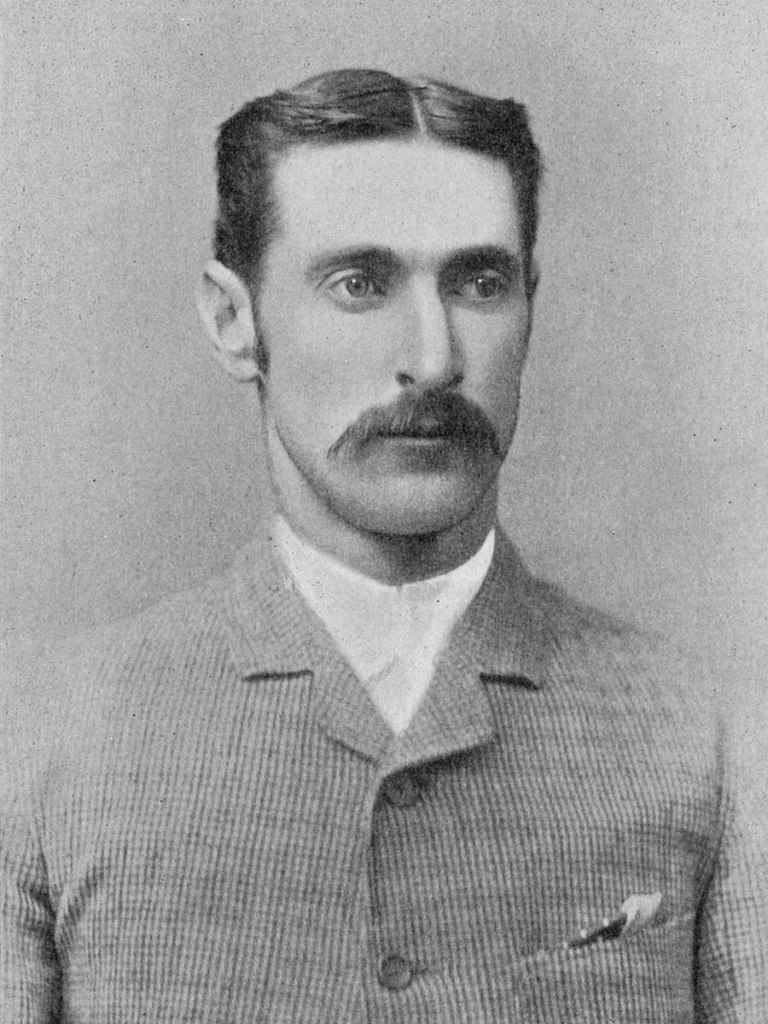

Jack Blackham (Image: National Library of Australia)

Cricket orthodoxy has often lurched between extremes as rules and tactical theory have changed over time. What seems obvious to a modern cricket audience would have been utterly ridiculous to one in the past, and vice versa. For example, bowlers used to rub the new ball on the ground to remove the shine; spinners always opened the bowling; gentlemen did not hit the ball to leg. Just occasionally, echoes of the past survive into the present. The expression “sticky wicket” is still used even though pitches have been covered for almost sixty years and few modern cricket followers can ever have seen one affected by rain. And while many people are familiar with the idea of a “long-stop” fielder, positioned directly behind the batter, that position is all but obsolete except in school games or the lower reaches of amateur cricket when the wicket-keeper proves unable to stop the ball effectively. For many years, this was one of the most essential fielding positions, yet it disappeared from first-class cricket remarkably quickly. How did the long-stop become extinct? The reason was the evolution of the role of the wicket-keeper, as a massive improvement in the skills of leading practitioners brought about the change.

Wicket-keeping is one of the few areas of the game which has changed massively over the years without any outside intervention. Although modern wicket-keeping gloves and pads are far more robust than their historical counterparts, these technological improvements have not altered the role of a wicket-keeper. In fact, there is a strong argument that wicket-keepers from the past were far more skilful than those of today simply because they did the same job with flimsy gloves while standing up to the stumps far more often — with the result that wicket-keepers were usually recognisable in retirement because of their gnarled and deformed hands. But despite their superior equipment, modern wicket-keepers in men’s cricket only stand up to spinners; until the 1960s, they did so to fast-medium bowlers. On the other hand, wicket-keepers are now expected to be able to bat in the top seven whereas in the past they were selected purely for their ability with the gloves; it was not unusual for a wicket-keeper to bat at number eleven and few wicket-keepers were particularly good with the bat. Expectations continue to increase in this regard so that wicket-keepers are primarily chosen for their batting ability; as a result, most commentators agree that in men’s cricket, wicket-keeping standards have declined as runs are prioritised over skills with the gloves. It is almost unarguable that the best wicket-keepers in the world today are to be found in women’s cricket, in which it is frequently necessary to stand up to the stumps. Comparing the batting and glove-work of leading practitioners from different eras would be a revealing exercise, although any analysis is hampered by the lack of any useful statistical judgement on how good a wicket-keeper is; instead, we only have the opinions of those who have seen them.

However, the biggest changes in wicket-keeping came in the 1870s and 1880s, when the entire role was practically reinvented by some highly skilled practitioners.

Before this time, the wicket-keeper was there solely to dismiss the batter through a catch or stumping; their role was not to stop the ball. Pitches were often uneven; it was quite possible for the ball to shoot unstoppably along the ground — this meant a wicket if the ball was straight but byes if it was not. Additionally, the main form of bowling, especially before overarm bowling was legalised in 1864, was round-arm. Faster bowlers operating with this method were often inaccurate, and wild deliveries which flew wide on either side of the wicket were a regular feature of the game. The wicket-keeper could not have been expected to take every ball, particularly as he almost always stood at the wicket for potential stumpings, even to the fastest bowlers. Therefore, the job of stopping the ball was allocated to the long-stop, a fielder standing directly behind the wicket-keeper whose job was to prevent byes.

“Old Stonewall”: William Mortlock in 1864 (Image: Illustrated Sporting News, 20 August 1864)

As the ball could shoot along the ground or fly wide, it was not easy being a long-stop, so the position was often filled by the best fielder on the team. Some bowlers were fast enough that they used two long-stops; Gerald Brodribb notes in his Next Man In (1995) that one bowler named Marcon used three long-stops. And when byes were listed on the scorecard, the name of the long-stop was often given too. In some publications, long-stop averages were published. For example, Bell’s Life in November 1860 revealed the best long-stop that year had been William Mortlock, who played for Surrey and was a regular for the Players against the Gentlemen. He had conceded only 15 byes in 17 matches and 30 innings (10,168 deliveries); three of those byes were recorded when there was no long-stop, and another four came from a deflection off the wicket-keeper, meaning that Mortlock really only conceded eight byes. His skill in the position resulted in his nickname: “Old Stonewall”. However, “long-stop averages” do not seem to have been commonly printed. The Kentish Mercury in 1861 noted as part of the Kent averages for the season that the long-stop William Goodhew had conceded 37 byes in seven matches, but the practice never seems to have been widespread.

While the idea of a long-stop remains in cricket consciousness, there is a modern misunderstanding of what the historical role involved. Today, we usually think of long-stop as a fielder right on the boundary behind the wicket-keeper. But the historical long-stop was not there simply to stop the wayward delivery crossing the boundary (in fact until the 1860s there often was no boundary). As William Clarke wrote in an 1851 article (reprinted in Cricket in 1884), long-stop was best positioned close enough to the wicket to stop a single being scored; Clarke even seems to suggest that some long-stops stood too close. It was also the case that long-stop often took catches — not something a fielder positioned on the boundary would have expected. For example, our superstar Mortlock held 44 catches in 81 matches between 1854 and 1862; in 1860, the year analysed in Bell’s Life, he had four catches in 12 first-class matches. For long-stop to be taking catches (assuming that batsmen in this period were not playing ramp shots, and that bowlers were not so fast that edges carried to the boundary) suggests that he quite likely was positioned almost where a modern wicket-keeper would stand to fast bowlers.

When R. H. Lyttleton, a top-class wicketkeeper who played between 1877 and 1887, wrote about long-stops in a chapter for his and A. G. Steel’s book Cricket in 1888, he said that the best long-stops “stand rather on the leg side, and if the bowling is very fast, just deep enough to take the ball as it rises after its second pitch. This is not easy to do, and young hands feel tempted to leave more room. But this, when the ball is very swift, scarcely diminishes its speed at all, and the further off long-stop stands, the more chance there is of the ball bounding awkwardly by the time it reaches him.”

Although long-stop has long been obsolete, the change came about only gradually, and it was common until the 1880s — especially when fast bowlers were operating — for a wicket-keeper to have a long-stop. Pinning down when each innovation arose is tricky and identifying the original wicket-keeper to make the change is all but impossible. Part of the issue may have been that spectators could see what was happening, but not all newspapers thought it worth mentioning, especially at a time when reports were dryly factual affairs concerning bowling changes and runs scored. All we can do in historical cases is look to see where something is unusual enough to warrant comment. We are also helped a little by the rather wearying tendency in old match reports to list every fielder and their position at the start of an innings.

The accepted version of history is usually that the Australian Jack Blackham was the man who first dispensed with long-stop during the first tour of England by an Australian team in 1878. But the picture is not quite so straightforward. There are several instances before Blackham in 1878. Brodribb lists some examples he had found. For example, A. H. Winter did not use a long-stop in the Oxford v Cambridge match at Lord’s in 1867, to widespread astonishment. But if there are plenty of examples before Blackham, they seem almost exclusively to have been when slower bowlers were operating. In fact, we can trace the practice of dispensing with long-stop for slow bowling quite precisely.

A match at Lord’s in the 1850s

In July 1844, a match took place at Lord’s between “Marylebone Club and Ground with Pilch” and “The Northern Counties with A. Mynn Esq.” Modern reference works refer to the game as MCC v North, but whatever we call the teams they contained some of the leading players of the time: Fuller Pilch, Frederick Lillywhite and William Hillyer for the MCC; William Clarke and Alfred Mynn for the North. The London Evening Standard for 16 July contained a report of the first day’s play which contained an almost throwaway reference: “There was a feature in this match which has upon no occasion been witnessed at Lord’s. Clarke bowled without a long-stop, and we think did not lose one bye.” The wicket-keeper was not named in any reports (and remains unidentified by CricketArchive on the scorecard for the game); there are several candidates as quite a few of the North team made stumpings in their career. But the unnamed wicket-keeper clearly did a good job. Clarke bowled underarm slow — and incidentally caused huge problems for the MCC batsmen, who according to the Standard were unaccustomed to facing such a style and therefore were very hesitant facing him.

It must quickly have become apparent that having an extra fielder available was a huge advantage to the bowling team which offset any extra byes conceded. The result was that the role of wicket-keeper gradually expanded to include gathering every ball without allowing it to pass. At first, long-stop was only removed when slow bowlers were operating, but this must have become common practice quite quickly. For example, the long-stop averages recorded in Bell’s Life in 1860 note that three of Mortlock’s byes were “obtained from slows when no long-stop”, as were four byes recorded against the second-placed Diver. Wicket-keepers seem to have gradually become more daring and long-stop became less important. One indication of the change in fashion can be found in the career of “Old Stonewall” Mortlock. From his 1851 debut in matches today designated as first-class until 1861, he never scored a half-century and his batting average was a touch over 13. From 1861 onwards, he scored three centuries and 22 fifties, while averaging 22 with the bat. He also began to bowl regularly; having bowled only 28 balls (for 19 runs and no wickets) between 1851 and 1860, he was a regular bowler between 1863 and 1867 and finished his career with 147 first-class wickets. This looks to be clear, albeit circumstantial, evidence that the greatest of long-stops had to find an alternative way to justify his place in the team from around 1862; was this when it became common for long-stops to be used less often?

But it was still notable enough to be mentioned in newspapers for there to be no long-stop for medium-paced bowlers. In 1870, Nottinghamshire’s Samuel Biddulph kept wicket to Alfred Shaw without a long-stop in a match against Yorkshire. In 1873, the Sheffield Independent noted in a report on a match between Sussex and Yorkshire: “As [the Sussex wicket-keeper Henry] Phillips keeps wickets without long stop, the score was opened with two byes off the first ball”. That this is stated as a fact rather than being unusual might suggest that Phillips had been doing so for some time. The opening bowler was James Lillywhite, a slow-medium left-armer. The lack of surprise in the reports might be an indication that some wicket-keepers by this stage commonly dispensed with long-stop to medium-paced bowlers, but for it to be noted at all means that it was still relatively unusual. And it should be emphasised that reports make clear — especially when describing the field — that long-stops were still regularly used.

Even if we cannot confidently date when fashions began to alter, by the late 1870s, many wicket-keepers only had a long-stop when the fastest bowlers were operating. The final step in the revolution was to dispense with the fielder altogether, no matter who the bowler was. Who was the first to take this final step?

In later years, the Yorkshire wicket-keeper George Pinder claimed in an interview with Alfred Pullin (“Old Ebor”) in 1898 that he had been the first man to keep wicket to fast bowling without a long-stop.

“The first man to do without a long-stop was myself, and I’ll tell you the match. It was a North v South game on the Lord’s Ground, Mr A. N. Hornby being captain of the North, and ‘W. G.’ of the South. Fred Morley was bowling at one end and W. Mycroft at the other. Mr. Hornby came up to and asked if I could do without a long-stop. I said, ‘Well, you know, sir, if one passes it means a four.’ He replied, ‘ Well, let’s try it,’ so of course we did. By and by, one ball which I could not get to went past me for four, so of course I looked at Mr. Hornby, who said, ‘Never mind that,’ and I went on without long-stop to the finish.”

The match being remembered by Pinder can only have been the North v South at Lord’s in 1877. Although Pinder’s claim to be the first ever to have no long-stop is patently false, if his memory was correct about the match, this would have been one of the first times a wicket-keeper dispensed with the fielder when taking a fast bowler. But no contemporary account seems to have thought this worth a mention. Does this mean that it did not happen? Or that it was not considered to be remarkable, and had perhaps happened before?

Others also made claims to have been the first: in Next Man In, Brodribb mentions Charles Brown of Nottinghamshire, Tom Plumb of Buckinghamshire, Richard Pilling of Lancashire and Mordecai Sherwin of Nottinghamshire. But while there are clear records of these men having no long-stop, most evidence comes 1878. Which brings us to Blackham, the man generally regarded as the pioneer of having no long-stop to fast bowlers.

Contemporary reports of the 1878 tour by the Australian team, when Blackham supposedly revolutionised wicket-keeping, take little notice of him. Early in the tour, some reports noted that Frank Allan was bowling with no long-stop, but this was because he was slow enough not to need one. The Daily Telegraph and Courier said in September, late in the tour, that “Blackham, as wicket-keeper, delighted the spectators by dispensing with long stop, and taking Spofforth’s lightning-paced balls with a single hand.” This was clearly unusual and perhaps unprecedented, but Blackham had definitely been using a long-stop earlier in the tour: the Birmingham Daily Post, giving a routine list of fielding positions at the start of the game between the Australians and “Twenty-two of the Birmingham Pickwick Club” in June, noted that there was a long-stop when Blackham was keeping to Allan and Spofforth.

In fact, Blackham does not stand out in contemporary reports during the 1878 season; an end-of-season report in the Nottinghamshire Guardian instead drew attention to the wicket-keeping of Frederick Wyld in Nottinghamshire’s match against the Australians in May, when it stated that his wicket-keeping “deserves especial mention, and was so safe that in the second innings, [the fast bowler Fred] Morley did not find it necessary to have a long-stop.” Blackham was on the opposing team, but the somewhat parochial report did not discuss him. There was also an instance of Surrey having no long-stop for the fast-medium bowling of Frederick Johnson recorded in The Times in June on account of the number of byes conceded by the county against Cambridge University.

The lack of reaction for much of the tour does not necessarily mean that Blackham was not doing remarkable things — as we have seen, newspapers are not always reliable indicators for innovation that creeps in gradually — but later accounts almost unanimously credit Blackham for being the first to dispense with long-stop to fast bowling. Even during his playing career — for example during features about him when he toured England in 1893 — he was recognised as the pioneer. Later accounts emphasise the wonder of what he achieved; these come a long time after the events they describe, making them less reliable, but might perhaps be better indicators than those sparse contemporary reports. One account written in an Australian newspaper in 1928 told a story of the surprise caused in England (which assuming that it was remembered accurately after fifty years, must have been when the Australians played Middlesex at Lord’s, the only match on the tour umpired by Bob Thoms:

“When the first Australian team played in England the famous umpire Bob Thoms looked with amazement when he saw Blackham standing up to Spofforth without a long-stop. He whispered to Tommy Horan who was fielding at square leg, ‘You’ve forgotten your long-stop,’ and he stared in amazement when Horan replied, ‘We never use one.’ As ball after ball was taken by Blackham, Bob Thoms could only murmur, ‘Wonderful, wonderful.’ From that moment no self-respecting wicket-keeper in England would belittle himself by having a long-stop.”

Blackham’s innovation had one crucial impact on cricket history, in one of the most famous and influential matches of all time. In the 1882 Test match — the “Ashes” match — between England and Australia, Blackham had no long-stop to Spofforth when Australia bowled England out in the fourth innings for 77 chasing 85 to win. This was at a time when most wicket-keepers still had one to faster bowling. Cricket noted the accuracy of Spofforth and the skill of Blackham to use this strategy when every run was at an absolute premium; and it is not impossible that having the extra fielder made all the difference to the result, which created the legend of the “Ashes”.

Blackham was modest about his achievements. In an 1893 interview, he suggested that other Australian wicket-keepers had dispensed with long-stop before him, although he suspected he was the first to do so to express bowling. He told how he realised he did not need one when keeping to a South Melbourne fast bowler called Conway, and he noticed that the long-stop never touched the ball; his captain therefore moved long-stop. Just 15 years after he had caused a sensation in England, he noted: “In first-class cricket now we should look upon a wicket-keeper as a bit of ‘a muff’ were he to ask for a long-stop.”

Whether Blackham was actually the first wicket-keeper to remove long-stop for fast bowlers is impossible to answer with certainty. Maybe Pinder did so before him; maybe even Wyld in 1878, or someone else unrecorded by history. It does not matter too much except that we can reliably date the practice to the late 1870s. We are on much firmer ground in suggesting that Blackham was the man who popularised the tactic for all wicket-keepers, and his performance in 1878 was the beginning of the end for the position of long-stop.

The idea of who was the first wicket-keeper to dispense with a long-stop became ridiculously controversial more than forty years later when Wisden — principally through its somewhat miserable and reactionary editor Sydney Pardon — took issue with the claim that Blackham was the pioneer. In a bizarrely jingoistic “Notes by the Editor” in the 1922 edition — possibly stung by the fact that Australia had just won eight consecutive Tests — Pardon wrote:

“I was frankly astonished to read one day last summer that Blackham taught Englishmen to keep wicket. To those of us who could recall Pinder, Pooley and Pilling in their prime this was too much. Pilling came out for Lancashire in 1877 — the year before Blackham was seen here — and potentially great in his first match. Blackham was by general consent the best of all wicket-keepers, but he did not discover a new art. The whole science of wicket-keeping does not consist in dispensing with the long stop and as a matter of fact Pinder was the first to do that in a North and South match at Prince’s [this probably refers to Pinder’s claim to “Old Ebor”, when the match in question was at Lord’s]. One can say without much risk of contradiction that Tom Lockyer during the tour of George Parr’s team in 1863-64 taught the Australians to keep wicket. It is quite possible that Blackham as a child saw him at Melbourne.”

Eleven years later, Blackham’s obituary in Wisden (now edited by Charles Stewart Caine) grudgingly conceded that he may have been the best wicket-keeper of his time, but still managed to disparage the claim that he was the first to dispense with long-stop:

“At different times it has been urged on behalf of Blackham that in standing up to fast bowling without a long-stop he set a new fashion — indeed that he first taught Englishmen what wicket-keeeping really could be. This claim is incorrect. Several English wicket-keepers — George Pinder, of Yorkshire, Tom Plumb, of Buckinghamshire and, most notably, Dick Pilling, of Lancashire — were always prepared to stand up to fast bowling without a long-stop, and often did so, but on the rough wickets of 60 years ago or more the ball flew about to such an extent that the practice of doing without long stop was, generally speaking, ill-advised.”

Curiously, when Blackham was named as one of the “Five Great Wicket-Keepers” in the 1891 Wisden, the citation (presumably written by Pardon, who had taken over the role of editor that year) was less equivocal about how good he was, and stated: “No one, to our thinking, has ever taken the ball quite so close to the wicket as Blackham, and, as is well known, he was one of the first wicket-keepers who regularly dispensed with a long stop to fast bowling.” What seemed to have irked Pardon in later years was the claim that Blackham was the sole pioneer. Certainly by the mid-1890s, he was the one given the most credit, but the story was more complicated than that.

After Blackham — or Pinder, or Wyld — began keeping with no long-stop to fast bowlers, it was not a signal for everyone immediately to follow suit. Even so, orthodoxy switched remarkably quickly so that by the middle of the 1880s, long-stop had practically vanished from first-class cricket.

George Pinder in 1875 (Image: Wikipedia)

It was still notable in 1879 that Pinder had no long-stop against a touring Canadian team; similarly, it drew comment that Ulyett bowled without one in Australia in 1881–82 and for Yorkshire in 1882, and that Joe Hunter of Yorkshire had no long-stop to the fast bowlers in 1883. Hunter was also singled out by Wisden for his work during the 1884–85 tour of Australia: “Hunter kept wicket admirably. He was in brilliant form at times, and always stood up to the fast bowling of Ulyett without a long-stop.” Around this same period, Richard Pilling of Lancashire also seems to have distinguished himself by having no long-stop to the fast bowler Jack Crossland; an obituary in the Lancaster Gazette in 1891 remembered how Pilling had stood up to Crossland and when someone was bowled, had “been seen to take the ball with one hand and the flying stump with the other with equal calmness”.

Soon, the practice had even spread to local and club cricket: in 1882, the Barnsley Independent reported that the local team’s wicket-keeper T. Bonson had dispensed with long-stop; the following year P. M. Walters of Leatherhead was singled out for having no long-stop in Cricket. But it did not always work. In a match played by the touring Australians in 1882, Billy Murdoch kept wicket in the absence of Blackham and had no long-stop to Spofforth against Middlesex; he made something of a mess of it, conceding 29 byes out of a first-innings total 104. That he conceded only one in the second innings might suggest he used a long-stop.

By the time he was writing for the Badminton book on cricket, Lyttleton said: “Wicket-keepers are so good, the bowling is so straight, that, in the present year (1888), it is impossible to say who is the best long-stop in England, for the simple reason that no long-stops are wanted. But in the days of yore, every schoolboy who was fond of cricket could tell you of the prowess of Mortlock, H. M. Marshall, and A. Diver. Mr. Powys was a splendid bowler, and so was Mr. R. Lang.”

Not everyone liked the change. A letter printed in Cricket in 1882 from T. Edwards of Blackheath lamented the “modern freak of doing without a long-stop” owing to the numbers of byes being conceded. He singled out a recent match between Surrey and Oxford University when the county had conceded 12 byes and 6 leg byes in a total of 78, and he implored the Surrey captain to field a long-stop. But soon long-stop was confined to club and school matches until the position was almost extinct. The use of a long-stop now became notable; the obituary of Frederick Fane in the 1960 Wisden recalled: “At Leyton in 1905, when Essex beat the Australians by 19 runs, Fane ended the match with a remarkable catch at a position approximating to deep long-stop where, with Buckenham bowling very fast, he had placed himself to save possible byes.”

However, it may not be a coincidence that the practice of wicket-keepers standing up to fast bowling became rarer as they edged backwards to save byes. Some thought that wicket-keeping had been changed for the worse by the alteration in its focus. Lyttleton thought that it spoiled wicket-keeping and affected his own form. And an anonymous “old Cambridge captain” wrote in the 1895 Wisden: “One reason why so few bowlers bowl round the wicket now is because they cannot do so safely without a long stop. I may be wrong, but my opinion is that the ball which beats the batsman inside the leg stump will very often beat the wicket-keeper too, especially if it shoots. Bowlers don’t like the balls to go for byes. Aiming at the leg stump, some balls must go crookedly and outside the legs of the batsman, and these the very best of wicket-keepers cannot always secure.”

Today, long-stop would almost certainly never be seen in a first-class match, except in highly unusual circumstances. One such example came in January 1998 when the England team touring the West Indies faced Jamaica in dangerous conditions; Jack Russell — one of the best wicket-keepers of the last fifty years — had to resort to using a long-stop (and wearing a helmet) while standing back to the quick bowlers, such was the impossible nature of the pitch. And sometimes a version of long-stop reappears in T20 cricket to prevent the ramp shot, or in junior and amateur cricket to protect an incompetent wicket-keeper. Although not the essential position it once was, long-stop is still remembered, an odd historical relic. And it survives in a surprising place: in the legal world a “longstop date” is an informal name for the latest date by which the conditions of a legal contract must be met. But on the cricket field, the days of the world-famous long-stop are long gone.

Thanks for exploring another interesting topic. On the 1882 Ashes test, it seems that neither side employed a long-stop, at least at first. The Times report lists the opening fields for Peate, Ulyett, Spofforth and Garrett and none featured a long stop. Lyttleton conceded seven byes altogether and Blackenham nine.

LikeLike

Very true, but I’ll leave in the comment about the 2nd innings because Cricket singled this out as a factor in the win, which feels important. I also notice that Sherwin was singled out in the same publication for something similar, so it looks like something for which the writers were keeping an eye out.

LikeLike