The Somerset team which surprisingly defeated Middlesex at Weston-super-Mare in 1922 contained nine amateurs. Back row: A. Young, T. C. Lowry, M. D. Lyon, J. J. Bridges, S. G. U. Considine. Front row: E. Robson, W. T. Greswell, P. R. Johnson, J. Daniell, J. C. White, J. C. W. MacBryan. Only Young and Robson were professionals.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the County Championship was dominated by northern teams. Apart from Middlesex’s titles in 1920 and 1921, the only County Champions between the two world wars were Yorkshire (twelve times), Lancashire (five times), Nottinghamshire (once) and Derbyshire (once). Kent and Surrey, although they never finished as champions, were always competitive; Sussex, like Derbyshire, were better in the 1930s, while Gloucestershire and Essex also had their moments. The remaining counties generally struggled. Glamorgan, Somerset, Warwickshire, Hampshire, Northamptonshire, Leicestershire and Worcestershire were often to be found battling in the lower reaches of the table and never mounted a realistic challenge for the Championship. There were several reasons for this, but the main ones were financial. Lacking the facilities of some of the bigger clubs and attracting far fewer spectators and members, these teams lived a precarious existence. On more than one occasion, some looked likely to fold completely and were often dependent on wealthy benefactors to keep them going. This had a lasting impact on the teams; they could not employ as many professionals as other counties, or offer terms attractive enough to prevent players seeking a better deal elsewhere, whether at another county or in league cricket. Those professionals who remained loyal received lower wages than their counterparts at the bigger clubs and received far lower sums if they were awarded a benefit.

The result was that these counties relied on amateurs who required the payment of nothing more than expenses. While other teams could afford to employ “shamateurs” — men who held that status in name only, receiving surreptitious payments to allow them to play for their counties (an issue that had been festering for many years) — the counties which were struggling needed genuine amateurs whom they did not need to pay. As many of these were only available some of the time, the result was often an unsettled and constantly changing team. In Gentlemen and Players (1987) by Michael Marshall, Glamorgan’s Wilf Wooller recalled: “We played some of our indifferent amateurs for economic reasons, and it has to be said that Maurice Turnbull liked to have a few cronies along with him as social companions.” This cannot have been easy for the professionals who were forced to make way.

The Kent accounts for 1930 provide some insight into the savings that could be made. The expenses claimed by amateurs amounted to just 11 per cent of the outgoings paid to players for Championship matches, even though over the season 37 per cent of the available places were filled by them. Furthermore, the Findlay Commission — a committee appointed in 1937 by the MCC, under the former Oxford and Lancashire player William Findlay, to examine the problems facing counties — revealed that over the three year period from 1934 to 1936, Somerset was the only county whose income (excluding the Test match profits shared between all the counties) was greater than their expenditure; Somerset usually played a higher proportion of amateurs than other teams.

The problem was that it was increasingly difficult to find amateurs. Fewer and fewer men whose social background precluded them becoming professionals — the upper-middle classes, the university graduates, the former public schoolboys — could spare enough time to play regular county cricket; their financial situations compelled them to have full-time jobs. In his excellent Cricket and England (1999), Jack Williams provides some statistics on amateurs between the wars. In 1920, 39 per cent of appearances in the County Championship were made by amateurs; this figure fell to 20 per cent by 1930 and 19 per cent by 1939. If the northern counties were almost always all-professional apart from the captain, southern counties had a much higher proportion of amateurs. In 1920, only two professionals appeared for Somerset in the entire season; only four played that season for Middlesex, the County Champions. It was a conscious policy at Sussex until 1928 that there should be four amateurs in every team. The contrast between north and south could be clearly seen in the percentage of amateur appearances at several counties in 1930: the figure was nine at Lancashire, 32 at Kent, 37 at Middlesex and 55 at Somerset. In 1939, the amateur percentage at Kent was 31, at Somerset 29 and at Worcestershire 25. And a final figure: in 1930, only 24 amateurs appeared in at least 20 County Championship matches. Given a limited pool from which to draw, it is unsurprising that the stronger teams quickly acquired the best amateur talent, leaving the weaker counties casting around desperately for whoever was left.

Aside from any financial considerations, an important factor in the desperation for amateurs was connected to captaincy. In this period, all teams were captained by amateurs. The reasons were largely based around class discrimination, no matter how contemporaries tried to dress it up. But this led to problems. The scarcity of amateurs who could play regularity meant that many counties had a rapid turnover of leaders. This even extended to the stronger sides: Yorkshire, where the captain was often the only amateur in the team, had seven captains between 1919 and 1939, as did Sussex.

Worcestershire’s team in the late 1920s. Back row: C. R. Preece, J. B. Higgins, C. V. Tarbox, J. F. MacLean, H. L. Higgins, H. O. Hopkins, L. E. Gale. Front row: C. F. Root, M. K. Foster, The Earl of Coventry (President), F. A. Pearson, Hon. J. B. Coventry (Image: A Cricket Pro’s Lot (1937) by Fred Root). Only Preece, Tarbox, Root and Pearson were professionals. Fred Root dated this photograph to 1927, although it appeared in Tatler on 28 May 1924 and shows the team which played Glamorgan at Worcester on 10–13 May 1924.

The effect was heightened lower down the county table. In the same period, Leicestershire had ten captains; Northamptonshire had nine. One-season captains were relatively common, as was the phenomenon of having multiple leaders in a single season: with no suitable amateur available, Leicestershire made no appointment in 1932 and were captained by six different men. And the lack of suitable amateurs for the weaker counties meant that some captains were very inexperienced. E. W. Dawson captained Leicestershire in 1928 as a 24-year-old who had graduated from Cambridge the previous year. At Northamptonshire, Alexander Snowden — who had first played for the county as an eighteen-year-old amateur in 1931 — led the team at the beginning of 1935, aged just 21. His Wisden obituary in 1982 stated: “Although [Snowden] won the toss in his first ten matches, he was not a success; he had insufficient confidence in himself and the side rather lost confidence in him. The experience had a disastrous effect on his form and in 30 innings his highest score was only 29.” The episode largely finished him as a first-class cricketer, but there was an unfortunate side-effect for his county. Snowden’s father was a local councillor and his donations had been instrumental in saving Northamptonshire from bankruptcy in 1931; at the end of the 1935 season he gave an angry speech at a meeting of the Peterborough and District Cricket League which blamed the Committee for the poor form of the county and his son that year. He hinted that all was not well within the team and indicated that the treatment of his son meant that he was ending his support for the club.

The need for amateur captains resulted in some other oddities. When the regular captain was unavailable at Northamptonshire in 1921 and in 1932, the team was captained by an eighteen-year-old. And many amateur captains had frankly appalling playing records and were included in the team purely through their leadership role. But stronger counties also fell into these traps; the permanent Lancashire captain in 1919, Miles Kenyon, had never played first-class cricket. Yorkshire, too, appointed some very inexperienced captains who were frankly out of their depth, resulting in the muddled attempt of the Yorkshire Committee to appoint Herbert Sutcliffe in 1927.

This is not the place to discuss the perception of amateurs, nor the contemporary conviction that they were essential to English cricket. While teams like Kent or Sussex favoured amateurs for stylistic, philosophical and social reasons, counties which were struggling financially simply needed to get eleven players onto the field without going bankrupt. The lack of suitable candidates led to some frankly strange selections.

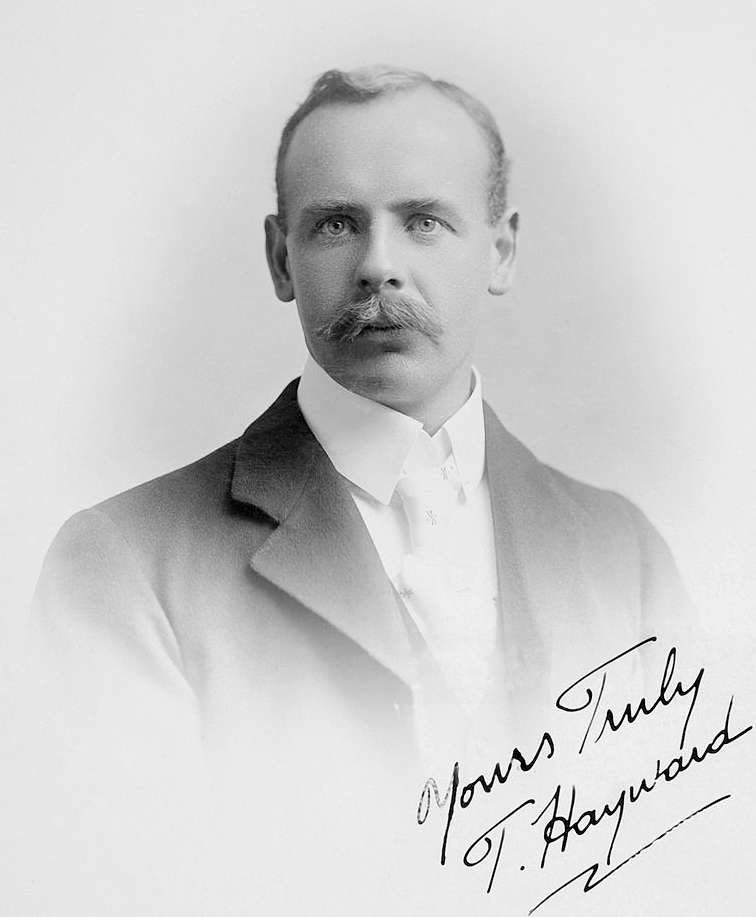

Reginald Moss pictured in the Oxford University cricket team in 1890

Perhaps the most extreme example of the need for amateurs came in 1925 when Worcestershire selected the Reverend Reginald Moss, who was the Rector of Icombe — a village near Stow-on-the-Wold, between Cheltenham and Oxford — at the time. It was not particularly remarkable that he was a clergyman and although this was his only appearance in the County Championship, he had previous experience of first-class cricket, playing for Oxford University. The problem was that he played for Oxford between 1887 and 1890, and his last first-class appearances had been in 1893. When he played for Worcestershire, he was 57 years old, which makes him the oldest cricketer to play in the County Championship; the gap of 32 years between appearances is also a record. He had been a reasonable cricketer; apart from playing for Radley College and Oxford, he had played some minor matches for Lancashire in 1886, in the Minor Counties Championship for Bedfordshire between 1901 and 1909, and had played for Herefordshire. He had also worked as an Assistant Master at Malvern College. So apart from the minor inconvenience of his age, he was the ideal amateur in many ways.

It is not clear what particular circumstance prompted Worcestershire to play Moss because nothing about him stood out; his regular teams at the time were the Old Biltonians (he had attended Bilton Grange Preparatory School), Stow-on-the-Wold and Bourton Vale. His selection drew plenty of attention but Pelham Warner in The Cricketer was scathing: “Without wishing in any way to belittle the skill and enthusiasm of an experienced cricketer, we cannot help stating that it seemed a confession of weakness on the part of Worcestershire to include the Rev. R. H. Moss in their side against Gloucestershire at Worcester on Saturday last.” In any event, the game was underwhelming for Moss. He did not bowl in Gloucestershire’s first innings and batting at number nine in the first innings, he scored 2. In the second Gloucestershire innings, he bowled three overs for five runs and took the wicket of the opener M. A. Green. Batting at number eleven in Worcestershire’s second innings, he was the last man out, bowled by Walter Hammond for 0, as Gloucestershire won by 18 runs. Moss then faded back into obscurity; he and his wife Helen lived peacefully with their three children. He died at the age of 88 in 1956, but his obituary did not appear in Wisden until 1994.

The case of Moss was somewhat unusual as weaker counties were more inclined to try young amateurs just out of school in the hope of finding someone who could strengthen the team or prove to be a potential future captain. Very occasionally, a good player was uncovered; but most young amateurs of any talent, particularly those who went to Oxford or Cambridge, were attracted to the stronger counties. However, that is not to say that there are not some interesting stories to be uncovered. One of the more unusual is to be found in the tale of a fairly typical amateur experiment, a young player who appeared for Worcestershire in the mid-1930s.

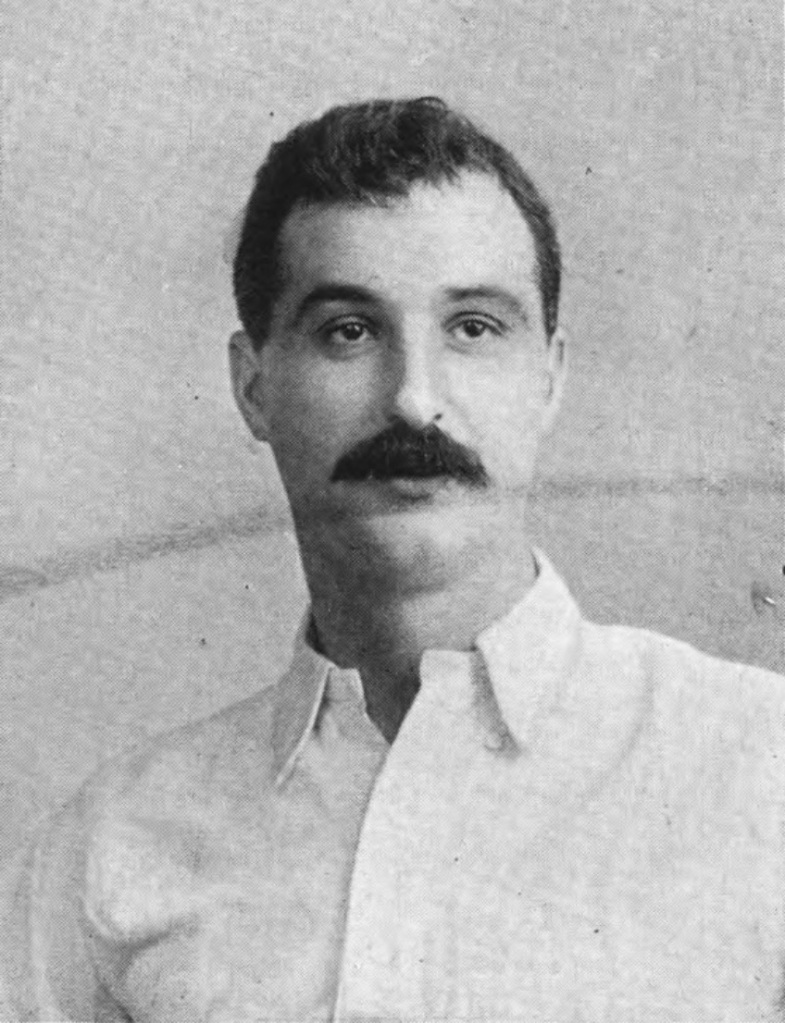

Cyril Harrison in 1935 (Image: Daily Mirror, 11 January 1936)

Cyril Stanley Harrison was born on 11 November 1915, the son of George Harrison and his wife Winnifred Jessie Bradley. His father worked as a bricklayer with the Salt Union but later became a prominent builder and a member of Droitwich Council. Cyril had five brothers and three sisters; he was the fourth to be born. He attended Worcester Royal Grammar School, where he made a name for himself primarily as a batsman. He also played football and rugby. In short, he was an ideal candidate to play as an amateur for a county which struggled to attract more glamorous names.

It was not long before Worcestershire noticed him. In 1933, Harrison played for the “Gentlemen of Worcester”. The following year, at the age of eighteen, he played for the county second eleven (obviously as an amateur) early in the season. On 9 June 1934, he made his first-class debut against Lancashire on 9 June, batting in the lower-middle order and bowling slow-left-arm spin. Apart from taking three for 89 against Nottinghamshire, he did little to suggest that he was a good enough player through the course of June. But at the very end of the month, he had his one success as a first-class cricketer. In the fourth innings, Hampshire needed 122 to defeat Worcestershire after the home team lost nine wickets for 74 in their second innings. Harrison — the fifth bowler to be used — took seven for 51 to bowl his team to an unlikely win by six runs (Hampshire had one man absent injured). At one stage his figures were 4–3–1–3. The wicket had broken up, assisting his bowling, but he flighted the ball very well. When the last pair came together, Hampshire needed fourteen to win and scored half of them before Harrison bowled Len Creese, the top-scorer, for 28. The delighted home supporters carried Harrison from the field, and he was awarded his county cap; as it transpired, this was somewhat premature.

Harrison kept his place for the rest of the season, but never approached this form again. Apart from taking three for 83 against Yorkshire, he never took more than two wickets in an innings, and never scored more than 28 with the bat. He finished the season with 150 runs at 6.25 and 25 wickets at 36.92. Although some critics suggested that he needed to bowl a little quicker to be successful, he was viewed as a promising player in a team which lacked stars. But the key attraction was almost certainly that he was an amateur. So when he turned professional before the 1935 season, he immediately lost most of his appeal. We do not know why he made the change — as we shall see, he was studying to be a surveyor — but it effectively signalled the end of his first-class career.

Harrison only played twice more for the county; after conceding none for 101 in 17 overs against Sussex in his first match of 1935, and bowling only seven wicketless overs against Lancashire in his next, he was dropped from the team, never to return. The emergence of Dick Howarth and the success of Peter Jackson that season left little room for an inexperienced spinner, particularly one who now required payment without any guarantee of being effective. Had he remained as an amateur, perhaps they would have persisted with him a little longer.

Harrison therefore looks like another of the many cases of a young cricketer enjoying some early success before fading away and living the rest of his life in obscurity. But this was not quite the case. At the beginning of 1936, Harrison featured in the newspapers for reasons entirely unconnected to his cricket.

Away from the sports field, Harrison was a trainee surveyor with Worcester Corporation; he was an articled clerk to the Worcester town planner. On 8 January 1936, he was due to travel to sit an examination in London with the Chartered Surveyors Institute. He had arranged to travel by train with a friend — a colleague called Mr Dodd. Harrison’s fiancé, the 19-year-old Mary Baxter, accompanied him early that morning from his home in Droitwich to Worcester, where he said goodbye to her at the train station before heading to meet his friend on the train. He subsequently disappeared without trace. He never arrived for his examination, which was to take place over two days on 9 and 10 January, nor did he return to his family. His disappearance was reported to Scotland Yard, and his family put out a statement: “Cyril seemed fit and healthy, and very keen on his work. We know of no friends he might have visited outside Droitwich or Worcester. Mr and Mrs Harrison cannot explain his disappearance, and they are extremely worried.” Several newspapers, including the Daily Mirror, which printed Harrison’s photograph, carried the story.

After more than a fortnight, the mystery was solved when Harrison finally wrote to his parents to explain where he was. The Birmingham Daily Gazette told the story on 28 January; most other newspapers had forgotten him by then. A few days after Harrison’s disappearance, a man from Droitwich called R. C. J. Marvin, who had intended to look for work in London, wrote to his family from an address in Bayswater. Marvin’s family suspected that he was with Harrison, and contacted the latter’s family; George Harrison and Mary Baxter therefore travelled to the address to see Marvin on 12 January, only to discover that he and another man — whose description matched that of Harrison — had left the previous day. Shortly before the story was printed in the newspaper (no specific date is given), Harrison wrote to his parents from Southampton saying he was safe; at the same time, Marvin wrote to his own parents to say that he and Harrison had left London on 11 January after seeing the latter’s photograph printed in a newspaper. Marvin reported that “they had both had a good time and were looking for work.”

Kidderminster Cricket Club in 1951; Harrison is seated on the front row at the far left (Image: Sports Argus, 21 July 1951)

Unfortunately, the newspapers are silent on what happened next. We do not know if Harrison ever sat his examination, what prompted his disappearance or if he changed his career. The only clue comes on the electoral register for 1938–39, which reveals that he was still living with his parents in Droitwich. In mid-1939, he married Doris Mary Baxter in Droitwich. There is no clear evidence of him on the 1939 Register for England and Wales which might suggest that he had already joined the armed forces. Mary was listed living with her parents in Droitwich, but on the electoral register for this period, the newly-married couple share the same address.

Although details are scarce, Harrison seems to have served with the Royal Engineers during the war; there is a record of his promotion to sub-lieutenant in 1944. The rest of his life seems to have passed without incident. The couple had two daughters: Jean in 1941 and Valerie in 1948. Harrison continued to play cricket, appearing regularly for Kidderminster in the 1950s, but otherwise attracted no further attention from the world at large. He died on 28 May 1998, without an obituary appearing in Wisden; Margaret died in 2012.

Perhaps Harrison’s disappearance and his reasons for turning professional were connected in some way; it is equally possible that cricket played no part. But it is almost certain that he would never have played first-class cricket but for his background and the policy at many counties of playing amateurs at all costs. Without that desperation, we would not today know the unusual stories of men like Moss and Harrison.