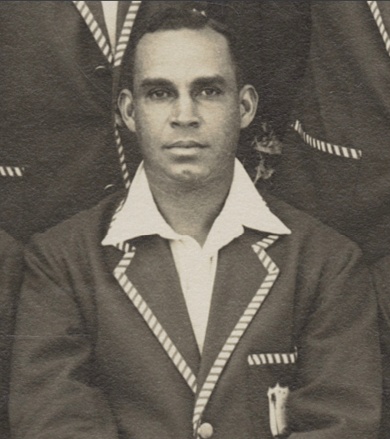

Errol Hunte in Australia in 1930 (Image: National Library of Australia)

Early West Indian Test cricketers are poorly served by historians; many are little more than a name on a scorecard. Such a fate is perhaps inevitable for almost anyone who played so long ago unless they were from England or Australia, but even so there are many cases from the Caribbean in the period before the Second World War. One of the more extreme is the Trinidadian wicket-keeper Errol Hunte. He played three Tests in 1930 and toured Australia in 1930–31, but his Wisden obituary was just a few bland lines. To measure it in a different way, his Wikipedia article is one sentence at the time of writing. His biggest claim to notability was that for many years, Wisden confused him with another player and split his Test appearances with the unrelated R. L. Hunte of British Guiana, a simple case of mis-transcribing “Errol” as “R. L.”, an error uncorrected until 1967. Gideon Haigh wrote about this mistake for ESPNcricinfo in 2006, but even he had little to say about the player himself. Perhaps it is time to redress the balance a little.

Errol Ashton Clairmonte Hunte was born in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, on 3 October 1905. Almost nothing is known about his early life except that in the 1920s he played for Maple Cricket Club in Trinidad. In Beyond a Boundary (1963), C. L. R. James — who also played for Maple — C. L. R. James described it as the club of “the brown-skinned middle class”, which might give some clues about Hunte’s background. Hunte’s first appearance in the record books came when he played for North Trinidad against South Trinidad in 1925; two years later, he played for the North against the South once again, this time in the Beaumont Cup, when one of his team-mates was C. L. R. James, and then again in 1928. He did not distinguish himself with the bat in any of these matches, although he was playing alongside some of the biggest names in West Indian cricket (there is no indication of whether he kept wicket in these games, but it is most likely that he did). In May that year, when some of those names were taking part in a very undistinguished tour of England that incorporated the first Test matches played by the West Indies, Hunte and his fellow Trinidadians Edwin St Hill and Ben Sealey visited New York as part of a West Indian cricket team. The sailing record provides some of the only information we have about Hunte: that he was a teacher; that he was unmarried and lived with his father, T. W. Hunte, in Belmont; and that he was 5 feet 11 inches tall.

The following January, Hunte made his first-class debut for Trinidad, playing as the wicket-keeper against Barbados and British Guiana as his team easily won the Intercolonial Tournament at home. But Hunte’s highest score in three innings was 26, and his selection reflected the somewhat confused nature of Trinidad’s team in this period following the mysterious withdrawal of the team’s regular wicket-keeper George Dewhurst from first-class cricket. Hunte was one of several wicket-keepers tried in this period. If his batting made no impact, he must have impressed to some extent with the wicket-keeping gloves. He retained his place when the team defended their title later in the year in British Guiana (playing once more for North Trinidad in the meantime) but again achieved little of note (batting at number ten in both innings, having appeared in the middle order in his first two matches).

The West Indies team for the first Test in 1930. Back row: (Unknown), (Unknown), Edwin St Hill, Clifford Roach, Frank De Caires, Leslie Walcott, Errol Hunte, (Unknown). Front row: James Neblett, George Headley, Learie Constantine, Teddy Hoad (captain), Cyril Browne, Derek Sealey, Herman Griffith.

But either his wicket-keeping shone, or he had batting success in local Trinidad cricket because not only did the Trinidad selectors stick with him, he was chosen as the wicket-keeper for the West Indies in the opening Test match for England’s tour in 1930. Nor did his selection owe anything to regional politics because his debut was in Barbados, meaning that the Barbados selectors must have judged him to be the best wicket-keeper. In a drawn game, he batted at number eleven and scored 10 not out and 1. However, a gossipy article a few weeks later in Trinidad’s Sporting Chronicle suggested that he had not impressed the cricket authorities in Barbados, an opinion echoed in The Cricketer’s review of the tour published in England.

When the series moved to Trinidad, Hunte became (presumably inadvertently) caught up in a mysterious controversy involving the former Trinidad captain and wicket-keeper George Dewhurst, who had withdrawn from the West Indies team that toured England in 1928 over selection issues and not played for the island since. However, with the visit of the English team, there were moves afoot not only for Dewhurst to return to the Trinidad team, but also to captain the West Indies for the Trinidad Test. As was normal practice, the MCC team played two matches against Trinidad before the Test match. In the first, the home team were captained by Nelson Betancourt, a 42-year-old who had played intermittently for Trinidad since 1905 and had a very undistinguished playing record. The wicket-keeper for this match was Hunte, who batted at number eleven in the first innings, scoring 12 not out, and 20 not out (when he cannot have batted last, but his position is not known) in the second as Trinidad won by 102 runs. For the second game against the MCC, Hunte was replaced by Dewhurst, who also captained the team in what was regarded by some elements of the press as a trial to see who should captain the Test team. Several newspapers predicted that he would be named as captain, but when the team was announced, Betancourt was captain and Hunte had been retained as wicket-keeper.

Given his lack of batting form, it is remarkable that Hunte was asked to open he batting alongside Clifford Roach, and even more remarkable that he scored 58, his maiden first-class fifty. His half century came in 102 balls with eight fours, and he shared a second-wicket stand of 89 with Wilton St Hill (after Roach was dismissed without a run scored). Wisden noted that he and St Hill “played steadily”. He scored 30 in the second innings, sharing an opening partnership of 57 with St Hill. West Indies lost that game but Hunte, having impressed in the role and with his batting, was retained as wicket-keeper when the teams travelled to British Guiana. He once again opened the batting and this time shared an opening partnership of 144 with Roach; he scored a dogged 53, reaching his half century from 195 deliveries. Nevertheless, he had a great deal of luck; Wisden observed: “MCC’s [England’s] fielding was badly at fault when West Indies opened their first innings with a stand of 144, Hunte being missed four times.” Hunte was first out, and Roach went on to a double century. Hunte scored 14 in the second innings and West Indies won by 289 runs.

Hunte did not retain his place for the final Test, played in Jamaica, making way for the local wicket-keeper Ivan Barrow. But he had impressed some critics. The review of the tour in The Cricketer stated of Hunte: “An ungainly wicket-keeper, but active and effective. Kept very moderately in Barbados, but very well in Trinidad. Proved himself a most useful opening batsman, having a very stubborn defence. He can also hit the ball hard. Ugly and ungainly in this department too.” In Trinidad, the Sporting Chronicle viewed him as an “able” keeper who showed “high promise” with the bat. But Wisden became very confused; Hunte was listed in the averages as two separate people. His debut was listed as a cricketer called “E. Hunte” but the other two appearances were attributed to “R. L. Hunte”, and this mistake was perpetuated in later editions of the almanack, which recorded one Test appearance by E. Hunte and two by R. L. Hunte. The reasons are not hard to find: Wisden seemingly had no correspondent on hand and, compared to The Cricketer, displayed patch knowledge of West Indian cricket. As there was a cricketer in the Caribbean called R. L. Hunte (Ronald Hunte, who had a twenty-year career with British Guiana), the confusion of the initials with the name “Errol” is understandable but inexcusable in a publication concerned with statistical accuracy. The mistake was not corrected until the 1967 edition of Wisden.

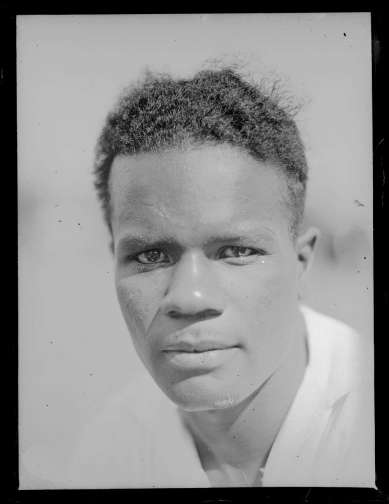

Left to right: George Headley, Derek Sealy and Errol Hunte in Australia in November 1930 (Image: National Library of Australia)

Given his success with bat and gloves, it was inevitable that Hunte would be selected for a tour of Australia in 1930–31. He and Barrow were the main wicket-keepers (although Derek Sealy kept wicket later in his career and could have filled in), but the suspicion was that Hunte was chosen as much for his batting as wicket-keeping; for example, the Daily Gleaner in Jamaica suggested: “Anyhow Hunte as a good opening batsmen may be played more in that capacity than for his keeping qualities.” If so, he was picked based on a very limited record. Furthermore, there were some doubts about his health going into the tour; the Gleaner reported that he had been “a trifle seedy”. Yet he must have recovered because in later years, the doctor responsible for the health of the team on tour told Andy Ganteaume that Hunte was “the finest specimen of a man” he had seen.

The Australian press showed considerable interest in the team, particularly the black players. A tour preview in the Adelaide Advertiser, written by Thomas D. Lord of Trinidad, gave a brief summary of Hunte’s career and described him as an excellent wicket-keeper and worthy successor to Dewhurst. It also stated of his batting: “He is endowed with great patience and concentrates on a sound defence but when once he sees the ball well, he hits hard.” Another oddity about Hunte’s tour was that he was advertised in Sydney’s Daily Pictorial as an aspiring author: “Hunte has a remarkable flair for literature, and he has written a vivid human drama specially for the “Sunday Pictorial.” The story duly appeared on 30 November, called “The Soul’s Awakening”

Whatever the literary merits of the story, Hunte’s tour on the field was undistinguished. His highest score in five first-class matches was 29 and although he was given several chances to establish himself, Barrow was the favoured wicket-keeper throughout the tour and played all five Test matches. The Cricketer review of the tour noted that “wicketkeeping [was] a weak-point for some time with the West Indies” and that Barrow had been played in the Tests. However, during the tour an article in the Trinidad Sporting Chronicle suggested that Hunte had been left out following an incident in a match against Queensland. According to the article, Hunte “with great show and confidence appealed for a catch” at the wicket when Victor Goodwin was batting. The appeal was turned down and Hunte “proceeded to make demonstration in seeming disgust” and threw the ball away. The article suggested that “on account of this and other similar reasons”, Hunte was omitted from the Tests. The newspaper concluded that “Hunte should not have taken this sort of local Savannah Cricket habit to Australia” and felt “pretty sure that his inability to accept decisions against his appeals in the proper manner and his all too demonstrative yet not always safe methods when performing behind the wicket have been responsible for the small number of his appearances in the big matches.”

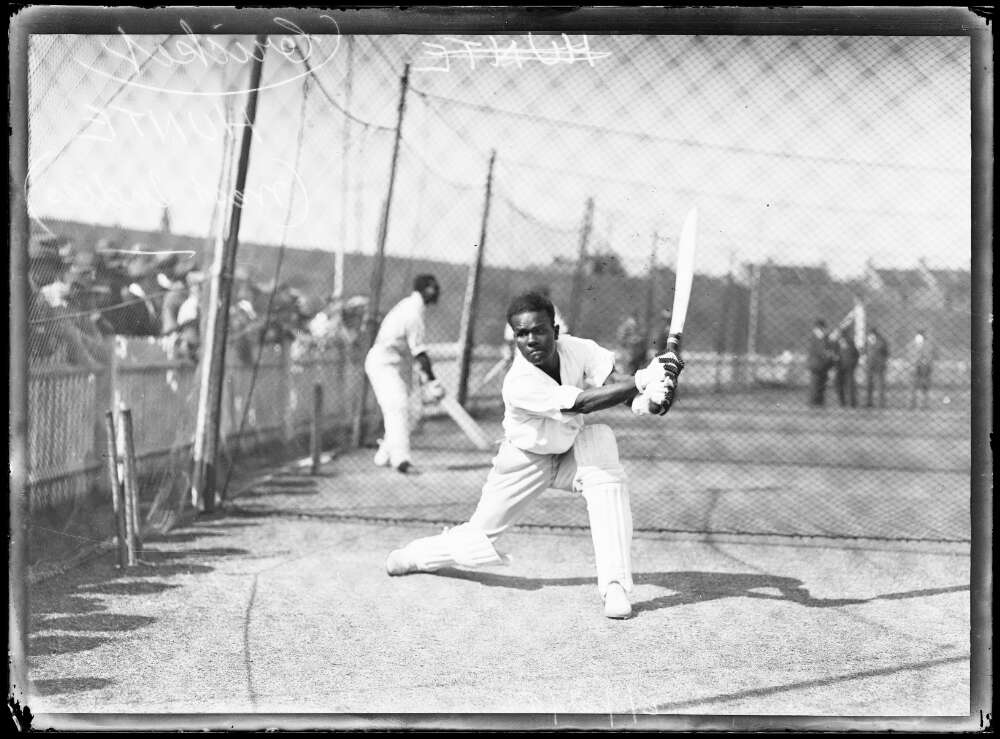

Hunte batting in the nets at Sydney in 1930 (Image: National Library of Australia)

This account was denied by the batter Frank Martin when he returned home to Jamaica. In a speech at a dinner to honour the Jamaican cricketers who played in Australia, Martin was critical of the Sporting Chronicle for printing the article and mildly rebuked the Gleaner for reprinting it. He said that he was sure “that the intelligent public, knowing the source from which that article came, would not, or did not place any credence to it.” He called Hunte “a fine fellow” and a “sportsman”, for whom such actions would be “quite foreign”. He said that no such incident took place and that the story was “only a crude way of excusing the exclusion of Mr Hunte [who] was excluded from the team because Mr Barrow proved himself a very good keeper.” The endorsement of Hunte received a warm reception from his Jamaican audience.

Even if there was no truth in the rumours, Hunte never played for the West Indies again. His name was discussed prior to the 1933 tour of England, but a writer for the Port of Spain Gazette said: “I understand that there is prejudice against Errol Hunte. In fact I know there is. The quicker the selectors put this behind their backs and think of nothing else but the success of the side the better for them. For Hunte is not only a proper wicket-keeper but a good batsman with a fair experience and where so much is uncertain it is best that the side should have as many batsmen as possible.” As was the case in 1930 and 1930–31, there is a definite sense that Hunte’s selection was tied up in matters beyond the field, even if we cannot be too sure what they were. But when he failed in a trial match for the tour, he was omitted from the team. An account in The Cricketer stated: “Hunte and De Caires both visited Australia and both failed as batsmen in the trials; indeed, C. L. C. Bourne kept wicket in the former’s place and he perhaps never had more than an outside chance.”

Hunte retained his place as Trinidad’s wicket-keeper for the 1932 and 1934 Intercolonial Tournaments (there was no tournament in 1933, with games instead arranged to inform selection for the 1933 tour of England). His highest score in these games was 56, and after scores of 2 and 2 opening the batting against Barbados in 1934, his first-class career was over (although he captained South Trinidad in the Beaumont Cup as late as 1937). His role as Trinidad’s wicket-keeper was taken by Allman Agard.

Nevertheless it is likely that Hunte had chosen to make himself unavailable for financial or career reasons. By 1930, he no longer worked as a teacher but was instead a clerical assistant at a magistrate’s court in Princes Town and Moruga, on an annual salary of £110. And it seems that some time in the early 1930s, Hunte married (only the first names of his wife are known — Olive Leona — and we know that she was born in 1906) and in 1934 he became the father to twin girls. A son (1940) and another daughter (1942) came later. Perhaps he chose to concentrate on his career in order to support his family.

He certainly remained a civil servant in later years, and travelled extensively. For example, he visited New York (with his wife) in 1949. But he and his family also spent some time in England. In 1954, he spent time in England working for the British Council in Liverpool, accompanied by his wife and four children; his eldest daughters were working as a civil servant and as a librarian. Hunte stayed for several months, living in London. In 1960, he spent six months in England, working as a civil servant at the Colonial Office in London. And in between these extended visits, he also spent time as a delegate at the conference on Local Government at the University College of the West Indies in 1957.

But he was not done with cricket and worked as a government coach in a scheme organised by the Ministry of Education and Culture. He became head of the Community Development Department and worked alongside several former West Indies cricketers included Ellis Achong and Andy Ganteaume. In his 2007 autobiography, the latter wrote: “Errol was one of the finest gentlemen one could ever meet. Errol was an exceptional individual. He had a very pleasant manner, a lovely sense of humour, was also a good billiards player and an outstanding card player who was always able to avoid any unpleasant exchange with any other player.”

Hunte died of a cerebral haemorrhage in 1967, leaving an estate worth £1,565. His final address was D8 Empire Flats, St Vincent Street, Port of Spain. His probate was handled in England two years later. He had a brief obituary in Wisden, which even if it had corrected his misidentification as R. L. Hunte, made another mistake, saying that he played for British Guiana (again, probably a confusion with the real R. L Hunte). It called him a “good opening batsman”. Hunte’s obituary in The Cricketer went the other way, and called him (perhaps a little generously) “an outstanding wicket-keeper in intercolonial cricket”. But as was the case with so many of Hunte’s contemporaries in the West Indies teams, there was little interest in going any further. Yet in many ways, his cricketing career and his life in general are perfect illustrations of West Indies cricket in the early 1930s: a combination of good fortune, the effects of politics (through no fault of his own) and — despite the obstacles — some very good cricket before real life intruded.