Fitz Hinds in 1902, while playing for the a combined West Indies team against R. A. Bennett’s XI in Barbados

The first tour of England by a West Indies cricket team took place in 1900. It was a very low key affair, particularly after the visitors suffered heavy defeats in the opening games, causing the press and public lose interest. But results turned around so that when the team returned home, the overwhelming consensus was that the tour had been a success, and that the team had improved consistently throughout. At a time when the cricket-playing territories in the Caribbean were part of the British Empire, and life in those colonies was dominated by the white minority, it is perhaps unsurprising that ten of the fifteen players who formed the West Indies team were white. Most achieved little and have left little trace in the annals of cricket. The other five were black. Lebrun Constantine (who became more famous as the father of Learie) and Charles Ollivierre had the best batting records of the summer; both went on to have long and distinguished careers. The leading bowlers were the black professionals Tommy Burton and Joseph Woods. The final black player achieved little during the tour and even to those who follow cricket history closely is little more than a name. But of all the players who took part on that tour, the long-forgotten Fitz Hinds perhaps had more impact than any other, albeit inadvertently. An incident involving him in 1899, before he was selected for the tour of England, dragged the controversial (and as far as cricket in the Caribbean was concerned, very topical) issues of professionalism and racial discrimination into the spotlight. The dispute is not well-known but has received considerable attention in the academic world. But for all his importance, Hinds himself is largely a mystery; and, as it happens, even the name by which he is known in the cricket world is incorrect.

Anyone who looks on CricketArchive or ESPNcricinfo, or even in the pages of Wisden (which records his feat of taking ten wickets in a first-class innings), will find a man listed as Delmont Cameron St Clair Hinds. This person certainly existed, but he was not the cricketer Fitz Hinds. Nor will anyone who tries to find out more about Hinds have much luck in the usual places. His first-class career was brief and does not even include his greatest achievement because the 1900 tour of England never received first-class status.

However, Fitz Hinds shot to unwanted fame before he had been chosen for the West Indies. The story was rediscovered nearly thirty years ago by Professor Brian Stoddart and has featured in most academic studies of Caribbean cricket in this period. For it to make sense, a little more background is needed. Cricket had been introduced into the Caribbean as a recreation for white people, but had been gradually adopted by black and other non-white communities. However, in first-class cricket played between the various British colonies — the Intercolonial Tournament — the white selectors refused to include black cricketers in any of the teams. The Trinidad establishment was the most eager to include black players — not least because the leading bowlers on the island were black and any team without their inclusion was immeasurably weaker — but Barbados in particular was resistant and made it clear that its team would refuse to take the field against any opposition that included black players.

This racial discrimination was dressed up in more polite fashion. The ostensible reason for the omission was a desire for West Indian cricket to remain amateur. Throughout the Caribbean, there were several professional cricketers, and all were black. Their roles usually involved bowling to members in the nets rather than playing for clubs. However, in Barbados (although not in Trindiad, where black professionals appeared for Trinidad in first-class matches played outside the Intercolonial Tournament) it was unthinkable for these professionals to appear in representative cricket. The distinctions even spread further down the cricketing ladder. The premier competition in Barbados, the Barbados Cricket Challenge Cup (BCCC), was an all-white affair until 1893 when Spartan Cricket Club was formed for those non-white players who were refused admission to other clubs. But the intended membership was the emerging black middle-class, certainly not professionals nor even the working classes. At the same time, Fenwick Cricket Club was formed for working class black players, but it was excluded from the BCCC; instead it played “friendly” games against the other clubs, which Fenwick usually won by the end of the 1890s.

It was into this world that Fitz Hinds emerged as a talented cricketer in the late 1890s. He was one of the black professionals engaged by Pickwick, one of the all-white clubs, to bowl at members in the nets. Away from the cricket field, he worked as a painter. For reasons that are unclear (but could for example be explained if he had completed an apprenticeship as a painter and began working full-time in that role), he decided to leave Pickwick and play cricket as an amateur. The fall-out was considerable and even impacted on the 1900 tour of England.

Hinds attempted to join Spartan as an ordinary member (i.e. as an amateur, not a professional). Like all such clubs, acceptance of the application depended on the existing members and several were dubious at having an ex-professional at the club, particularly a man working in such a menial occupation as a painter. After some intense lobbying by his supporters, he was finally granted membership in mid-1899, but the other clubs in the BCCC were horrified at the idea of facing a former professional on the field. Pickwick were particularly unhappy as Hinds had been their employee. Even some of the Spartan members refused to take part in practice sessions with Hinds. But the attitude of those who refused to play against Hinds affected the integrity of the competition; their clubs were forced to field weakened teams which proved no match for Spartan, which won the BCCC for the first time. Hinds did moderately well, averaging 15 with the bat and taking 22 wickets with the ball at an average of under 7. His best performance came against his former club Pickwick, when he scored 24 and then took eight for 31.

The ensuing controversy — known as the “Fitz Lily affair” (according to Stoddart, “Fitz Lily” was a pseudonym of Hinds) — reverberated for some time. Although never publicly admitted, it was Hinds’ race that presented the biggest problem for the white clubs. In the world of Caribbean cricket at this time, “professional” was a synonym for black; and a professional cricketer always meant a black working-class cricketer. But colour was not the only factor. As Stoddart puts it, Hinds faced “intense pressure which arose from the social layering of Barbadian cricket, itself produced by the island’s sugar culture which allocated all members of the community a rank in its elaborately defined production hierarchy. It is important to note that colour was not the sole, or even the important, issue in the Hinds case; it was social position, as his rough treatment inside Spartan indicated. Barbadian cricket ideology and its imperial model demanded a minimum status for admission to its organized ranks.”

However, not every white player was opposed to Hinds taking part in the BCCC. One notable supporter was Clifford Goodman of Wanderers Cricket Club. He backed Hinds at the time and later wrote of him: “By his good behaviour, pluck and hard work in every department of the game, [Hinds] won golden opinions from even the bitterest of his opponents.” But even the differing attitudes among Hinds’ opponents had a deeper explanation: the social background of the white players, as Clem Seecharan has stated in Muscular Learning (2006). There were two distinct white classes in Barbados: the rich and influential plantation owners had always kept their distance from the merchants and commercial traders who formed the next “rung” on the social ladder and were regarded as “newcomers”. This distinction was also visible in cricket: of the two main white teams, Wanderers was the club of the elite, the plantation owners, while Pickwick was comprised of the merchant class. Seecharan writes: “Although [Pickwick] were no less accomplished cricketers, they still harboured an inferiority complex rooted in the old hierarchy. It is significant that the socially preponderant, and therefore more confident, Wanderers seemed to have evinced no opposition to the selection of a so-called professional (Hinds) by Spartan, the club of the coloured and black upper middle class.”

In this period, these older distinctions had begun to fade as in Barbados’ uncertain economic climate; for example, the commercial class had begun to buy plantations that were in financial difficulties. But cricket was further behind. Seecharan writes: “But the differential social distinction lingered, in this parochial little world, fostering a resilient taint on the new money of the commercial elite.” Wider society was somewhat more progressive than the cricket clubs; for example, the Barbados Bulletin complained about Hinds’ non-selection for the Barbados team that played in the Intercolonial Tournament. The editor of the Barbados Globe also took issue with Pickwick’s “stubborn refusal” to play against “poor coloured men”. Cricket, however, simply tightened the restrictions. While the 1900 tour was ongoing, Fenwick were refused full admission to the BCCC; they were allowed to play the other teams as an “associate member” but could not win the cup and once again several white players refused to take the field against them.

But the problem for Barbados cricket was that Hinds was clearly among the best cricketers on the island. And when the time came to choose a team to tour England in 1900, the selectors — appointed from each of the main cricket-playing territories in the Caribbean — picked Hinds. Furthermore, because he was no longer professional, he was chosen as an amateur, nominally of the same status as the white members of the team. To some in Barbados cricket, this was simply unacceptable. Another Barbados cricketer who had been selected in the West Indies team was Hallam Cole, a Pickwick player. When Hinds was chosen, Cole wrote to the selection committee threatening to withdraw if Hinds were selected as an amateur. He had no apparent issue with other black players in the team (including the two Barbados-born professionals Woods and Burton, who had moved to Trinidad to further their cricket careers, and the two amateurs Constantine and Ollivierre), but Hinds was the non-white Barbados-based player.

It should be made clear that the other two white Barbadian team members did not share Cole’s views. And he faced criticism from the press. The Barbados Globe hinted that Cole’s stated reason for withdrawal — Hinds’ amateurism — was not the full story. In other words, it was Hinds’ race rather than status that was the issue. Yet Cole’s apparent racism merely reflected Barbados society at the time: the ruling white minority excluded all other races from politics (through the inability to vote) and placed considerable obstacles (such as high interest rates) in the way of the their hopes of achieving financial prosperity. And, as Seecharan has pointed out, Cole “represented the more reactionary strand in white Barbadian racial attitudes,” because he came from the insecure second rung of white society, which perhaps felt more threatened by a perceived incomer like Hinds: “H.A. Cole belonged to the [commercial elite rather than plantation group]: he attended Harrison College and played for Pickwick. Therefore, the inflexibility of his response to the selection of Fitz Hinds bore evidence of all the social insecurities of the rising bourgeoisie: wealthy, but still dogged by their lower status in the white hierarchy with its assumption of superiority of the old planting families.” In the end, Cole did not tour. Hinds did, and was recognised as an amateur in England (for example, being listed as “Mr F. Hinds” on scorecards).

The West Indies team that toured England in 1900. Back row: M. M. Kerr, W. H. Mignon, G. V. Livingstone, P. I. Cox, W. C. Nock (manager); W. T. Burton, S. W. Sproston, C. A. Ollivierre. Middle row: W. Bowring, G. C. Learmond, R. S. A. Warner (captain), P. A. Goodman, L. S. Constantine. On ground: F. Hinds, J. Woods (Image: West Indies cricket history and cricket tours to England, 1900, 1906, 1923 (1923) by L. S. Smith)

Given all that led up to his selection though, it is perhaps unsurprising that Hinds struggled in England. Perhaps his presence on the tour was its own victory, but he would not have been helped by the conditions which were so alien to him and his team-mates. It took time to adjust to such matters as the slow pace of the outfield, the flat batting wickets, the different quality of light and the English weather. He managed to score two fifties, but only averaged 20 with the bat. He bowled little, only managing six wickets. Nevertheless, he did well as an occasional wicket-keeper (sharing the role with Constantine), for example taking five catches behind the wicket off the bowling of Burton against Norfolk. Perhaps his performances were a little disappointing, but writing in the 1901 Wisden, Pelham Warner judged that Hinds was “often useful in his peculiar style, and was a keen hard working cricketer.” S. W. Sproston, who took charge of many of the matches in the absence of the official captain, recalled in an interview printed in Cricket that August how, against Gloucestershire during an onslaught by Gilbert Jessop, Hinds “would not have a man out in the country [i.e. in the deep]. [Charlie] Townsend hit a ball which went past him towards the boundary, and two or three of the team were proceeding to go after it. But Hinds waved them back, calling out, ‘Leff all to me, I’m going for it’, and he went after it at a tremendous pace, leaving everybody else far behind.”

If Hinds had not set England alight, he remained a prominent cricketer afterwards. He continued to play for Spartan (and Cole and other white players continued to refuse to face him on the field) and became something of a popular hero. For example, when he was dismissed lbw for 43 against Pickwick in September 1900, the crowd noisily complained about the decision of the white umpire. A contemporary newspaper noted the danger of giving out a “favourite with the crowd”.

In January 1901, in the absence of any intercolonial competition that season, the white Barbadian A. B. St Hill took a team to Trinidad. The majority of St Hill’s team was from Barbados and included not only Hinds but several other black players (including two Barbadian professionals). The matches were judged to be first-class and therefore Hinds made his first-class debut when he played for A. B. St Hill’s XI against Trinidad in Port of Spain (ironically in a match that was played 12-a-side). He made an immediate impression, opening the bowling and taking ten for 36 in 19.1 overs (although this was a 12-a-side game, it is still recognised as first-class and usually included in lists of “ten wickets in an innings” even though eleven wickets fell in the innings). He took two wickets in the second innings but made less of an impression with the bat. In the second game between the teams, he bowled just two overs and again failed with the bat.

That September, Hinds played for Barbados for the first time, in the final of the Intercolonial Tournament (Barbados qualified automatically as the holders of the title) when he and Stephen Rudder became the first black players to represent Barbados. Presumably the realisation that if Hinds could represent the West Indies, he was good enough to play for Barbados (a point made by several English commentators in discussing the race-based selections of Barbados) led to his belated inclusion. And in the ultimate irony, one of their team-mates was none other than Hallam Cole, who must have overcome his objections by then. Hinds opened the batting in the first innings but achieved little with bat or ball. One letter to the Barbados Advocate before the tournament had suggested that Hinds was a “first-rate” wicket-keeper who should be played in that role, with someone else stepping in when he was bowling, but nothing came of this.

In January 1902, Hinds played for Barbados and a representative West Indies team (a “Combined Colonies” team that featured players from Barbados, Trinidad and British Guiana) against a touring English side led by R. A. Bennett. Presumably owing to injury, he did not bowl in any of the games. But opening the batting for Barbados in the first game, he scored 55 runs out of an opening partnership of 70, his first fifty at first-class level. During this innings he made quite an impression on the delighted crowd and bemused English team. Facing the slow leg-breaks of Ted Dillon, he switched hands after the ball had been delivered and tried to bat left-handed (in other words, what a modern spectator would call an attempted switch-hit) but seeing that it would not work, he turned his back to the bowler and hit the ball past the wicket-keeper. The Barbados Advocate recorded: “It was a novel stroke, and Bennett, who was behind the sticks, seemed rather uneasy when the ball was slashed past within a few inches of him. It was a stroke which required extreme agility and exactness, and we do not suppose any of our team beside Hinds would attempt it. It is unnecessary to say that the crowd cheered every such effort enthusiastically, and even the Englishmen were amused at the method of dealing with their attack.”

Despite this success, Hinds scored only 74 runs in four first-class innings across the three games (he also scored ten in a non-first-class game). After opening for Barbados, he batted down the order for the “Combined” team, which defeated Bennett’s team by an innings. When Barbados next played in the Intercolonial Tournament, in January 1904, Hinds retained his place and took a few wickets, but his only innings of note was an unbeaten 42 in the final (easily won by Trinidad). Yet he remained a certainty for Barbados and among the leading cricketers in the region. When Lord Brackley’s XI toured the West Indies in early 1905, Hinds played for both Barbados and in two representative matches for the West Indies. He played a few useful innings without reaching fifty, but took five for 41 in the second match between Brackley’s team and Barbados.

Those were Hinds’ final first-class appearances. In 12 matches, he scored 366 runs at 20.33 and took 29 wickets at 15.00. Yet if his record looks underwhelming, he was clearly respected enough to be a fixture in the Barbados team, playing every first-class match for the island between the tour of 1900 and the end of the 1904–05 season, and to be included in representative West Indies teams. And even more importantly, he was not just a beneficiary of parochial selection: he did not just play for West Indies teams chosen in Barbados, but was included by Trinidadian selectors when Brackley’s team toured in 1905. Therefore it was no reflection on his ability or his record that those matches marked the end of Hinds’ career in Barbados. He stopped playing because later in 1905, he emigrated to the United States.

Hinds continued to play cricket in the United States, although we have a record of only one game. In 1913, a privately organised (i.e. unofficial) Australian team toured North America. Many leading Australians, including the Test players Warren Bardsley and Charlie Macartney (and the former English Test player Jack Crawford) and the future Australian players Arthur Mailey and Herbie Collins, took part in the tour. One of the matches was played in Brooklyn, New York, a two-day game against the incongruously named “West Indian Coloured XI”, which had originally been called the “Cosmopolitan League” team. The game took place at Celtic Park, a ground run by the Irish-American Athletic Club, in Long Island, New York (it is wrongly listed as being in Brooklyn on CricketArchive, a mistake first made in Cricket in 1913). Hinds scored only one run in his only innings and did not bowl, injuring his foot in the field. He was replaced in the team by A. Marshall, and the Australians won by an innings.

If that was not quite the end of Hinds’ story, the final parts have remained a mystery until now because of a case of mistaken identity which caused his trail to go cold. The “Fitz Lily affair” was rediscovered by Brian Stoddart in the 1980s, and appeared in print in 1988, fully cited to contemporary newspapers and other publications (which was quite an achievement in the days before internet searches and digitised archives). Ten years later, the article was cited by Keith Sandiford in his Cricket Nurseries of Colonial Barbados (1998) but with one important difference. Sandiford identified Fitz Hinds as Delmont Cameron St Clair Hinds. This was subsequently accepted by all statistical authorities; Hinds is currently listed under that name by CricketArchive and ESPNcricinfo, and around this time, Wisden altered its record section so that credit for the ten for 36 against Trinidad in 1900–01 switched from “F. Hinds” (against whose name it had previously been listed) to “D. C. S. Hinds”.

Sandiford offered no evidence for this identification, nor have any of the people who have followed him in claiming that Fitz was really Delmont. There certainly was a man called Delmont Cameron St Clair Hinds; Barbados records show that he was born on 1 June 1880 and baptised in St Leonard’s Chapel in St Michael, Barbados, on 1 August 1880, the son of John Thomas Hinds (a coachman) and Jonna Hinds née Harewood, who lived on Westbury Road. However, there is no evidence to connect Delmont Hinds to Fitz Hinds. Quite how Sandiford (or whoever made the original link) settled on him as the most likely candidate is unclear. The identification, made at a time when records were hard to track down without a physical search, seems to have been somewhat haphazard. For example, there were other baptisms in Barbados around this time that could have been the cricketer, such as someone called Fitzhubert Alonzo Hinds, born in 1877 or Prince Arthur Alonzo Fitzgerald Hinds, born in 1899.

There are other issues around the claim that our cricketer was actually D. C. S. Hinds. For example, it is hard to see how the name Delmont Cameron St Clair could lead to a nickname of Fitz. Furthermore, all contemporary scorecards (rather than ones later transcribed onto computer databases like CricketArchive) list him as F. Hinds. While it could be argued that Caribbean newspapers might condescendingly use a nickname for a black cricketer, this does not quite hold true because Joseph Woods was known by the nickname of Float Woods but is listed on scorecards for the 1900 tour as “J. Woods”. A further problem with Hinds really being Delmont Cameron St Clair is that he was named on the list of incoming passengers to Southampton, alongside the other members of the cricket team, as “F. Hinds”, albeit with an erroneous age of 44. There are other reasons to doubt the identification. D. C. S. Hinds would have been 20 at the time of the 1900 tour, and only 19 when he joined Spartan. Given that he had been a net bowler before this, and had time to learn a trade as a painter, it seems unlikely that the actual Fitz Hinds could have been so young. A further problem is that D. C. S. Hinds has left no traces in any other records that can be traced online; this would be unsurprising if he had lived out his life in Barbados, but we know that Fitz Hinds emigrated to the United States, which kept copious records, almost all of which are readily available online. And in these, there is no record of a man called Delmont Cameron St Clair Hinds.

And it is these American records — unavailable to those first researchers in the 1980s and 1990s trying to find our man — that offer an alternative identity for Fitz Hinds. On 24 July 1905, a man called Fitzgerald Alexander Hinds arrived in New York from Barbados, on the S. S. Hubert. He was listed a 27-year old single man who gave his occupation as a painter. He had only $30 with him and was visiting a man called George McDermon, a Jamaican living in New York. This same man subsequently appears in multiple records, from census returns to certificates of naturalisation. While on other occasions he is listed as a porter, several records state that he was a painter. Could this be Fitz Hinds the cricketer? There are several elements that support such an idea: his birthplace of Barbados and his residence in New York (both of which we know applied to the cricketer; his address in 1913 — West 138th Street — was around nine miles from Celtic Park where we know Hinds played that year); his occupation; and the fact that “Fitzgerald” is a name far more likely to be rendered as “Fitz” than “Delmont Cameron St Clair”. It could also be argued that his age — a few years older than Delmont — makes it more likely that he could have achieved all that was recorded of the cricketer by 1900.

Fitzgerald Alexander seems a far more likely candidate for Fitz Hinds. Searches of the American records (which it should again be emphasised were impossible for earlier researchers) offer up no other realistic possibilities living in New York at the time. Incidentally, there is no obvious record of Fitzgerald’s baptism in Barbados, making it unlikely that he could have been found by anyone looking there in the 1980s or 1990s. And perhaps the clinching piece of corroboration that makes it likely that we have found the real Fitz Hinds is that the great-grandson of Fitzgerald Alexander Hinds was told by his father that the former had been a “world champion cricketer”.

Hinds’s signature from 1918

If we can be moderately confident that we have found the cricketer, the copious records taken in the United States allow us to fill in a lot of gaps about his life and learn what became of him once he emigrated. Fitzgerald Alexander Hinds was born on 17 September 1877 in Bridgetown, Barbados. He was the son of James Hinds (according to his death certificate) or Francis Hinds (according to his marriage certificate) Hinds and Annie Elkcott. The 1940 census reveals that he was educated until 8th grade (i.e. the age of 13 or 14); presumably it was after this that he began to learn his trade as a painter.

When Hinds arrived in the United States, he was already a father and might have had some complicated relationships. His first child, a son called Darcy, was born in 1902 but the identity of his mother is uncertain. Then in 1904, he had a daughter called Winifred with a woman called Maude Corbin (who might have been known as Maude Walcott). Hinds arrived in New York alone, but Maude soon followed (possibly a month later but definitely by 1906). In March 1907, they married in New York City; their second daughter was born the following month and in September 1907 their daughter Winifred (and Maude’s mother) came from Barbados to live with them. In total, the couple had ten children, from Winifred in 1904 to Maude in 1920.

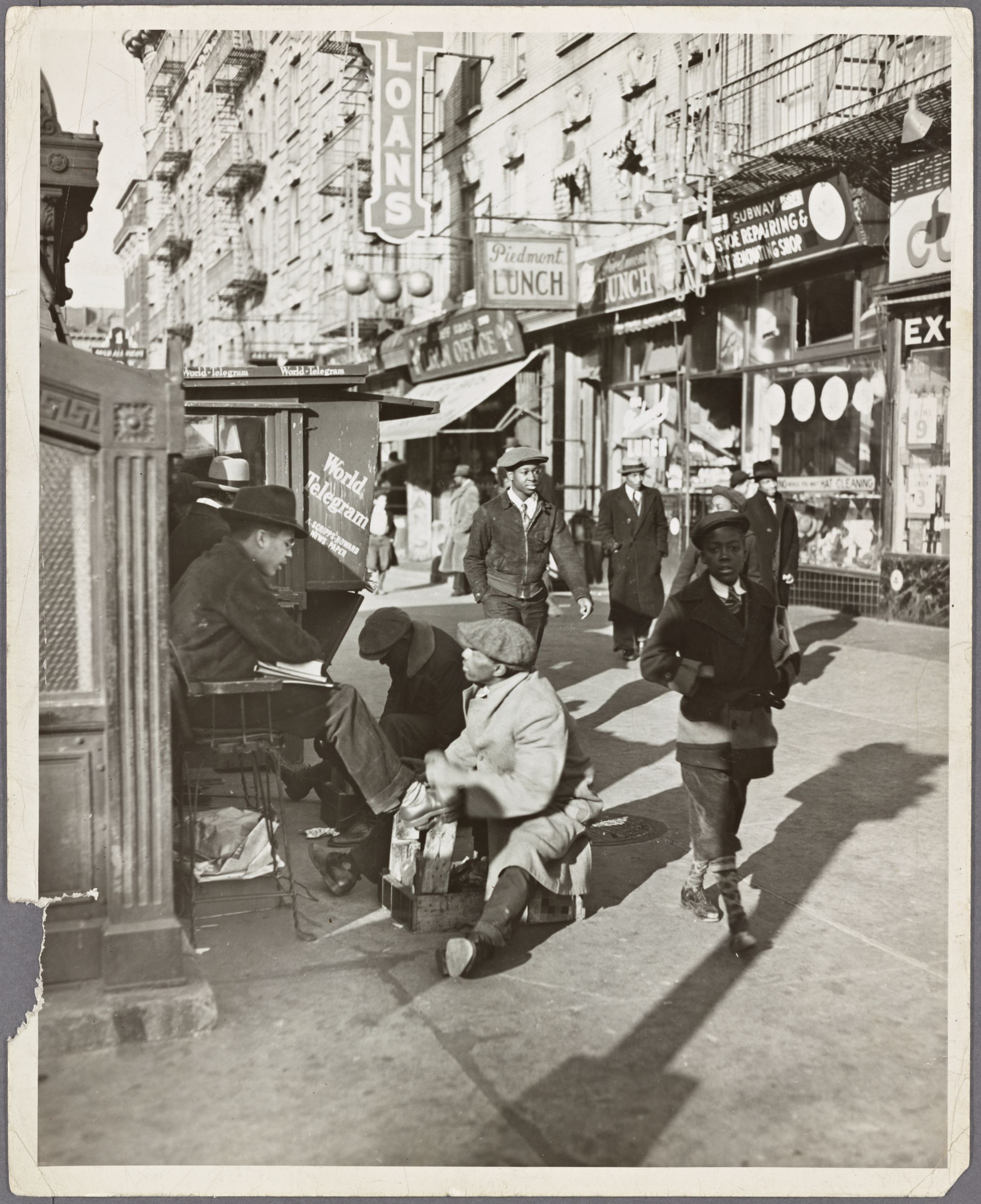

A photograph of Harlem (showing Lenox Avenue from 135th Street) in 1939, very close to where Hinds and his family lived from their arrival in the United States until around 1935 (Image: From The New York Public Library)

Through the United States Census (as well as the New York Census) we can trace what happened to Hinds. The family lived in Harlem, Manhattan, for at least thirty years after their arrival in the United States. The area in which he lived gave birth after the First World War to what became known as the “Harlem Renaissance” — the intellectual and cultural explosion of art, writing and music from African Americans based in Harlem. The Hinds family lived close to the areas that became the centre of the movement. They clearly had no desire to return to Barbados because in 1925 Hinds and his wife became naturalised citizens of the United States.

However, Hinds’ occupation was prosaic. In 1910, he worked as a porter in a department store, but by 1915 he was working as an elevator operator. After this, he seems to have resumed his main trade as a painter, which was his recorded occupation (specifically a house painter) in 1920 and 1925. Perhaps this suggests a period of prosperity, where he could take on less menial jobs. But it did not last. Perhaps the Great Depression played a part, but by 1930 Hinds was again working as a porter, initially for a gas company. By 1940 he was based in an office building, earning a salary of $1,350. Sometime after 1935, the family relocated to the Bronx. It is hard to gauge what life was like for them. They always rented their accommodation and often took in lodgers. But the family stayed close: even in 1940, when all the children were adults, many of them (even the ones who were married) lived at home, as did several of the Hinds grandchildren and Maude’s mother.

Maude died at the family home in 1941 at the age of 53; the cause of death was “Broncho Pneumonia, Diabetes Millitus and Bronchial Asthma”. Fitz died on 30 December 1948 at Lincoln Hospital. He was still working as a porter at the age of 72; no cause of death is recorded on the transcribed online indexes.

The grave of Hinds and his wife, located in Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York (Image: Kenny Hughes (a.k.a. Kenneth G. Hughes) via Find a Grave)

In the 75 years since Hinds’ death, no-one outside the family realised that he was once a famous cricketer. Even though the “Fitz Lily affair” was rediscovered and retold, becoming a topic of some importance in the academic study of cricket in the Caribbean, no-one was quite sure what had happened to the man at the centre, the man who had inadvertently affected the first tour of England by a West Indies team and forced the cricket establishment in Barbados to take a long look at its attitudes towards race and class. While his cricketing skill is almost secondary to the story, it should not be forgotten that — even if not entirely reflected in statistics — Hinds was one of the leading cricketers in the West Indies at the beginning of the twentieth century; he was so good that Barbados abandoned its “white only” policy in the Intercolonial Tournament. He even, if we consider that one fleeting reference to an attempted switch-hit and Warner’s comment about “his peculiar style”, played in a way that might not be out of place today, happy to improvise and break convention on the field as well as off.

In short, such a cricketer should be remembered rather more than he is. And at the very least, we should make sure that we have identified the right man in order to give him due recognition.