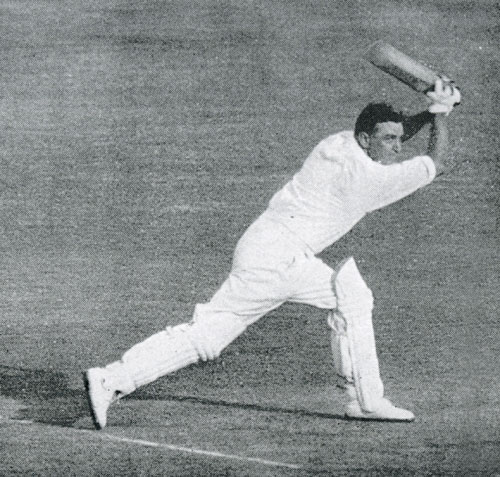

Portrait of Edwin Diver from his interview in Cricket: A Weekly Record of the Game, 21 December 1899

On 26, 27 and 28 April 1886, during Easter Week, a fairly unremarkable early-season cricket match took place at the Oval between Surrey and Gloucestershire. Surrey dominated and won by five wickets. But the scorecard conceals an unusual occurrence. Two former amateurs, Gloucestershire’s Walter Gilbert and Surrey’s Edwin Diver, were by coincidence both making their first appearances as paid professional cricketers. Neither man had an especially impressive match, although Gilbert took three wickets in one over, while Diver shared a fifty-run partnership with Bobby Abel, who scored a century. But their performances were a side-note as most of the interest in the game came from their almost unprecedented conversion from amateur to professional.

Walter Gilbert’s first-class professional career began and ended with this match. Before Gloucestershire played again, he had been arrested for theft and, after completing a 28-day sentence of hard labour, moved to Canada to begin a new life away from the scandal that brought his time in English cricket to a close. His spectacular fall has been written about several times.

Far less well-known is the story of Edwin Diver, the other debutant professional in that Surrey v Gloucestershire match. Diver was seven-and-a-half years younger than Gilbert and had a much more successful professional career. Unlike Gilbert, whose decision to become a professional was a desperate final attempt to overcome crippling financial difficulties, Diver arrived via a gentler route. He soon became only the second player, after Richard Daft, to play in the Gentlemen v Players match as both an amateur and a professional. And despite his switch of status, he remained highly regarded by the cricketing establishment – when he died, a generous obituary appeared in Wisden. However, Diver’s career came to a slightly untidy conclusion for reasons that are unclear.

Edwin James Diver was the nephew of Alfred Diver, a professional batsman who was a member of the first overseas team of English cricketers, which toured North America in 1859. Edwin’s father James was a college porter at Cambridge University; the family lived in various locations, so it is not clear at which college he worked, but they usually lived near Jesus College. Edwin was born in Cambridge a few weeks before the 1861 census, which records a midwife was still living with the family at their home on Upper Park Street. By 1871 the family, now living at Jesus Lane, could afford to employ a servant. Unlike the Gilbert family, there are no indications that they had financial problems.

At the time of the 1881 census, Diver was an Assistant Master at Wimbledon College in Surrey (although his name is almost illegible on the census return, it is certainly him). He had already established himself as a good cricketer. On one occasion, he scored 131 playing against his employers for the Stygians.

The Surrey team in 1885; Diver, then playing as an amateur, is standing at the back, second from the left

Working at Wimbledon College allowed him to qualify by residence for Surrey, for whom he played as an amateur from 1883. He averaged in the mid-20s in his first season, playing during the school holidays, and scored five fifties, respectable figures at the time. In his Wisden obituary, the editor Sydney Pardon recalled his early days with Surrey:

“He will always be best remembered on account of his short but brilliant connection with Surrey … A most attractive batsman in point of style, with splendid hitting power on the off side, his success was immediate. Indeed, he created such an impression that in the following year he was given a place in the Gentlemen’s Eleven against the Australians at Lord’s.”

In that 1884 game against the Australians, Diver batted very well when he came in to bat in the second innings with his team needing 45 to win having lost six wickets. He and AG Steel knocked off the runs without being parted. Further recognition came for Diver that season when he was selected for the Gentlemen v Players match at the Oval (although he scored a pair). It is clear that, at this stage in his career, he was starting to position himself among the leading amateurs in England. He never quite progressed though. In his obituary, Pardon wrote: “It cannot be said that Diver ever improved on his earliest efforts for Surrey, but he held his own, playing many a fine innings”. But in fairness to Diver, this may have been owing to what was happening off the field. Around this time, Wimbledon College went bankrupt, leaving him without an income. Diver, like many amateurs, was left struggling to afford a cricket career.

In The Players (1988), Ric Sissons details what happened next. In September 1884, the Surrey Committee made the rather unorthodox decision to pay Diver, still nominally an amateur, £2 per week throughout the winter “as long as he remains in the county”. In cricket terms, this paid off as he scored over 900 runs in 1885, including his first century for the county. In August 1885, Surrey gave him £75 to mark his “retirement” as he gave up cricket apparently to work in an office.

But in April 1886, Diver wrote to the Committee, saying that he was “heartily sick of office work and extremely fond of cricket but not having private means to allow me to continue to play as an amateur”. Therefore he asked to join the Surrey ground-staff as a professional; the Committee consented, although giving no guarantees how often he would play. Diver’s father was irritated, complaining to the Committee who replied to him that “no encouragement had been given to EJ Diver to become a professional.”

The Surrey team in 1886; Diver, now a professional, is seated third from the left

That season, Diver played 22 first-class matches, although he was less successful with the bat than in previous years. Nevertheless, he was selected once more for the Gentlemen v Players match at the Oval, this time for the professional team, making him one of the very few men to appear for both sides in this fixture, and only the second after Richard Daft.

However, this was Diver’s only season as a Surrey professional. Perhaps the wage paid by Surrey was not enough to make ends meet. But it also appears that he wished to continue working as a schoolmaster. When the season ended, he returned to Cambridge and opened his own school. Cricket wished him luck on his “return to his old vocation” and recorded that he had “taken premises in Trumpington Street”. Around this time, he also played with some distinction for Cambridge Victoria Cricket Club. He enjoyed a remarkable season in 1887: he scored 213 against Royston, then shortly after, in the space of a week, he scored 312 not out against St John’s College and 200 against Biggleswade. Some regret was expressed that Diver had been lost to first-class cricket.

But as recorded by Sissons in The Players, Diver continued to be associated with cricket. He later became the joint secretary and treasurer of Cambridgeshire County Cricket Club; Sissons does not say if this was a paid position, but it most likely would have been, which may suggest that Diver’s school was short-lived.

In 1891, Diver moved to Birmingham, where he played professional football for Aston Villa, appearing in three matches as a goalkeeper and seems to have remained on their books for three seasons. He also played cricket for Birmingham in the Midland League, although it is unclear whether he did so as an amateur or professional. Some clues about his status also appear in the pages of Cricket. In 1891, he played a first-class match for the South against the North; the scorecard omits his initials, indicating that he played as a professional. But at the end of the season, he appeared for “Eighteen of District” against “Eleven of Warwickshire” at Birmingham in a benefit match for AA Lilley. On this scorecard, he is given initials and so must have appeared as an amateur; Sydney Santall, another cricketer who played both as amateur and professional, played in this match as a professional.

In November 1894, Diver married Alice Beasley, the daughter of a publican, at Birmingham Parish Church; he listed his profession as “cricketer”. They had one child, Nora, in 1896 (although from what Diver said on the 1911 census, they may have had another child who did not survive and for whom there is no record). The couple managed hotels after their marriage, moving several times before settling at the Priory Hotel in Walsall.

The Warwickshire team in 1898; Diver is seated on the far right, his fellow amateur-turned-professional Sydney Santall is standing in the centre of the back row

Living in Birmingham eventually gave Diver a residential qualification to play for Warwickshire, for whom he played before they achieved first-class status. He resumed his first-class career as a professional with the county from 1894, although he only appeared a few times in 1895, the club’s first season in the County Championship. Diver was reasonably successful for Warwickshire from 1896, when he appeared more regularly. He was second in the county’s averages for 1896, but was fifth or lower from then until his career ended in 1901.

Diver had his best season in first-class cricket in 1899, passing 1,000 runs for the only time in his career. His only century came against Leicestershire, but this innings of 184 – out of a total of 276 – was his highest in first-class cricket. The runs came in 155 minutes and he reached his hundred before lunch on the first day. His reward for this form was to be selected once more for the Gentlemen v Players match at the Oval.

At the end of the season, Diver became the first professional to captain Warwickshire when no amateurs were available for their match against Essex at Leyton. As there were so many professionals, the Essex Committee permitted the Warwickshire team to use the changing room for visiting amateurs, but told them they could not use the amateurs’ gate, and instead must take a circuitous detour though the pavilion to use the side gate; they were also not permitted to sit in front of the pavilion. Contemporary reports reveal that two Warwickshire players pointedly refused to follow the instructions, using the amateurs’ gate to cheers from the crowd, and Diver protested to the Essex Committee. Sissons wrote in The Players that Diver went further and led the players along the boundary to enter the field by the amateurs’ gate, leading to a complaint from Essex, the home team. Contemporary reports do not mention this, but do suggest that there was some minor controversy over the events of the game. Sympathy was largely with Warwickshire, and Essex apologised for their treatment of the professionals.

A feature in Sporting Life in December 1899 following his successful season said that Diver claimed of his switch to professionalism that “amongst gentlemen the change made has not altered his position socially”. The article also reported: “At the present time Diver is highly respected in and around Birmingham, being the proprietor of one of the most flourishing hotels in the Midlands.” These two suggestions appear somewhat contradictory: it is hard to see that leading amateur cricketers of the time – men like CB Fry, Lord Hawke or FS Jackson – would have wished to associate with a professional cricketer who was running a hotel.

Diver was also interviewed for a feature in Cricket that December. The writer judged that “Diver’s cricket is of the kind which everybody likes to watch. He does not play a rash game, but on the other hand he never misses a chance of scoring, and while he is at the wickets it is a certainty that there will be some altogether delightful hits.” He commented that Diver hit especially hard on the off-side. Despite his experience in the Birmingham League, he considered that leagues were bad for first-class cricket; he also criticised slow play and defensive batting.

Diver had a poor season in 1900, and played just once in 1901, his final season in first-class cricket. But it is not exactly clear why his career ended as he had only suffered from one poor season and he played a good innings of 31 during his only appearance in 1901. There are a few possible explanations, but it appears the choice was his own and that he was not dropped. Perhaps outside interests prevented him playing more frequently: in October 1900 he had been elected President of Walsall Football Club, which may have taken up his time. He also may have needed to give more attention to his hotel. Or it is possible that increasing financial worries occupied his attention.

The 1901 census records him still as the manager of the Priory Hotel in Walsall, with a live-in staff of eight, plus his wife, daughter, and a relative of his wife. But this state of affairs did not last. On 12 November 1901, Diver disappeared without saying goodbye to his wife. The only clue she had came from a guest who told her that “Mr. Diver was seen at Queenstown to go aboard a boat bound for New York”. Supported by their brewery, Alice Diver applied to have the licence transferred to her name, which was approved in court. At the hearing, she explained that Diver was in financial difficulties; she also reported that she had previously managed the hotel during his absences through cricket and had great experience of managing public houses (presumably through her father). She stated that she had no intention of allowing Diver to return. By the end of February 1902, when the licence was permanently transferred to Mrs Diver, she had still not heard from her husband.

It appears that Warwickshire had not entirely given up on the notion that Diver could still play for them despite his disappearance, but an early-season issue of Cricket in 1902 listed him as “not likely to play” during 1902. Instead, Diver surfaced in Norfolk, where he played cricket in Hunstanton during the 1902 season. Shortly after this, he moved permanently to Wales. He played as a professional for Newport in Monmouthshire (Cricket reported that he scored 138 for the club in May 1903), and represented Monmouthshire in the Minor Counties Championship between 1905 and 1914. He also represented South Wales in matches against several touring cricketing teams, including Australian sides.

The only time Diver got in touch with his wife was to ask her to “intercede for him with his late employer” – presumably the brewery – and he never asked her to join him or offered her any financial support. These details emerged when Alice Diver applied for a divorce in early 1909 on the grounds of desertion, and adultery with Mrs Ellen Williams (whose maiden name appears to have been Salathiel) between 1905 and 1908. Williams, who supported Alice Diver’s claim, told the court that she had married a journalist called Samuel Williams who, it transpired, was already married and who then abandoned her. It was after this that she became close to Diver, and he “visited her” several times over the following years. The divorce, and custody of their child, was granted to Alice.

According to an article in the Folkestone Express, Sandgate, Shorncliffe & Hythe Advertiser (7 December 1910), Alice continued to have financial problems after the divorce. In 1909, she moved to Folkestone where she attempted to establish her own boarding house but business was never good enough to keep it running. By the end of 1909, she was heavily in debt and had to close the establishment; in late 1910, she was declared bankrupt and moved to Canterbury where she once more became manager of a hotel. On the 1911 census Alice, calling herself widowed, was visiting the Falstaff Hotel in Canterbury but was still listed as a hotel proprietor. By 1918, she had returned to Birmingham and was managing the Pitman Hotel: a report in the Birmingham Daily Post on 18 June recorded that she had been fined for not keeping an accurate register of food served, and exceeding the allowed amount of fat in meals. On the 1939 Register, she was still a hotel keeper, living in Hereford. She lived until 1959. Their daughter Nora married in 1921 and appears to have moved to Canada.

Meanwhile, in 1911, Diver was living alone as a boarder in Newport, listing himself on the census as a “professional cricketer and Ground Manager” at Newport Athletic Club. He remained as a coach at Newport until 1921, when he moved to Pontardawe near Swansea. Soon after, he died of heart failure, being found in bed on the morning of 27 December 1924. His obituary in Wisden, part of the same edition that reported Gilbert’s death, observed that “without realising all the bright promise of his early days, [he] played a prominent part in the cricket field for many years”.

Unlike Gilbert, Diver appears to have been happy to become professional and did not try to remain as an amateur through hidden payments, other than for a short time after he lost his job as a schoolmaster. He never seemed to believe it had brought disgrace upon him. And despite his “conversion”, he was remembered with affection by the cricketing world, as was clear from his Wisden obituary. Sydney Pardon even wrote the entry himself, a courtesy he did not extend to Gilbert in the same edition. Whatever circumstances ended Diver’s first-class career and caused him to leave his wife – and these may have been financial – he continued to play professional cricket and seems to have managed well enough in his later years. But if Gilbert lived happily in Canada with his family and in a respectable new job, perhaps Diver never quite achieved this peace. Instead he died alone in Wales.

By the time Gilbert and Diver died in 1924, few other amateurs had followed them by becoming professionals. CJB Wood had “converted” to a professional, but later reverted to amateur status. FR Santall, the son of Diver’s old team-mate Sydney, played for Warwickshire as an amateur from 1919 until 1923, then as a professional until 1939. But two examples in the later 1920s made a greater success of their conversion than either Gilbert or Diver.

Laurie Charles Eastman

by Bassano Ltd

whole-plate glass negative, 25 July 1931

NPG x150091

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Charlie Barnett (Image: Wikipedia)

Laurie Eastman and Charlie Barnett, two amateur-turned-professional cricketers who played in the 1920s and 1930s

LC Eastman, known to the cricket world as “Laurie”, played for Essex between the First and Second World War. Other than his cricket, little is known about Eastman’s life. He was the fourth child of John and Mary Eastman; his father was a tea merchant in London, although between the 1901 and 1911 censuses, he appears to have been reduced from an “employer” to an employed clerk.

During the First World War, Eastman received the Distinguished Conduct Medal and the Military Medal, but for reasons not made entirely clear in his Wisden obituary, the war ended his plan “to take up medicine as his profession”. Instead, he pursued an interest in cricket, making his debut for Essex as an amateur in 1920. In his first match, he took three wickets in four balls; in his third, he scored 91 batting at number ten against Middlesex at Lord’s. But these successes were not followed up, perhaps because, as his Cricketer obituary put it, his form was “adversely affected if the game was going against Essex”. Or in other words, he did not deal well with pressure on the cricket field.

Eastman played six times in 1920 and another six in 1921, presumably as he could not afford to play regularly. But from 1922, Essex followed the path taken by many counties to secure the services of amateurs with financial worries, and appointed him as their Assistant Secretary. From then on, he played regularly. After six years playing as an amateur, he became a professional from 1927, although there was little fanfare over this, and certainly none of the comment that followed the decisions by Gilbert and Diver in 1886. An aggressive batsman who often opened the batting, he was never a consistent performer. In 1929, he passed 1,000 first-class runs for the first time, a feat he repeated four times in the 1930s with his best return being 1,338 runs at an average of 32.63 in 1933. He never took 100 wickets in a season, his best being 99 in 1935, but generally took respectable numbers of wickets, first with medium-paced swing and later with spin. In the 1930s, he wrote several articles for newspapers in the 1930s without revealing too much or being in any way controversial. His career ended with the war in 1939, his benefit match being one of the last played. Injured by the force of a bomb while working as an Air Raid Warden, he never fully recovered and died after undergoing an operation in 1941.

Perhaps one of the most famous and successful “conversions” was Charlie Barnett. He was born in 1910, the son of a former Gloucestershire amateur who worked as a fish, game and poultry dealer. After being educated at Wycliffe, he first played for Gloucestershire as a 16-year-old amateur in 1927 and turned professional in 1929. In 1930, he married a widow who was 13 years his senior. According to his Wisden obituary, “Barnett retained a certain amateur hauteur in his cricket and his life; the supporters knew him as Charlie, but he always regarded himself as Charles. In the dressing-room he became known as The Guv’nor.”

Barnett was an extremely aggressive opening batsman and serviceable medium-paced bowler good enough to play for England in 20 Test matches. He made his debut in 1933, toured Australia for the 1936-37 Ashes series and scored 99 in the first session of the first Test of 1938, reaching his century from the first ball after lunch. Interestingly, on the 1939 Register, he listed himself not as a professional cricketer but as the manager and proprietor of a fish, game and poultry dealer. He briefly played for England after the war, and retired from first-class in 1948 when he went to play as a professional in the Central Lancashire League.

Unlike other ex-amateurs, we know more about Barnett as he lived until 1993 and was a frequent interviewee in later years, not least on the subject of Walter Hammond. And in many ways, he seems to have been an almost stereotypical amateur type; his Wisden obituary concluded:

“In retirement, he ran a business in Cirencester. A journalist called him a fishmonger. He wrote an indignant letter, saying he supplied high-class poultry and game, not least to the Duke of Beaufort. He maintained his amateur mien: he lived like a squire and hunted with the Beaufort and the Berkeley Vale, always, so it is said, with the uncomplicated verve he displayed at the crease.”

David Foot, in his 1996 book Wally Hammond: The Reasons Why had this to say:

“In the dressing room … Barnett was known as The Guvnor. This was because he’d been to a public school, had a better voice and more authority than most of the committee, and usually won an argument when he went striding in – on behalf of fellow pros with a legitimate grievance – to take on the county club’s management. He didn’t have a great sense of humour and was inclined to be bumptious … [He was] a Gloucestershire man of some social status who was not ashamed to play cricket as a professional … [He] lived in a fine Georgian house, hunted twice a week with the Beauforts and the Berkleys and didn’t stand any nonsense from anyone. The other pros very much respected him”.

But for all his impact, Barnett may be better remembered now for his abiding hatred of Hammond, with whom he had once been close. David Foot’s Wally Hammond: The Reasons Why contains a lot of Barnett’s views of his former captain. Even in the kindly hands of Foot, Barnett’s venom comes through; not a little of it appears to have been a slight sense of superiority, but his main grievance appears to have been how Hammond abandoned his first wife to have open affairs, and his unwillingness to play in Barnett’s benefit match in 1947.

Hammond himself famously switched from being a professional to become an amateur and captain England. But, overlooked by many, he actually began his career as an amateur, playing a few games for Gloucestershire in 1920 before signing professional forms for the following season. Hammond was not alone in switching from professional to amateur. Lancashire’s Jack Sharp did so, and subsequently became both Lancashire captain and a Test selector; Vallance Jupp likewise became captain of Northamptonshire after assuming amateur status. Warwickshire’s Jack Parsons went from professional to amateur, back to professional and finally became an amateur again. But perhaps these are stories for another time…