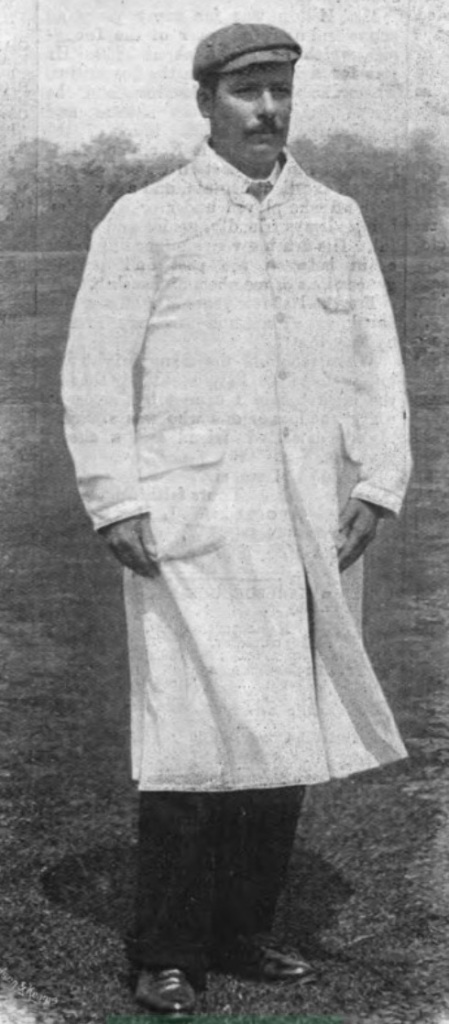

Valentine Titchmarsh (Image: Cricket, 31 May 1906)

Other than the occasional “celebrity” — such as Dickie Bird and David Shepherd, or, further in the past, Frank Chester and Jim Phillips — few umpires make an impression in cricket’s history books. But the various circumstances which led men into umpiring can often be fascinating. And if cricket writers have always ignored the men in white, who have largely performed their roles discreetly and anonymously over the years, that does not mean that they do not have their own tales to tell. For example Jim Phillips, the infamous crusader against throwing, had an extraordinary life. But some of his contemporaries had equally remarkable backgrounds.

At this time, umpires occupied a strange position in cricket. In a sport that was dominated by amateurs, who ruled every aspect of it, the umpire was always a professional cricketer. Some were retired players; others were members of the MCC groundstaff who combined umpiring with their playing duties and ground maintenance at Lord’s. But all were paid cricketers who were, remarkably given social conventions of the time, passing judgement on amateurs. However, their authority was not limitless as they owed their position to the county captains, who met annually to appoint umpires to the first-class list: keeping the captain happy was a job requirement for any umpire in this period. The list of umpires appointed for the 1900 season includes several interesting men, apart from Jim Phillips.

Four former Test players who were first-class umpires in the 1900 season

There were two participants from the first ever Test match, played in Australia in 1877: James Lillywhite, England’s captain in that game, and Alfred Shaw, who bowled the first ball. There were other international players on the list. Perhaps most famous was Richard Barlow, the Lancashire and England opening batsman who was one half of the inspiration for the famous poem “At Lord’s” which includes the line “O my Hornby and my Barlow long ago!” Another Test player was the remarkable Mordecai Sherwin, who played a total of 328 first-class games in a twenty-year career, mainly as Nottinghamshire’s wicketkeeper, but he also played in three Tests for England; he combined this role with a football career as Notts County’s goalkeeper between 1883 and 1888. Some other umpires had substantial first-class careers behind them, such as John Wheeler and Walter Wright who played for Nottinghamshire in the 1870s and 1880s, or William Hearn who had a long career on the MCC groundstaff. And there was one veteran on the list: the 74-year-old Bob Thoms, who played three first-class matches in the 1850s and had been umpiring since the 1860s.

Even from this brief glance, the number of former Nottinghamshire players is remarkable; in fact, 24 players who appeared for the county between 1835 and 1914 went into umpiring when their playing career ended, which is unsurprising as there were few opportunities at the time for former professional cricketers. But for now, it is worth looking at someone not linked with Nottinghamshire. Valentine Titchmarsh was a highly regarded umpire associated, like Phillips, with the “Throwing Question” in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Like Phillips, when he was appointed as an umpire he was a professional on the MCC groundstaff. Despite great success playing for Hertfordshire, Titchmarsh’s first-class career was unremarkable. His death, on the other hand, is mysterious and, potentially, somewhat scandalous.

Valentine Adolphus Titchmarsh was born on 14 February 1853 at Belvedere House, Royston in Cambridgeshire — his birthday providing his first name. His father John was a miller and corn merchant. The family were evidently successful; although having six children to support, of whom Valentine was the second, they were able to employ servants and to send Valentine away to school. The 1861 census records him as a boarder at Lord Weymouth’s Grammar School in Warminster, when he was the youngest of 21 pupils.

The site of Weymouth Grammar School (Image: Wikipedia)

After leaving school, Titchmarsh helped his father to run the family business, but his real interest lay in cricket, which many of his family played. He quickly established himself as a promising batsman and in 1876 he was given a trial for the Hertfordshire county team. By the following season, he was a regular in the side, playing as an amateur. He was part of the team that played at Lord’s when his county faced the MCC. Later in that 1877 season, he took all ten wickets in an innings against Essex. A few weeks later, figures of seven for 30 in one game and six for 15 in another set the seal on an impressive first full season.

From 1879, Titchmarsh changed direction. He became a professional on the groundstaff of Oxford University, and remained there for five years. He continued to play for Hertfordshire, but now as a professional (with “Mr” dropped from his name on contemporary scorecards). Not many cricketers in this period started as amateurs and became professionals as this was a considerable step down in a social sense. We do not know why Titchmarsh made the change, but it is not unreasonable to guess that finance was the main reason.

During this time, Titchmarsh made steady progress. He continued to be successful with the ball, for example taking nine for 34 against Essex. While he never scored a century for his county, he made several substantial scores, including an innings of 97 against the MCC in 1893. In 1880, he made several appearances for the United South Of England XI, an all-professional team which played matches around the country. Among his team-mates were the manager Fred Grace, brother of WG, and Walter Gilbert, Grace’s cousin who had an interesting relationship with amateur status. In one of these games in 1880, North v United South of England XI, he made his first-class debut; this was his only such game before 1885. Titchmarsh also played regularly for St Alban’s Cricket Club; in October 1880, he scored 137 not out against XVIII of the Star Cricket Club.

Therefore, if Titchmarsh was never a leading cricketer, he carved out a decent career for himself and had a good reputation, especially in Hertfordshire. Perhaps had he lived in a county with a first-class team, he would have been very successful.

At the time of the 1881 census, Titchmarsh was boarding at the Crystal Palace Inn in St Albans, the home of James and Caroline Gentle, and listed himself as a professional cricketer. Meanwhile, his father appears to have retired and left the family business to one of his sons; John Titchmarsh died in 1885 although his wife lived until 1898. Soon after his father’s death, Titchmarsh married Eliza Maria Pew at St Albans in 1886. The couple had two daughters, Annie Maud in August 1887 and Lilian Ellen in December 1888.

In 1884, Titchmarsh joined the professional groundstaff at Lord’s, which was a natural magnet for many professionals unable to establish themselves in regular first-class cricket. His obituary in the Herts Advertiser said that he joined after impressing while playing for the MCC against Nottinghamshire — a match not recorded on CricketArchive — but he did face the MCC twice in 1883 while playing for Hertfordshire. The same article also suggests that he only joined the MCC after breaking several fingers in a match for St Albans in late 1883 — perhaps the injury affected his batting and taking a role with the MCC was a way to secure a regular income.

Titchmarsh’s first game for the his new club, a non-first-class match, was in August 1884. The following May he made his first-class debut for the MCC, taking five for 69 and eight wickets in the match against Cambridge University. He played two other first-class games for the club that season, and appeared in a match at Lord’s for the “South” against the “North” alongside WG Grace. None of these subsequent first-class appearances were particularly successful, but he also played in numerous other MCC matches throughout the season. In the higher-status games, he generally batted low in the order.

Valentine Titchmarsh in 1899 (Image: Wikipedia)

After 1885, he played just three more first-class games, all for the MCC: two in 1886 against each University team, and once in 1891 against Somerset. He played in other games for the club, albeit with decreasing regularity, until 1898; CricketArchive lists a total of 36 matches for the MCC, but he also appeared in games not on that database, including one in which he again took all ten wickets in an innings — this time against Sherborne School; the next day, he scored 101 not out against Rossall School. After his final appearances as a player, Titchmarsh remained a member of the MCC Groundstaff until his death in 1907. For Hertfordshire, he was a regular member of the team until 1897: CricketArchive records that he played 145 matches for the county, scoring 3,845 runs at an average of 16.71 and taking 648 wickets at 15.78.

According to Titchmarsh’s Wisden obituary: “Score and Biographies (xiv., 82) described him as ‘An excellent batsman, and a successful fast round-armed bowler, while in the field he takes no particular place … He is a left-handed batsman, but bowls and fields right.'” A feature in Cricket in May 1906 described him as a fast-scoring left-hand batsman, and a right-handed bowler who “sent the ball along at a good pace while able to take full advantage of a wicket which gave any help.”

But it was as an umpire that Titchmarsh became famous. Like his contemporary Jim Phillips, he first umpired through his role as a professional on a club’s groundstaff. As part of his duties with Oxford University, he officiated the freshman’s trial match in early 1882. Two weeks later, he took charge of his first first-class game when Oxford University took on the touring Australian team. He evidently impressed the Australians: he umpired two of their next three matches. The following season, he once more officiated at an Oxford trial game and then two of the university’s first-class matches; similarly, he umpired three first-class matches in 1884, his last season on the Oxford University groundstaff.

When Titchmarsh moved to the MCC groundstaff, he was not used as an umpire until 1887, when he took charge of two first-class games. From 1890, he umpired one or two matches each season until 1893, but unlike Phillips, who took charge of the most important matches at Lord’s, Titchmarsh was only used in lesser fixtures. Something changed in 1894 when he umpired five games at Lord’s, including the Gentlemen v Players match. After umpiring just once in 1895, Titchmarsh was appointed to the list of umpires for the County Championship in 1896 — perhaps making the switch as his playing career began to wind down. From then, he was a regular County Championship umpire until 1906.

The England team which played Australia in the first Test of the 1899 Ashes series. This was Titchmarsh’s first Test as umpire; he is standing on the extreme right. (Image: Wikipedia)

His reputation as an umpire was evidently a good one: he stood in one Test match in each of the Australian tours of 1899, 1902 and 1905; he also umpired the Lord’s Gentlemen v Players match from 1902 to 1904. Very occasionally, he made the headlines. He no-balled FJ Hopkins of Warwickshire for throwing in 1898, one of the first actions by an umpire in the “Throwing Question”. Then in 1903, he appeared in newspapers reports for checking the width of several bats in the opening match of the season — which was interrupted by snow at one stage — between Surrey and WG Grace’s short-lived London County team. This was the result of an instruction from the MCC that umpires should check that bats were the legal size. On the first day, two London County players were found to have bats that were too wide; one needed to resort to a third bat before he passed the test. It did not escape notice, however, that Titchmarsh waited until professional batsmen were at the crease, rather than amateurs, before taking out his gauge to measure the bats (in contrast, the umpires inspected the bats of all the players on the following day). A few weeks later, a Worcestershire batsman had to change his bat after Titchmarsh inspected it in a game against Sussex.

On other occasions, he was sent to check the legitimacy of disputed bowling actions, including that of Arthur Mold in 1901. But Titchmarsh was not a controversial or publicity-seeking umpire. Unlike some of his colleagues, he never sought the headlines, nor made any public pronouncements on controversial issues such as throwing. His obituary in Cricket stated that his reputation as an umpire “stood deservedly high” and Wisden called him “one of the best umpires of recent years”. The 1906 feature in Cricket commented on his popularity owing to his honesty and decision-making ability. Reflecting the respect held for him, both Hertfordshire (in 1895) and the MCC (in 1906) gave him benefit matches, although the latter was a little disappointing.

Around November 1906, Titchmarsh began to suffer what was later reported as both a “serious illness” and “nerve trouble in both legs”. Quite what was diagnosed is unclear, but he was treated at University College Hospital for a time. As the year progressed, it became clear that he was seriously ill and that his case was “hopeless”. It was reported in July 1907 that an old cricketing colleague had visited him at home, where he was showing no signs of improvement, and Titchmarsh said that he did not expect ever to make it onto the cricket field again. The same report said that he was suffering from “locomotor ataxy” and had “lost the use of his lower limbs”. He died at his home of 25 Liverpool Road (where the family had lived since at least 1891 and continued to live afterwards), St Alban’s, on 11 October 1907. His death was registered by his daughter Annie and the cause was listed as “Locomotor Ataxy” and “Exhaustion”.

The cause of death is interesting. The illness, now known more as locomotor ataxia, was often associated with the effects of tertiary syphilis known as tabes dorsalis. The main symptoms are difficulty walking, and a lack of awareness of the position of arms and legs. Titchmarsh’s brief profile on ESPNcricinfo makes the link explicit, saying that he died of syphilis. And despite this association, Wisden had no hesitation in listing the cause of death as locomotor ataxy in his obituary in the 1908 edition; it is the only such mention of that illness in any Wisden obituary. However, while there was an undoubted link, there were (and are) other causes for locomotor ataxia; the NHS website lists many possible causes. If linked to tertiary syphilis, it is likely to arise long after the initial infection: generally between ten and thirty years, but possibly sooner. The person may not be contagious for most of this period.

There are no obvious signs of anything that affected his family. His wife and children went on to have long lives with no signs of illnesses such as congenital syphilis. This does not rule out something that he contracted long before he married, but does suggest that the cause of his locomotor ataxia may have been something else. We cannot be certain either way; to say that he died of syphilis is unproven. But even in photos showing him in his late forties reveal a striking, handsome figure: it is far from impossible that, in his younger days, he had some wild adventures; he would not have been the first young cricketer to do so, and he would not have been by any means the last.

Titchmarsh left £328 15s to his wife in his will (worth around £35,000 today). The 1911 census records that his widow and two daughters (both of whom were working as shop assistants at a draper’s) still lived at 25 London Road. Eliza, who completed the census return, made a mistake and filled in the section on her marriage, revealing that she had given birth to one child who had not survived. Eliza died in 1937, aged 76, at Westcliffe-on-Sea, leaving just under £1,200 (worth around £78,000 now) to her two daughters.

In March 1915, Titchmarsh’s older daughter Annie married a man called Frederick Farr who was a grocer at the time and later became a company director. The 1939 register, taken when Annie was 52, records them living at Southend-on-Sea; living with them was Annie’s sister, the 50-year-old Lilian, who was unmarried and has “no occupation” listed. Annie died at the age of 64 in December 1951, at Westcliffe-on-Sea, leaving just over £6,200 to her husband; the couple do not appear to have had any children. Lilian died, also at Westcliffe-on-Sea at the age of 94 in September 1983.

If we cannot be certain how Titchmarsh contracted his fatal illness, it is possible that there were whispers around the time of his death, not helped by the publicity in newspapers. But these whispers are unrecorded by history, and perhaps no-one was too concerned. In any case, more important should be what was recorded: that Titchmarsh was a respected man and an excellent umpire. To his contemporaries, that was all that mattered.