex match at Sheffield should have caused unpleasantness, and should have had the effect of my being reported by the umpires. I am exceedingly sorry, and it shall not occur again.

Yours obediently,

A. Waddington.”

Perhaps it is relevant, however, that Waddington was never dropped from the Yorkshire team at any point in the proceedings. After some cagey diplomacy, it was confirmed in August that next season’s fixtures with Middlesex would go ahead. And yet it is not hard to imagine Waddington’s private fury at having to make such a public apology. The repercussions were considerable though. Relations between the Middlesex and Yorkshire teams were frosty at best until the Second World War, and their matches were often keenly (and bitterly) contested. And it cost Geoffrey Wilson the captaincy; he was replaced for 1925 by A. W. Lupton, a former major in the British Army, who imposed a little more discipline on the team, restoring their popularity with other counties without sacrificing their competitiveness. In the shorter term, it also cost George Macaulay — who somehow became the focus of all the criticism of Yorkshire despite Waddington’s role in the Sheffield controversy — his England place; having been on the fringes of the Test team, he was dropped (admittedly after an anaemic performance in the Headingley Test against South Africa) and left out of the MCC team that toured Australia in 1924–25 despite topping the first-class bowling averages for 1924.

As for Waddington, he was never in contention for a Test recall, and his season was disappointing. The Cricketer stated: “Waddington … seems to have lost a good deal of his pace and devil, though he still maintains a beautiful delivery.” Even so, Yorkshire sneaked home to win their third consecutive County Championship after Middlesex crumbled under the pressure of leading the table at the end of the season. As Yorkshire found some late form to win nine of their last sixteen games, Middlesex lost a crucial game against Gloucestershire. Despite being expected to win easily — Gloucestershire had not beaten them since 1906 — and having bowled the home team out for 31 in the first innings, Middlesex lost by 61 runs after the young Walter Hammond scored 174 not out and Charlie Parker took a hat-trick in each innings. But reviews of the season — especially in The Cricketer, edited by the former Middlesex captain Pelham Warner — were critical of Yorkshire and suggested that Middlesex were the better team.

The remainder of Waddington’s career was something of an anticlimax. He took over a hundred wickets in 1925 — a considerable achievement in a good season for batting. His 109 wickets cost 20.24, and Wisden said that “Waddington enjoyed a well-merited success”. But even then, his bowling was not quite what it once had been. His decline was even more marked in 1926, when he took 78 wickets at 23.30; Wisden again noted his loss of form but expected him to recover. The Cricketer suggested that part of the problem was that he “seemed to rely too much on the leg theory” (i.e. directing the ball at leg-stump with a ring of fielders on the leg-side). Waddington was not alone in being less effective, and Yorkshire struggled to bowl teams out that season. But in 1927, he managed just 45 wickets at 32.02; Wisden judged that his “work was only occasionally worthy of his reputation”. And The Cricketer said: “Waddington showed a drop in his former all-round form. A bowler of his type is severely handicapped in a wet season. He still has his beautiful action, but his arm has begun to drop slightly when delivering the ball.”

It transpired that 1927 was his final season in first-class cricket. The Yorkshire selectors, aware that the team was in decline and that changes needed to be made, opted for a radical approach and decided to offer the captaincy to Herbert Sutcliffe, a professional, after the incumbent, A. W. Lupton, resigned. Their thinking was that by jettisoning the amateur captain, who was never worth his place on cricketing skill, the team would be strengthened. The ensuing controversy rumbled over several months before the committee quietly reversed course and appointed another amateur. But lost in the furore was another important decision. In September 1927, the selection committee, in the wording of the minutes from the meeting, “throughly thrashed out” the team for the following season. The result of the deliberations was that Waddington and Arthur Dolphin, two of the “three musketeers” associated since their shared First World War experiences, would not be required regularly for 1928. In effect, they were dropped. The committee offered them an £8 per week retainer for when they were not needed, although they had to agree to be placed with a Yorkshire club. This was a standard rate but compared unfavourably to the wages for capped players of £11 for each home game and £15 for each away game; especially when the team usually played two games per week.

Dolphin accepted the terms but Waddington did not. He seems to have taken his time to decide, and it was not officially announced in the press until December that he was to retire from first-class cricket, although he had already made it clear that he did not want to be attached to a club as a reserve. Therefore, his career with Yorkshire was at an end, and he told the press that he had been approached by several clubs. The same announcement that said he was done with Yorkshire revealed that he had signed with West Bromwich Dartmouth Cricket Club in the Birmingham League. In January, he was given a grant of £1,000 by the Yorkshire Committee for his services. This was a provision of the regulations for Yorkshire players — long-serving players who had not had a benefit were generally given at least £50 for each season they had played. Waddington had not been granted a benefit before his release.

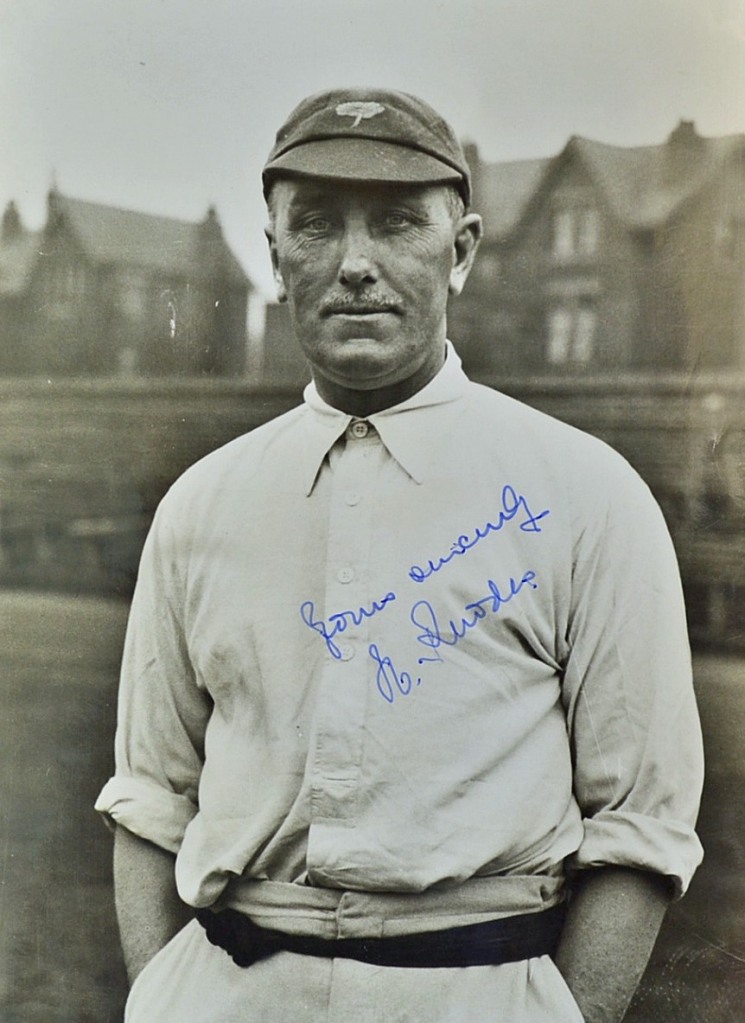

Roy Kilner in 1922 (Image: Wikipedia)

As it happened, he might have played quite regularly in 1928 had he accepted the terms. The sudden death of Roy Kilner (the third of the musketeers) just before the 1928 season left Yorkshire desperately short of bowling, and Waddington would almost certainly have been recalled had he been available. As it was, Waddington paid tribute to his former team-mate in the press and was a pall-bearer at his funeral, alongside several of his Yorkshire team-mates.

In August 1928, Waddington signed for Accrington in the Lancashire League. West Bromwich Dartmouth had hoped to retain him, but a change to the league rules made it impractical — the authorities wanted to make sure professionals lived in the area and attended their club for several weeknights for coaching purposes. Waddington, still living in Bradford, could not do this. He played for Accrington in 1929 and 1930; he took 79 wickets at 14.46 in his first season and 57 at 16.17 in his second. These were decent, but not spectacular, returns. At the end of the 1930 season, although he had offers from other clubs, Waddington retired from professional cricket to concentrate on the family business.

But for a man like Waddington, that was not the end of his adventures…