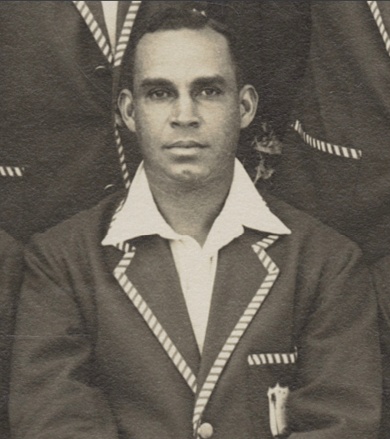

Frank Martin (Image: State Library of South Australia)

The first two men to score Test centuries for the West Indies were Clifford Roach and George Headley; both received great acclaim in later years when the West Indies had become the best team in the world. The latter in particular was revered as one of the greatest batters of all time. The third centurion for the West Indies had a more modest career, but played a crucial role in the first overseas win by the West Indies. In the final Test of a gruelling tour of Australia in 1930–31, having lost the first four games in the series, the West Indies managed a tense victory assisted by helpful conditions and two daring declarations. Headley was the key figure with a dominant century in the first innings and 30 runs in the second. But playing a much more defensive role, Frank Martin scored 123 not out and 20. He also took crucial wickets, recording match figures of four for 111 in 45 overs, including the vital one of Stan McCabe to end a partnership that threatened to win the game for Australia in the fourth innings. Yet few people today remember Martin. It did not help that he played alongside some famous names — Headley, Roach and Learie Constantine — as well as cricketers who were very well respected at the time (albeit similarly forgotten today) such as George Francis and Herman Griffith. Nor was Martin ever a player who would draw the crowds; his value lay in his dependability and calmness in a crisis.

Frank Reginald Martin was born in Kingston, Jamaica, on 12 October 1893. Little is known about his early life except that his father’s name was George Alexander Martin. He attended Jamaica College, where he performed well academically. At some stage, he worked an assistant in the Registry of the Collector General’s Office. In 1921, by which time he was working as an accountant, Martin married Myrtle Elise McCormack, with whom he had two children: Rona Dorothea Martin (born in 1924) and Frank Reginald Martin (born in 1926). By the time his children were born, Martin had begun to work as a clerk with the United Fruit Company, a job he continued for many years. When he twice visited England with the West Indies cricket team, travel documents listed him as a clerk (in 1928) and a cashier (in 1933).

Only vague details are available about Martin’s early cricket. He played for Melbourne Cricket Club in Jamaica, but he did not have the opportunity to play at a higher level for a long time. No first-class cricket was played in Jamaica between 1911 — when an MCC team toured the Caribbean — and 1925, when Barbados visited to play three matches. By the time of the latter tour, Martin was among the leading players in Jamaica and he was selected as an all-rounder batting at number four. Against the extremely strong Barbados team — undefeated in the Intercolonial Tournament played between Barbados, Trinidad and British Guiana since 1910 — Martin scored 195 out of Jamaica’s 411 for eight declared, therefore recording a century on his first-class debut. He was less effective with the ball, bowling 26 wicketless overs as the visiting team demonstrated their batting ability in a reply of 426 for two as the match was drawn.

Martin was less successful in the other two games, and failed to take a wicket (although he bowled only nine overs in each match), but Jamaica just about held on, and both games were draws, albeit favouring Barbados. But Martin had been able to demonstrate that he could succeed at first-class level, and retained his place when a strong MCC team played three first-class matches against Jamaica in 1926. He scored 66 in the first game (as well as taking four for 44 in the second innings), 44 in the second and 80 in the third. His success against English teams continued in 1927, when against a touring side led by Lionel Tennyson, the former England captain, he scored an unbeaten 204, at the time the highest innings for Jamaica in first-class cricket . He was also used as a left-arm spinner; although he took few wickets, he was generally economical (for example in the match in which he scored a double century, he had figures of 35–15–36–0 in the first innings). And when another team by Tennyson visited Jamaica the following year (when George Headley surpassed Martin’s record by scoring 211), he scored an unbeaten 65 in the first match, while in the third his scores were 63 and 141 not out.

By the time of the final games on that tour, Martin was occasionally opening the batting, but he often batted at number four or lower. In his 65 not out, he batted at number nine. Part of the reason for his variable batting position was the nature of his job with the United Fruit Company. He generally did not take time off for cricket, but had an arrangement by which he would work in the mornings before a cricket match. If the team was batting first, he would stay at work until the lunch interval unless the captain telephoned him because wickets had fallen early. In that case, he drove to the ground (usually he was already wearing his cricket whites) so that he could bat if required.

Martin was one of the most reliable batters for Jamaica, particularly before the emergence of Headley. A left-hander, he batted patiently and had an excellent defence, although he was able to punish any loose deliveries. As a slow bowler, he often delivered long accurate spells while other bowlers rotated at the other end. He was regarded as a good fielder, particularly to his own bowling, and a good runner between the wickets. He was also one of the key advisors to the Jamaican captain, Karl Nunes. From 1926 until 1947, he was also one of the selectors for Jamaica. But his reputation as a “stonewaller” meant that there was some criticism of his play; he was sensitive to complaints that he scored too slowly. One lifelong friend recalled in an obituary how Martin once showed him a chart of his scoring rates that proved he was “always ahead of the clock” in scores of 25 or more.

The West Indies team that toured England in 1928; Martin is standing fourth from the left in the back row

For all these concerns, Martin was a certain selection for the 1928 tour of England by the West Indies team. Followers of cricket in the West Indies (and in England) hoped that the visitors would build on their impressive 1923 tour, and an equally effective display against the 1926 MCC team that toured the Caribbean. Owing to the growing reputation of West Indian cricket, the team had been awarded Test status and the 1928 tour would incorporate their first matches at that level. As one of the most solid batters in the Caribbean, and with the possible advantage of being a left-hander, Martin had the potential to shore up a batting line-up that was heavy with stroke-players, and was familiar with the team captain, his fellow Jamaican Karl Nunes. But there were problems with the selection of the team: Nunes was not a universally popular choice as leader and when the first-choice wicket-keeper George Dewhurst withdrew from the tour, the captain was forced to take the gloves full-time; and because Victor Pascall, a successful member of the 1923 team, had lost form through a combination of age and illness, the team lacked a proven spinner. It was hoped that Martin could fill that particular breach, but he had never been a front-line bowler.

Previews of the tour identified Martin as good batter. For example, The Cricketer described him as: “A left-hander whose batting may well prove to be a feature of the coming tour. Can hit well and has strong defence.” He largely justified such predictions, but the tour was a disaster for the West Indies. The three Tests against England were each lost by an innings, and the batting proved completely unreliable, particularly against spin. Martin was one of the few to enhance his reputation. He took time to find his form, and scored just one half-century in the first month of the tour, but innings of 56 against Ireland and 81 against the Minor Counties got him going in June. He scored a non-first-class century against the Civil Service, fifties in consecutive matches against Lancashire and Yorkshire, and towards the end of the tour scored 165 against Hampshire and 82 against Kent. He was fairly consistent — he reached double figures 32 times in 46 first-class innings — even though Nunes (perhaps aware of his versatility because they played together for Jamaica) constantly shifted Martin’s batting position. He most often opened or batted at number three, but there seemed to be no settled plan, which perhaps reflected the unreliable nature of the team’s batting.

Martin run out for 21 in the second Test against England at Manchester in 1928; A. P. Freeman can be seen in the act of throwing the ball from mid-on. The other batter was Clifford Roach and this misunderstanding began a collapse from 100 for one to 206 all out. (Image: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 28 June 1928)

Martin had one of the best batting records for the West Indies. In the Test matches, he was solid: although his highest score was only 44, he scored 175 runs in six innings at 29.16, which placed him at the top of the West Indies Test averages (among those who batted more than twice) and he was comfortably the leading scorer. In all first-class cricket, his final record — 1,370 first-class runs at an average of 32.62, with eight fifties and the one century — placed him third in the team averages, and he was the second-highest run-scorer (he was the leading run-scorer if non-first-class games were taken into account). He was less effective with the ball — 19 first-class wickets at 44.89 — but offered useful support to the main bowlers.

His statistical success was backed up by the positive impression he made on English writers. The Wisden review of the tour praised him: “Martin, a left-hander, was probably the most difficult man on the side to dismiss. He watched the ball closely, and played back very hard, while on occasion his steady left-handed slow bowling helped to keep down the runs. He had a happier personal experience in the Test Matches than any of his colleagues, being only once out for less than 20, and never for a single figure.” The Cricketer was similarly complimentary: “Martin and Roach, so far as the Test matches go, were the best batsmen. Martin is a very sound left-hander, with a good defence, strong on the leg side, and a cool head … Both these men appeared to play with far more confidence than the rest of their colleagues, with the exception of Constantine”.

However, J. N. Pentelow, writing about the tour twelve months later in Ayres Cricket Companion, said: “Martin was easily the most consistent bat on the side. He is nothing like what [George] Challenor was in 1923; but what had been said of his steadiness and imperturbability was fully justified. He would go on for hours playing the safety game, waiting for the easy one to hit. But a batsman of his parts should not do so much of the pendulum business. Time after time his bat met the ball, only to send it to the bowler or to mid-off. It would pay him to take more risk. Yet one is sure that in the game he played he was considering the interests of his side.” After listing Martin’s highest scores, Pentelow concluded: “But he ought to have made more.” Writing in Cricket and I (1933), Learie Constantine viewed Martin’s achievements more positively: “But if many failed [during the 1928 tour], certain men stood out as absolutely first-class cricketers. There was the calm superiority of Martin in county games and Tests, not a Challenor by any means but a master of defensive play.”

Martin had a quieter time when another English team — Sir Julien Cahn’s Eleven — toured Jamaica in 1929; he passed fifty just once. When another MCC team toured the West Indies in 1930, Martin only played in the final Test. This was not necessarily a reflection of his ability; for a combination of reasons, including a desire to keep down costs and a bias towards selections from the host nation, the West Indies selectors (which involved a different group of selectors for each Test) chose different captains for each Test and a total of 27 players in four Tests. When the MCC visited Jamaica, Martin scored an unbeaten 106 (in what transpired was his final appearance for Jamaica) and was picked for the final Test. In a high-scoring draw that had to be abandoned after nine days, Martin scored 33 and 24, although he took just one wicket in 54 overs.

The West Indies team that toured Australia in 1930–31. Back row: G. A. Headley, C. A. Roach, E. A. C. Hunte, F. I. de Caires, O. C. Scott, O. S. Wright, I. Barrow, E. L. St. Hill. Middle row: H. C. Griffith, L. N. Constantine, J. E. Scheult (assistant manager), G. C. Grant (captain), R. H. Mallett (manager), L. S. Birkett (vice-captain), F. R. Martin, E. L. Bartlett, G. N. Francis. Front row: J. E. D. Sealey (Image: State Library of South Australia)

Given his experience and his record for Jamaica, Martin was always a certainty for the West Indies team that toured Australia in 1930–31, even though he was 37 years old when it began. The tour was regarded as a success; although the playing record of the team was poor, they were popular with spectators and it was generally believed that they performed better than results indicated. Martin was not a success for the most part; The Cricketer considered him “disappointing”. He had several low scores in the early games, and when he did make a start, he was dismissed in the 20s and 30s. He did not reach fifty until the West Indies had been in Australia for over a month, and his unbeaten 79 came against a weak Tasmania team. Apart from a fifty against a “Victoria Country” team, he did not make another substantial score until hitting 56 in the return game against New South Wales in the penultimate match. By then, Australia had won the first four Tests (three by an innings and the other by ten wickets) without too much difficulty; Martin’s highest score had been 39. At times he was used quite heavily as a bowler, for example taking three for 35 in the first match against New South Wales, and bowling long spells in the first and third Tests. And in the fourth Test, he took three for 91 from 30.2 overs.

The visiting team had been surprised by the slow pace of the pitches in Australia, and as the tour drew to a conclusion, pleaded behind the scenes for something with more life so that they could play better cricket for the public. Coincidentally or not, the pitch for the final Test, played at Sydney, was faster and Martin finally found his form. Opening after the West Indies won the toss, he batted throughout the first day. He had George Headley had added 152 for the second wicket in 146 minutes, out of which Headley scored 105. Martin reached fifty from 96 deliveries in 102 minutes (with five fours), his first such score at Test level in his ninth game. But after that, he slowed down as Headley reached his century from 169 deliveries and faced most of the bowling. After Headley was dismissed, Martin played a similarly supporting role alongside his captain, Jackie Grant. Just before the close of play, Martin reached his century in 273 minutes from 288 deliveries (his second fifty had taken three hours and 192 deliveries) and finished the day on 100 not out, and the West Indies were 299 for two.

On the second day, he and Grant took their third wicket partnership to 110, out of which Grant scored 62. But rain fell to affect the pitch, and wickets fell rapidly. In this period, Martin excelled; Wisden noted: “He showed marked skill especially when the pitch was getting treacherous.” The increasingly sticky pitch prompted Grant to declare with the total on 350 for six; Martin was left unbeaten on 123 not out (after 347 minutes). He was quickly into the attack and in the helpful conditions removed Bill Woodfull and Donald Bradman before the end of play, when Australia were 89 for five. In easier batting conditions after the Sunday rest day, Australia recovered to 224 but still conceded a first-innings lead of 126. However, more rain again made run-scoring difficult and the West Indies struggled to 124 for five at the close of the third day. Martin had again opened, but could only manage 20 runs.

Frank Martin batting in the nets at the Sydney Cricket Ground in 1930–31 (Image: Wikipedia)

Rain completely washed out the fourth day, and the prospect of further difficult conditions persuaded Grant to declare on the overnight total, leaving Australia needing 251 to win; because Australian Test matches were played to a finish, there was no time limit for Australia to score the runs, and this was the first time in an Australian Test that any captain had declared both of his team’s innings closed. Martin again struck early, removing Bill Ponsford, and Australia were soon 76 for six. But Alan Fairfax and Stan McCabe added 79 for the seventh wicket; Martin had McCabe caught, but runs continued to come and the touring team became a little nervy before the last man was run out to give the West Indies a 30-run win. It was their first overseas victory in a Test match and when combined with the teams win over New South Wales in the immediately preceding match meant that the tour ended well, and the result was acclaimed both by the Australian crowds and back at home in the Caribbean.

Martin ended the tour with 606 first-class runs at 27.54 and 21 wickets at 45.23. In the Tests, he scored 254 runs at 28.22 and took seven wickets at 64.00. But the match at Sydney was his final Test. After the tour, when he had returned home, Martin announced (at a dinner given by the Jamaica Cricket Association in honour of the Jamaican members of the touring team) that he felt he had to retire from representative cricket. Stating that his employers, the United Fruit Company, had been very generous in allowing him time off to tour, he felt that he owed it to “give them of his best services without interruption.” Therefore when another team organised by Lionel Tennyson visited Jamaica in 1931–32, Martin was absent.

Nevertheless, he was not quite done and would probably have played more Tests but for injury. After what was likely some behind-the-scenes negotiations, he was chosen for the West Indies team that toured England in 1933. As he was 39, his selection was not universally popular and in some quarters he was described as a “has-been”. A preview in The Cricketer noted that his selection had been a surprise but noted his steadiness and ability on the “big occasion”, although it was critical of his fielding. He began the tour steadily, and scored a first-class fifty against Oxford University. But when playing against Middlesex in early June, he suffered a leg injury while chasing the ball. It was so serious that he was unable to play again on the tour, and therefore that match was his final appearance in first-class cricket. His absence affected the balance of the team, and Wisden noted: “The loss of such a valuable all-round man could not fail to be very severely felt.” C. L. R. James, writing in the Manchester Guardian at the end of the 1933 season, suggested that Martin’s absence made the team vulnerable to collapse and meant that there was no-one to counter the leg-spin bowling and slow-left-arm bowling against which the batters generally struggled.

Nevertheless, Martin remained with the team until the end of the tour (he acted as the team scorer in at least one match) and as had been the case on the 1928 tour was joined by his wife towards the end; they travelled home together with the rest of the side.

Martin’s final career figures were respectable: 3,589 first-class runs (at 37.77), 74 first-class wickets (at 42.55), 486 Test runs (at 28.58) and 8 Test wickets (at 77.37) in nine matches for the West Indies. In 15 matches for Jamaica, he scored 1,262 runs at 70.11, including four centuries (with one on each of his first and last appearances for the team).

The rest of his life was lived away from the spotlight; a friend called him “reticent and quiet”. When discussing cricket, he always advised people to “play their natural game”. He continued to work for the United Fruit Company, and later founded the Unifruitee Senior Cup Club cricket competition. Little else is known of him or his life. His wife died at the age of 57 in 1950 of arteriosclerosis and cerebral thrombosis. Martin died in Kingston in 1967, at the age of 74, from a coronary thrombosis. There is probably a lot more that could be said of him, but like so many of his contemporaries in the West Indies, he remains a mystery except in his achievements on the cricket field.