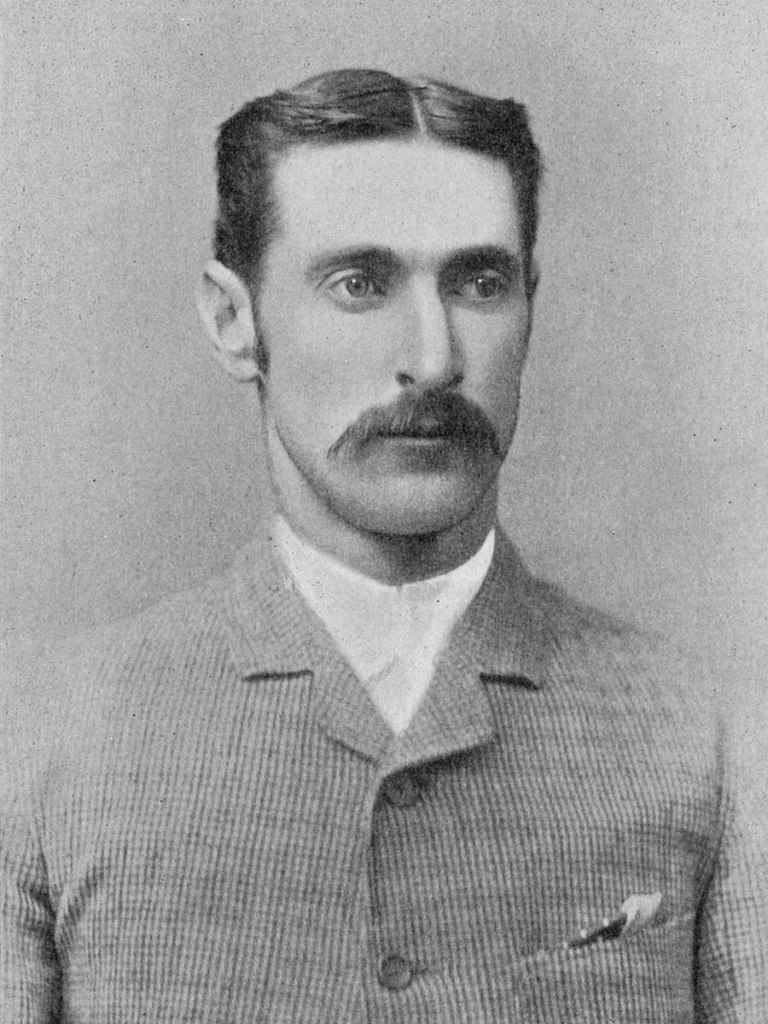

Fuller Pilch in 1852 (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Anyone who ventures into a forum for cricket fans, or browses the cricket sections of Reddit will be familiar with the sometimes bitter and rancorous arguments over who were the greatest players of all, and the related debate regarding whether cricketers of today are better or worse than those of earlier times. Is Virat Kohli is better than Sachin Tendulkar? Is Jimmy Anderson the greatest English bowler of all time? Was cricket better twenty years ago? Or thirty years ago? Or forty years ago? The answers to these fraught questions often depend on who is asking, but discussion can — and often does — become heated very quickly. As ever, this apparently modern phenomenon is nothing new; tension between past and present has been a feature of cricket since its very earliest days. It is perfectly illustrated by changing opinions on Fuller Pilch, the best batter in the world from the 1820s until the mid-1850s. When he emerged, he was merely viewed as a successor to William Fennex. By the time he retired, he was regarded as the greatest player of all time and the originator of the whole style of “forward play”, especially the forward defensive shot. And within fifty years, he had become a lightning rod in the debate between those who thought cricket (personified by W. G. Grace and his scoring feats) had improved since Pilch’s time and those who thought it was not the sport it used to be.

Perhaps the only difference between modern debate and the case of Pilch is that when he was at his peak, no-one seriously questioned his greatness and most writers believed he was the best batter to play the game. While his first-class batting average of 18.61 might appear underwhelming, it was one of the best of the period in which he played, when wickets were uniformly difficult. Earlier players might have boasted better statistical returns —William Beldham, who played from 1787 to 1821, averaged 21.47 in matches that modern historians have adjudged first-class; Frederick Beauclerk averaged 24.96 between 1791 and 1825 ; William Lambert averaged 27.65 between 1801 and 1817 — but these players faced lob bowling in a period when run scoring became much easier as batting equipment and technique improved. The introduction of round-arm bowling, often delivered at a pace which had never been previously encountered, meant that scores and averages plummeted from the 1820s, just as Pilch began to establish himself. Therefore, there was little doubt in the mind of his contemporaries that Pilch raised batting to a point which had never been reached before.

An illustration of a cricket match at Lewes in 1816, from a book by William Lambert (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

In many ways, the game that Pilch played was completely different to that played by Beauclerk or Beldham or Lambert. And it was just as dissimilar to the modern sport, making direct comparisons impossible. He played an astonishingly long time ago in cricket terms; his “first-class debut” (which to his contemporaries would merely have been his first appearance in a major match) was over 200 years ago, and he was at his peak before Victoria became queen of England. In fact, he made his debut (at the age of sixteen) only seven months after the death of George III. For a little further context, the Napoleonic Wars only ended five years before he made his debut. And by the time he was signed to play for Kent in 1836, cricket had transformed through the legalisation of round-arm bowling (which had been the dominant form of bowling for some time, despite its official illegality). But overarm bowling was still thirty years from legalisation; pads and gloves were a rarity; there were no fours or sixes because all hits had to be run on grounds without boundaries; and there was no county competition or even a recognised structure to the games played.

Fortunately for us, in this time cricket had also become the subject for books and newspapers and therefore we can begin to capture the high regard in which Pilch was held, and discern something about the technique which allowed him to succeed. Ironically, even this first cricket writing was often nostalgic, looking back to an idyllic past, such as John Nyren’s The Cricketers of My Time (first published in 1832 but republished various times afterwards), which was about players from the turn of the nineteenth century. The elegiac tone suggested that cricket was even then “not what it used to be”, but according to John Bruce Payne in the 1896 edition of the Dictionary of National Biography, Nyren (who died in 1837) “used to say that Pilch’s play almost reconciled him to round-arm bowling”.

Yet writers continued to hark back, and to help their audience comprehend the appeal of the old players, used Pilch as a comparison point. When James Pycroft published The Cricket Field in 1851, just as Pilch’s career was drawing to a close, referred to famous old players as being “as often mentioned as Pilch and [George] Parr by our boys now” and discussed men “who, at the end of the last century, represented the Pilch, the Parr, the [Ned] Wenman [a famous wicket-keeper contemporary to Pilch], and the [John] Wisden of the present day.” And there is just the slightest hint of the attitude that survives among old players to this day, that the modern cricketer was not as good, because Pycroft related how the old Hambledon player William Fennex used to claim that he taught Pilch to bat. Pycroft was not convinced though, and observed that “all great performers appear to have brought the secret of their excellence into the world along with them, and are not the mere puppets of which others pull the strings — Fuller Pilch may think he rather coincided with, than learnt from, William Fennex.”

Therefore, even Pilch was compared (and perhaps in the case of Fennex’s claim, not always favourably) with players who had come before. But his excellence also commanded examination. And, in that time long before video replays and the use of analysts, we can see that Pilch and his contemporaries were technically very astute and could adapt their games as required. For example Pilch — who later worked as a groundsman himself — was very aware of the need to tame the pitches on which he batted. His entry in the modern Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, written by Gerald Howat, states that when Pilch was playing for William Clarke’s All England Eleven, he “[took] his own scythe to cut some of the rough pitches encountered in matches against ‘odds’ up and down the land.” Although he often batted (in the style of the time) wearing a top-hat, when he was dismissed when a ball knocked the hat onto his wicket, he stopped wearing one. And he used a bat specially adapted with a short handle to favour his own batting technique.

But more interesting for the growing number of cricket writers was the way in which he batted. And in the latter half of his career, before his retirement in 1855, there was no doubt about his greatness. In 1844, the journalist William Dennison wrote in Sketches of Players that Pilch “as a bat, has been one of the brightest luminaries of the cricket world, during the last 20 years … There has been no man, having played as many matches, who has approached him in effectiveness and safety of style, or in the number of runs he has obtained. His vast length of reach and powers of smothering a ball by his ‘forward’ play, the brilliancy of his ‘cuts’ on either side of the ‘point’ and into the ‘slips,’ and the severity of the punishment he administers to the ‘leg,’ have all and each, over and over again, caused a spontaneous ebullition of applause to burst forth from the spectators in every part of the field whereon his feats have been displayed.”

Charles Box, in The Cricketer’s Manual (1848), said quite a lot about Pilch. He noted how in one game, a journalist wrote of his sympathy for the Nottinghamshire fielders on a hot day as Pilch scored 61 not out for Kent: “Pilch took his place at the stumps, as usual, as the third man, and at the third ball wrote down three with a leg hit. But what of this — threes, fours, and fives appear as easy for him to get, as ’tis for us to write about them.” During the innings, “he was despatching the ball to the extreme limits of the ground, at all points of the compass, just when, where, and how he pleased”. The author jocularly observed: “All attempts to get him out were as futile as the endeavour to catch a leviathan with a lady’s reticule, or to pull the sun out of heaven with a silken halter.” He added, none-too-seriously: “We denounce Pilch as a ‘merciless tyrant,’ when at the wicket.” Box himself wrote admiringly: “As a batsman Pilch has ever been regarded as a model; few, if any, approach him in brilliancy, finish, safety and effect; his mode of cutting the ball into the slips, on either side of the point, and above all his ‘forward play,’ is so peculiar that ‘None but himself can be his parallel.’ At ‘cover point,’ the spot usually occupied by him in the field, he is equalled by few, excelled by none.”

Later writers, looking back in reminiscence, added more to the discussion of Pilch’s excellent technique. Frederick Gale, who wrote The Game of Cricket in 1887, recalled Pilch giving him batting tips in 1845, when he recommended keeping the bat straight, discussed technique, stance and what guard to take on the stumps. He suggested waiting until being set in an innings before driving balls wide on the off-side, and noted that he preferred not to go hard at the ball. Instead, he played for gaps in the field (“it is safer, though less showy”). In 1899, William Caffyn (who played against Pilch in the 1840s and 1850s) stated in Seventy-One Not Out: “His attitude at the wicket was perfect, keeping both legs very straight … He played forward a great deal, and his bat went down the wicket like the pendulum of a clock … His best hit was one in front of cover-point. I do not think anyone ever excelled him in this stroke. He was a powerful driver when the ball came to him, but did not leave his ground much.”

But if he was famous for any particular shot, it was for his ability to reach forward to the ball and “smother” it; in other words for his forward defensive shot, something that no-one else had quite perfected before. Scores and Biographies in 1862 called Pilch “the best batsman that has ever yet appeared”, and explained that his batting was “commanding, extremely forward” and able to stop the best bowling before it could “shoot, rise or do mischief”. In other words, he got to the pitch of the ball better than anyone had managed. The 1896 edition of the Dictionary of National Biography said: “Pilch stood six feet in height, and possessed a great reach, which he further increased by designing a bat of the regulation length but with a very short handle, allowing a corresponding gain in the blade. His style of play was entirely forward, its feature being the smothering of the ball at the pitch before the twist or rise could take effect.” Pilch told Gale that this shot became known as “Pilch’s poke” and it proved extremely effective for Kent because his teammate Ned Wenman used to play back and cut. The necessity to pitch different lengths to the two batters caused the opposition bowlers problems. But Pilch also told Gale that some bowlers used to counter his methods: Alfred Mynn, for example, used to drop the ball short and fast, making it hard for Pilch to play forward.

By the 1880s Pilch was regarded as the father of the forward defensive shot. Whether or not this was true is less important than the fact that over forty years after Pilch retired, this was the popular perception. Gale, for example, said in 1887: “Fennex, be it remembered that he inaugurated the free forward play, and taught it to Fuller Pilch, and Fuller Pilch taught the world; for I feel confident, in my own mind, that all the fine forward play which one sees now sometimes, is simply , the reflex of what Fuller Pilch developed in a manner which has never been surpassed by any living man (except W. G. [Grace]), and that, too, in days when grounds were less true, and pads and gloves were unknown.” R. H. Lyttelton wrote in his book Cricket (1898): “There is strong evidence to support the conclusion that [Pilch] was the originator of what we understand as forward play.”

Like leading players of any generation, Pilch was worshipped by many admirers. Charlie Lawrence, an English-born influential figure in early Australian cricket, told the Australasian in 1898 how during his childhood, Pilch was his idol and he once “truanted” from school in order to see him in person playing at Lord’s (a twelve to fourteen mile walk). When he finally arrived, he heard that Thomas Box, Alfred Mynn, Nicholas Felix and William Lillywhite were also playing, “but the only attraction for me was Fuller Pilch.” He never forgot seeing him practise, and modelled his own style on Pilch, even though he was dismissed first ball in the match itself. In 1902 Arthur Haygarth, who played for Sussex before achieving greater fame as a cricket historian, recalled being presented fifty years earlier with a bat by Pilch for one performance at Lord’s; he said that “to have a bat offered by Fuller Pilch at headquarters was a high honour indeed in the cricketing world generally.”

William Lillywhite (Image: Wikipedia)

Therefore it is safe to say that until the 1890s, Pilch was taken as the exemplar of batting. He had a reputation for style and elegance, and his record of ten centuries (not all of which are today recognised as first-class) was seen as exceptional at the time. In 1899, William Caffyn stated: “There have been few, in my opinion, to surpass Pilch as a batsman with style and effect combined … He not only utilised his forward play for defensive purposes, but scored from it very frequently as well.” As the Dictionary of National Biography put it: “Throughout his career he was opposed to some of the greatest bowlers that have appeared, and ranked among the finest batsmen and run-getters. There was no player to contest his supremacy until George Parr reached his prime, about 1850.” One story that appeared quite frequently was that one of the greatest achievements of William Lillywhite, a famous bowler from Pilch’s time, was to bowl sixty balls to Pilch without conceding a run, and to dismiss him from the sixty-first. And the duels between Lillywhite and Pilch acquired legendary status in later years, being used to emphasise the greatness of both players. But there is just a hint of tension. Haygarth told a story in 1902 about one match at Lord’s when he played in a team with Lillywhite against opposition that included Pilch. When Pilch came into bat, someone shouted: “Hullo Lilly, here comes your master!” Irritated, Lillywhite spun round and replied: “I wish I had as many pounds as I have got out Pilch.”

Of course, as Pilch was a professional, it was just as important to his middle and upper-class audience that he was utterly respectable, and writing (especially in later years) emphasised this. Box wrote in 1848: “Pilch possesses in a remarkable degree the inestimable property of self control; no temptation will induce him to protract the festivities of the night by which the duties of the coming day would be in jeopardy; his temper is never ruffled by trifling breezes on the one hand, nor provoked by the tornado of unruly passion on the other … He is hailed with pleasure in all circles where the game of cricket is cultivated, and in his own he is the very idol.” A tribute to Pilch in the Licensed Victuallers Gazette during the 1880s recalled “his frank, open, pleasing face and civil manners.” The Dictionary of National Biography proclaimed: “Of a kindly disposition and quaint humour, Pilch was universally respected.” William Caffyn said: “He was exceedingly good tempered, and very kind to all young players with whom he came in contact. He was a remarkably quiet man, with no conversation, and seemed never happier than when behind a churchwarden pipe, all by himself.” In 1902, the former Kent cricketer W. S. Norton (who had played alongside Pilch) told Cricket that Pilch was “a very quiet old chap [who] delighted in a sly joke, over which he would look as sober as a judge.” If it all seems too good to be true, Pilch himself backed up the idea that he lived a respectable life. He told Gale that he limited himself to “two glasses of gin-and-water” in evenings before matches, even when he was being offered drinks by friends and acquaintances: he used to tell the landlords that if someone bought him a drink, to leave out the gin so that he was secretly only drinking water.

But there was another side to Pilch that seems surprisingly modern, even if it does not perhaps reflect quite as well on him. Like many retired players, he railed against the modern game and was firmly of the school that believed cricket wasn’t what it used to be. He told Gale that “modern” (i.e. during the 1860s, before his death in 1870) cricket was played far too frequently and had become predictable. He had little positive to say about how cricket had changed. Although he thought that fielding at long stop (a position that was increasingly obsolete) had improved, he believed that modern bowling and amateur cricket was inferior to his own day. He told Gale: “There is so much swagger and dress in the cricket field now sometimes, and so much writing and squabbling with committees and secretaries and players about cricket, that I often feel that the heart of the game is going, and that very many are playing for their own glory more than for their county now. I know this, that we played for the honour of the county and the love of the game first, and, of course, the gentlemen took care of us in the second place.” Given that in his playing days, Pilch had switched counties for money, this was slightly hypocritical. He also became annoyed if alternative views were expressed, particularly when people said that cricket in his day could not have been as good: “Well, according to your own showing, if nothing was so good thirty years ago, when you came into the world, you admit that your father and mother were not so good as the fathers and mothers now.” And he was less than keen on the increasing importance of counties, suggesting that the game had “drifted into committee cricket”. In short, it would not be difficult to imagine him, had he lived in the twentieth or twenty-first century, sitting in a broadcasting studio disparaging modern cricket like certain ex-players have done: perhaps the nineteenth-century version of Fred Trueman on Test Match Special?

Also, at a time when professionals continued to fight the amateur establishment for control of English cricket (a battle that would be ultimately lost), and more and more cricket was crowded into the calendar, Pilch looked back nostalgically to his own day. He believed that, in the time before railways made travel easier, cricket matches were more of an attraction owing to their rarity, and were something of a holiday event. He recalled how professionals such as him played at the houses of “noblemen”, or sitting with the butler drinking and smoking cigars, while gamekeepers, housekeepers and ladies’ maids came in briefly. Sometimes the “young gentlemen” “came down” to “talk cricket”. He viewed this as the ideal, a time when “gentlemen were gentlemen, and players much in the same position as a nobleman and his head keeper maybe”. Such an attitude would have been viewed unfavourably by professionals such as William Clarke, and even more so by the professionals playing in the years after Pilch’s death who might have read his views when Gale published them in 1887.

But by then, Pilch’s position as the supreme batter was no longer secure. If George Parr was regarded as something of Pilch’s equal, he never quite had the same reputation and it took something exceptional to dislodge Pilch. The first shake of the tree came in the rapids improvement in the standards of pitches at the end of the nineteenth century; far more runs were scored, batting aggregates ballooned so that scoring 1,000 runs in a season became a regular occurrence, and centuries became commonplace. Suddenly, at a time when W. G. Grace was able to score a hundred hundreds, Pilch’s feats seemed puny by comparison to those who subscribed to the view that cricket was far better than it once was. For example, an 1891 article in Cricket noted that “we may feel inclined to laugh at the feat of that truly great cricketer Fuller Pilch, in scoring ten centuries, and ten only, in the course of a life-time”, even if his feats still deserved respect.

W. G. Grace in 1872 (Image: Wikipedia)

But it was the emergence of W. G. Grace in the 1870s that finally eclipsed Pilch in the minds of most cricket followers. As he accumulated scores that would have been beyond the imagination of previous generations, Pilch provided the obvious point of comparison. Most people agreed that Grace was better or had taken batting to a new level. For example, the Kent captain Lord Harris wrote in 1883: “I know there are some, who have seen both players [Grace and Pilch], and are thoroughly competent judges of the game, who assert that if Fuller Pilch had had the advantage of playing on the same perfect wickets as Mr. Grace, he would have got as many runs; and, furthermore, they maintain that some of the bowlers Pilch had to contend against were more difficult to score off than the best of the present day. That the wickets were not as good in Fuller Pilch’s day is an undoubted fact, and their unevenness undoubtedly would tend to make balls shoot, rise, and break unexpectedly; but that the bowlers of those times were more accurate I cannot believe.” A few years later, Gale wrote: “I say of my friend W. G., that he has simply perfected the art which Pilch taught, though Pilch was never such an all-round man as our present champion, to whose wonderful cricket powers have been added the activity of a cat, and the constitution of a rhinoceros, and the light-heartedness of a schoolboy.”

And yet not everyone approved of the direction that cricket had taken. Cricket: A Weekly Record of the Game frequently featured interviews with old players, particularly around the turn of the century as the last survivors of Pilch’s generation were tracked down and their stories told. In 1902, Haygarth said in its pages that back in the days when Lillywhite and Pilch opposed each other, “the game was not all one-sided as it now is, for neither batting nor bowling had the upper hand. Equality prevailed always, and the science of the game was delightful to behold in consequence.” Interviewed in 1901, the former Kent player H. B. Biron said that while he was not sure what Pilch would have done in cricket of that time, “he certainly would not have left off balls alone; nor would he have paddled about with his legs when a leg-break bowler was on.”

And the historian and proto-statistician F. S. Ashley-Cooper, a regular contributor to Cricket, compiled a list of Pilch’s ten centuries in 1900. Feeling the need to defend Pilch’s record, he wrote: “To modern cricketers the above list of century-scores may seem but a small one for a man who for several years was the acknowledged champion batsman of England. But in Pilch’s day, and even more recently, run-getting was a vastly different matter to what it is to-day, and there can be no doubt that had Fuller Pilch had the opportunity of playing on billiard-table wickets he would have made scores which would have been considered large even in these days of huge scoring.” Ashley-Cooper wrote many times about the cricketers of Pilch’s time, and how they would doubtless have succeeded in conditions prevailing at the time. In fact he argued in 1900 (along with other leading cricketers) that batting had actually declined since the mid-1880s (Ashley-Cooper even resorted to the tired assertion that “the majority of those who have closely followed the game during the past few decades will probably agree”) and that “it is impossible for the present generation to realise to how great an extent the batsmen of years gone by were handicapped.” And interviewed in 1902, W. S. Norton judged that “if [Pilch] had been born later he would have rivalled W. G. himself. But cricket was quite a different game then, and it has now lost a good deal of the variety which made it so charming.”

Perhaps the most extreme reaction against modern cricket in defence of Pilch came from an anonymous correspondent to Cricket in 1896, who in response to an article on Grace wrote: “Pilch’s ten centuries were made on bad grounds, and without boundaries. Pilch played cricket, Grace plays boundary. Moreover Grace has played very many more played innings than Pilch. But comparison is impossible. There is not more difference between whist and bumblepuppy than between cricket and boundary. Put Grace on a bad ground to face [William] Clarke, [Alfred] Mynn, [John] Wisden and [Samuel] Redgate at their best, then you might talk about his wonderful comparative facts, but I don’t think you would.”

This obsession with the past, and the insistence that cricket was not what it used to be has continued to the present day, but just as it does today, the horizon shifted, leaving behind players from the more distant past. By the time of Grace’s death in 1916, there were few — if any — people alive who could remember seeing Pilch bat or discuss him with authority. And the emphasis had shifted once again. The editor of Wisden, Sydney Pardon, wrote a tribute to Grace for the 1916 almanack: “A story is told of a cricketer who had regarded Fuller Pilch as the last word in batting, being taken in his old age to see Mr Grace bat for the first time. He watched the great man for a quarter of an hour or so and then broke out into expressions of boundless delight. ‘Why,’ he said, ‘this man scores continually from balls that old Fuller would have been thankful to stop.’ The words conveyed everything. Mr Grace when he went out at the ball did so for the purpose of getting runs. Pilch and his imitators, on the other hand, constantly used forward play for defence alone.” This was not true, but by then it did not matter. Grace had replaced Pilch as the standard-bearer for “cricket is not as good as it used to be”, and he continued to be the point of comparison (and lightning rod) for all batters until the emergence of Bradman (and perhaps Hobbs).

We can never be sure how good Pilch was, or how the players of different eras would compare against each other. No-one mentions Pilch now when the names of great batters are discussed, not even those who love cricket history enough to recall Grace or Ranjitsinhji. But perhaps the way in which his reputation and legacy were continually revised — from disciple of Fennex, to the greatest in the world, to a sign that cricket was in decline, to proof that Grace was the ultimate batter — set the pattern that is still followed to this day of cricket followers seeking to either prove that their current hero is the best of all time or to argue that cricket simply isn’t as good as it used to be. Even so, perhaps whenever a forward defensive shot is played, it is worth remembering Pilch, the man who — possibly — first perfected it.