Samuel Richardson in 1874 (Image: CricketDerbyshire)

Samuel Richardson was an early hero of Derbyshire cricket. As a gentlemen’s outfitter, he was a prominent figure in Derby; when Derbyshire County Cricket Club was formed, he captained the team’s first first-class match in May 1871 and led the side until 1875. As a batsman and occasional wicket-keeper, he played 15 first-class matches for the county between 1871 and 1878. After this, he served as honorary assistant secretary until 1889; from the mid-1880s, he combined this position with a similar role at Derby County Football Club. His cricketing statistics are unremarkable and after his death in 1938, at the age of 93, he merited only a brief and bland Wisden obituary. But there is one curiosity: he died in Madrid, which at the time was literally the front line in the Spanish Civil War. Although Wisden is silent on this unusual location, the explanation lies in a scandal from almost fifty years earlier: in 1890, Richardson fled England with his family to avoid being arrested for embezzlement. For at least ten years, he had been taking money from Derbyshire, from Derby County and from the men who employed him as a tailor.

Subsequent investigations by the county uncovered instances of Richardson’s fraud dating back at least ten years; his good reputation and a lack of scrutiny from an overly trusting committee allowed him to escape notice. His disappearance was a big story at the time, and it is one of those tales where facts can be difficult to establish. Although any lingering notoriety attached to Richardson arises from the money he stole from Derbyshire, the cricket club were not his only victims. Some of his other actions can be traced through court cases by his former employers, who attempted — generally in vain, but often ruthlessly — to recover some of their money.

Richardson was born in 1845 in Derby, the third son of Thomas Richardson, a tailor. In 1866, he married Mary Ann Archer and by 1881 the couple had six children, all of whom were girls. Other than this, little information is available about him; the 1881 census lists him as a “master tailor employing sixteen men and three boys” and the family employed a servant at 40 Babington Lane in Derby.

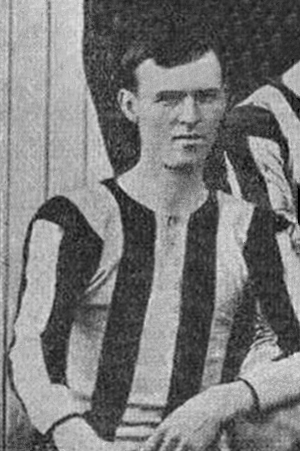

South Derbyshire v the “Australian Aborigines” in 1868: Samuel Richardson is the wicketkeeper

(Image: The History of Derbyshire County Cricket Club (1989) by John Shawcroft)

As a cricketer, there is little to relate. In the 1860s, he played mainly for South Derbyshire whose home ground later became — and remains — that of the Derbyshire County Cricket Club. While playing for South Derbyshire in 1868, Richardson faced the team of indigenous Australian cricketers, generally known as the “Aboriginal cricket team”, that toured England that summer. Although he accomplished little in that match, he achieved something during an interval in play that no-one else did that summer: he was the only English cricketer who successfully met the challenge of Jungunjinanuke (better known to cricket history as “Dick-a-Dick”) of landing a blow on his body with a thrown cricket ball.

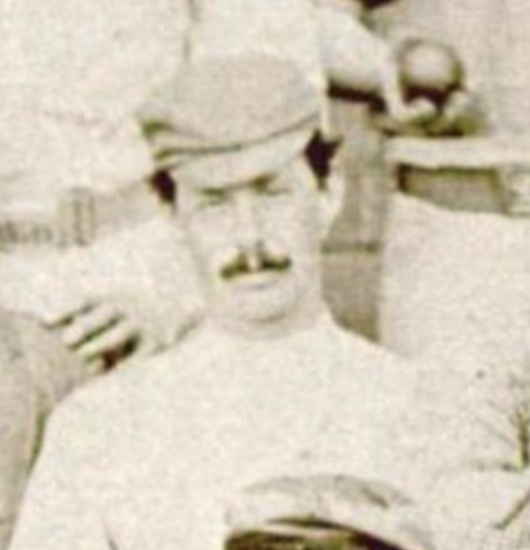

The prolonged success of South Derbyshire in the 1860s inspired the formation of Derbyshire County Cricket Club at a meeting in 1870 at which Richardson was present (although some newspaper accounts of the meeting call him “F. Richardson”). He was appointed as the team’s first captain and between 1871 and 1878, he played in fifteen first-class matches for the county, with a high score of 25 and an average of 7.48. Until 1884, he occasionally captained the Derbyshire Colts, a team comprising young cricketers being given a trial. Off the field, he remained at the forefront of cricket in the county; in 1880, by which time his playing career was largely over, he was appointed as Derbyshire’s assistant honorary secretary.

Although details are scarce, Richardson also seems to have been directly involved in the formation of Derby County Football Club in 1884; it was created as an offshoot of the cricket club and he was its first secretary. The only other concrete fact from this period is that in 1884, Richardson sold his tailor’s shop to a company called Thompson and Sons. There was little practical change as the Thompsons employed Richardson to manage the business, which continued to operate under his name — “Messrs Richardson and Co” — at the same address of 1 Babington Lane.

Other than this, we must make some educated guesses about what happened. Based on what emerged when Richardson fled the country, he appears to have stolen money from Derbyshire and Derby County throughout the 1880s, although the only contemporary mention of problems at the football club came at a tense meeting of the cricket club in 1890. The Derbyshire Committee discovered that over the course of several years, Richardson had been offering tickets for football and cricket matches and then keeping the money for himself; he was also under-reporting the attendances at matches (in the days before turnstiles) and pocketing the excess gate money.

Derbyshire XVI which played the United South of England XI in 1874: Samuel Richardson is seated in the middle row, third from the left

(Image: The History of Derbyshire County Cricket Club (1989) by John Shawcroft)

Furthermore, the end of the 1880s was a fraught time for Derbyshire off the field; the county lost its first-class status after 1888 and even before Richardson’s disappearance had been heavily in debt on more than one occasion. Although no link was ever made — and it was hardly unusual then or later for a county club to find itself in dire financial straits without any fraud involved — there may be some connection with Richardson’s activities. Additionally, by the the late 1880s, there were calls for Derbyshire to employ a secretary instead of leaving the position as an honorary one — something that many counties did in this period. Therefore in October 1889, Richardson resigned his position and William Barclay Delacombe was appointed as Derbyshire’s first paid secretary. Again, there was no suggestion that any suspicion was attached to Richardson but it seems quite a coincidence that three months later he fled the country.

There may have been a hint of trouble unconnected to cricket in 1887 when “Messrs Richardson and Co” took John Lacey, the former manager of a local hotel, to court to recover around £20. The problem had arisen over Richardson’s approach to Lacey asking for donations to a money-raising bazaar; Lacey seems to have viewed this as a transaction rather than a donation and not paid a bill for some clothes, but the court ordered him to repay the amount. The case was slightly convoluted, and there was no suggestion of wrongdoing by Richardson, but with hindsight it is tempting to wonder if he frequently asked local businesses for donations which he pocketed for himself.

On 18 January 1890, Richardson disappeared. He was seen boarding the 2:05pm train from Derby to Nottingham, then nothing more was heard of him. The story was initially reported as a curiosity but by 12 February, the Derby police had issued a warrant for his arrest on a charge of embezzlement from his employers, the Thompsons. By then, the police believed that he was in Spain, but were “pretty confident of his ultimate capture”.

Thompson and Sons made no public comment until later in the year, but the annual meeting of Derbyshire County Cricket club on 25 February, and its associated report, was covered widely in local newspapers. This revealed the sorry state of affairs. The club was in a dire financial situation which the committee blamed almost entirely on “the frauds of their late honorary assistant secretary”. The meeting heard that Richardson had “according to his own admission” been stealing from the club for nine or ten years, but the committee thought it had been happening even longer.

“Not only has he secretly issued and received payment for a large number of tickets (both for cricket and football) for which he has not accounted, but he has also from time to time appropriated considerable portions of the receipts from matches. The great, but as now appears misplaced, confidence reposed in him, owing to his lifelong exertions on its behalf, of course enabled him to continue these frauds long after they would otherwise have been detected. The consequence it that the club is now in debt to the amount of nearly £1,000.”

This debt was most likely the culmination of Richardson’s actions rather than a sum that he pocketed before departing for Spain; he probably cost them considerably more than that over the ten years of his secretaryship.

Several people had come forward to offer the financial help without which the future of the county club would have been in serious doubt. The committee accepted that they had been at fault in not monitoring Richardson more closely but noted that his leading role in the initial formation of the club and his apparent enthusiasm and support meant that they could hardly be blamed for having confidence in him. There had also been problems with paying the professionals on the team, and several had not been paid immediately after matches, as had been the common practice; although this was not linked directly to Richardson, it is possible that he had been taking some of their wages.

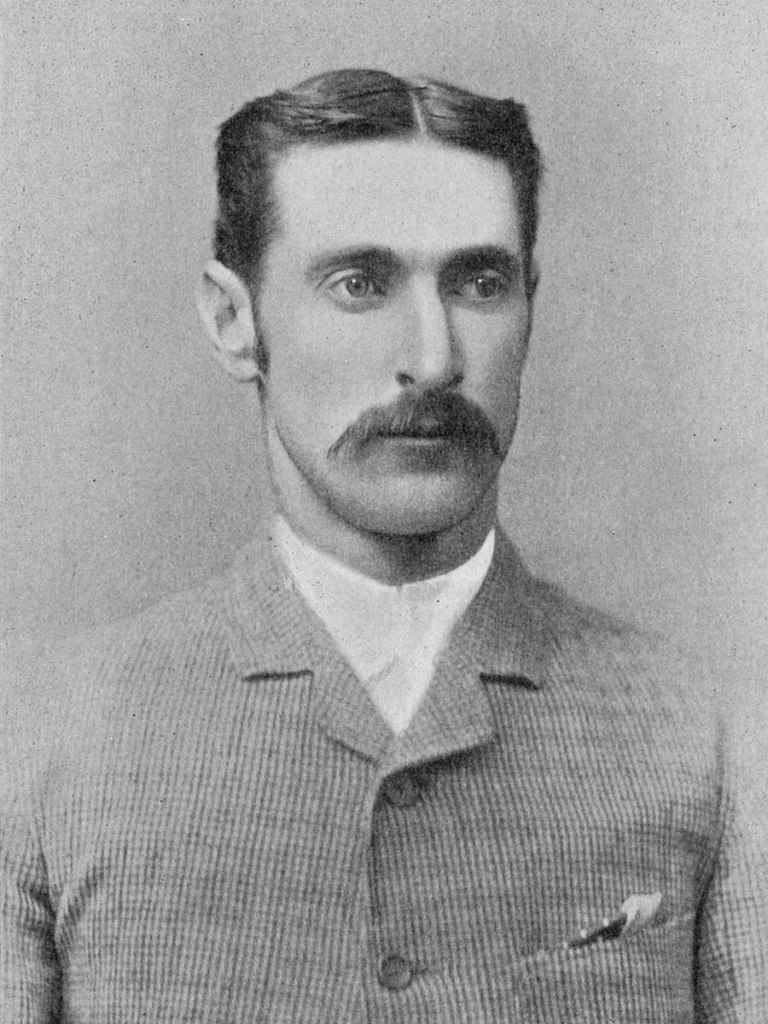

The full extent of the damage was uncovered by the unlikely figure of Frederick Spofforth. The Australian Test bowler, who toured England five times and took fourteen wickets in the infamous “Ashes” Test of 1882, had by that time settled in Derbyshire after marrying a woman from the county in 1886; one of his wedding guests was Samuel Richardson. Spofforth gradually became associated with the cricket club and qualified to play for the team, which he briefly captained in 1890. According to The History of Derbyshire County Cricket Club (1989) by John Shawcroft, Spofforth examined the club accounts in his spare time and found exactly how much Richardson had taken, and by what means.

The suggestion at the meeting that Richardson had admitted stealing for nine or ten years might indicate some form of confession. Assuming that if he had admitted this in person — for example when he resigned the secretaryship — he would have been arrested long before he vanished, perhaps Richardson left a letter when he fled the country.

However most later accounts of Richardson’s fraud overlook that it was Thompson and Sons who involved the police and had a warrant issued for his arrest. Over the next year, the company went to court several times in an effort to recover money he had taken, although their targeting of people who had been tricked by Richardson makes it hard to feel much sympathy for them. For example, on 24 June 1890 they took a widow, Mrs Stevenson, a linen draper, to the County Court to recover £9 14s. In 1886, she had bought some clothing from the company and paid the money to Richardson, who kept it for himself. But as she was unable to produce the receipt, the judge ruled against her, although he was sympathetic and said that it “made his blood boil to think of the rascalities of Richardson, and that he had not been caught.” One revealing insight was that around Christmas 1889, one of Richardson’s daughters had gone to Mrs Stevenson and pleaded with her to tell Mr Thompson, if he asked, that the account would be settled in a month; the widow agreed in order to protect the Richardsons. This may have been either a last desperate attempt to hide Richardson’s deceit, or a delaying tactic as he planned their escape to Spain.

In a similar case on 5 April 1892, the Thompsons unsuccessfully tried to recover money for several items of clothing from a surgeon called G. N. Edis who was able to produce a receipt signed by Richardson, which proved that the latter had kept £8 9s 6d of the money that Edis paid.

There was one other cricket link. In November 1890, the Thompsons took the former Derbyshire player William Mycroft to court to recover £1 they claimed he owed for two suits of boys’ clothes that he bought from Richardson in 1887. Mycroft produced a witness to say that Richardson sold him the clothing at a discount. There was laughter in the court when the judge said that he wished to see Richardson, and even greater amusement at a reply given by one of the Thompsons: “So do I, your honour”. After the judge found in Mycroft’s favour, Thompson said that he didn’t think it was fair that he had to pay costs as “I have suffered enough through this man Richardson already”, to which Mycroft replied: “But you have no right to make me suffer too.”

The Thompsons were frequent plaintiffs in court, in cases unrelated to Richardson, and it is likely that they pursued their claims vigorously. But there is no record of what happened to the company in later years, although it changed its name in early 1890, unsurprisingly dropping the “Richardson and Co” and trading as “Thompson and Sons”.

What happened to Richardson and his family afterwards is not entirely clear. The contemporary reports agreed that he had gone to Spain. Richardson’s Wisden obituary confirmed his death in Spain — although it offered no explanation for why he was there, nor mentioned the fraud which ended his association with Derbyshire. His death appears otherwise to have been unrecorded in the English press. However, the very fact that Richardson’s death was reported in Wisden suggests that someone was in contact with him or his family; someone clearly knew the story. The only apparent inaccuracy was that Wisden said he had died in March, whereas modern records give the date as 18 January. Wisden continued to list his death as March 1938 in its “Births and Deaths” section until the 1950s, after which it stopped being listed for reasons of space. Shawcroft wrote in his History of Derbyshire: “[Richardson] went to Spain, where he lived under an assumed name. Here he became court tailor to King Alfonso and lived to be 93 before his death in Madrid in 1938.” He also lists Richardson’s death on 18 January 1938, which might be the origin of that date; it would be interesting to know from where all his information came.

From here, we enter the realms of speculation and uncertainty. Two articles online indicate what happened to him in Spain, although neither gives any sources and therefore must be treated with a lot of caution.

The first is to be found on a website called “Great British Life” which hosts a 2009 article originally published on a site called “This is Derbyshire”. The anonymous author recounts the generally available tale, albeit omitting any mention of Thompson and Sons, and clearly makes use of reports about the Derbyshire meeting of 1890 for his information. The article relates how Richardson fled to Spain, but then adds to the picture: he was joined in Spain by his wife and “several of” his six daughters. According to this version, the family called themselves Roberts to throw off any attempts to trace them. The author continues:

“Nor was the former cricketer without a profession to fall back on — by trade a tailor, Richardson had established a successful gentlemen’s outfitters at 40 Babington Lane in Derby. This was to have a great bearing on his new life in Spain, for he opened an English-style outfitters in the centre of Madrid and made a great success of the business. Indeed he received the official patronage of the Spanish monarch Alfonso XIII (1886-1941), and as such Richardson grandly styled himself ‘Court Tailor to the King of Spain’.”

The author then makes a big leap. There is a well-known department store in Spain called “El Corte Inglés” which translates as the “English Cut”. The company website states that in 1935: “Ramón Areces Rodríguez bought a tailor shop founded in 1890 which is called El Corte Inglés”. According to the “Great British Life” article, this might indicate that the shop belonged to Richardson as 1890 was the date he fled to Spain. The author argues that by 1935, Richardson might have been struggling as King Alfonso was by then in exile. The article concludes:

Nor did the onset of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 help Sam Richardson’s cause, and he lived out his final years in relative hardship. The last few months of his life were spent in Madrid’s Anglo-American hospital, where he died on 18th January 1938 at the age of 93 years and 239 days … He was also declared by the Spanish press ‘Madrid’s oldest British inhabitant’. There ends the colourful story of a cricketer who yielded to temptation and was ‘caught out’. So Derbyshire’s first captain lies at peace in a Madrid cemetery far from the place of his birth. The death certificate names him John Roberts, but in the annals of Derbyshire cricket Samuel Richardson will always be ‘Spanish Sam’, who ran off with the takings and never came home.

A few years later, the online magazine The Diplomat in Spain carried a slightly different version of the story. This 2014 article by Alberto Rubio, which reuses parts of the 2009 article, makes the link with El Corte Inglés. It added the extra detail: “John Roberts — or ‘Spanish Sam’, as he was known since then in his hometown, Derby — could live comfortably in Madrid during the first third of the 20th century thanks to this distinguished ‘English cut’ that the well-off of that time liked so much”. Rubio adds: “The Spanish firm explains in its history that when its founder, Ramón Areces, came back from Cuba, he acquired ‘a small shop in the year 1935 in Preciados street, corner with Carmen and Rompelanzas, dedicated to tailoring and children’s dressmaking, whose name was El Corte Inglés’.”

Rubio’s article also includes a little more detail on the death of Richardson, suggesting that when he died, he “could not be buried at the British Cemetery of Saint Isidro, which at that time, during the Civil War, was in the middle of the defence line of the city.” But, according to Rubio, Richardson’s wife — under the name Mary Ann Roberts — and his daughters were buried there.

I have been unable to verify any of this information from Spain, nor is there any indication from where the authors of the two articles sourced their stories. The only corroboration for the link with King Alfonso appears in Shawcroft’s History of Derbyshire, which also stated that Richardson styled himself as the court tailor of the Spanish king. Whether this was ever true or simply an urban myth that added a little flavour to the story of Richardson’s escape is unclear. As for the Roberts family buried in Saint Isidro, we have nothing to prove that they were really the Richardsons, unless the death certificate of John Roberts (which I have not seen) makes an explicit connection.

Nevertheless, there is no indication from English census records or registrations of marriages and deaths that any of the family ever returned to England. Additionally, the use of one of Richardson’s daughters in the fraud of Mrs Stevenson might suggest that the entire family was involved in the scam.

A photograph of the interior of El Corte Inglés in Madrid, taken in April 1904. The original caption for the photograph stated (in Spanish): “View of the interior of the great tailor shop “El Corto Inglés”, the largest establishment in Madrid for children’s suits, and men’s coats and clothing. This building has been recently renovated and has a large number of doors and windows on three different streets.” (Image: Wikipedia, original photograph from Nuevo Mundo)

As for the link with El Corte Inglés, this appears based on little more than coincidence. From what is available online, it appears that the Spanish department store was founded in 1935 by Ramón Areces Rodriguez who, with the financial assistance of his uncle Cesar Rodriguez Gonzalez, bought a tailor’s shop in Madrid from a man called Julián Gordo. Another man, Pepín Fernández, may also have been involved (various permutations of who owned what are described online), but it is clear that no-one bought anything in 1935 from an elderly refugee from Derby. Other than the fact that the original shop was founded in 1890 (when it is unlikely that Richardson would have had enough money immediately to start another business), there is nothing to connect it to Richardson, nor any suggestion other than its name (which refers to a style of clothing) that it had any links with England. Nor was Richardson the only Englishman in Spain in these years. While it may make a nice story, there is no evidence to support it and the theory is not widespread (there are few Spanish references to it, and most draw on the 2009 article or the one in The Diplomat).

Even without this addition to the tale, Richardson’s story is a remarkable one. What drove him to do what he did, other than greed? There may be one little clue. One of the press reports which detailed the Thompsons’ attempts to recover their money gave a little of the history of their association with Richardson. Thompson senior “purchased the business from Samuel Richardson 1884, and also the book debts”. While “book debts” are simply the accounts of money owed to the business rather than a debt owed by the business itself, could it be the case that Richardson was struggling financially and sold up to the Thompsons? Based on the 1881 census, he had sixteen men working for him which would have been a big drain on his income. If several people owed money to Richardson, was he perhaps also in debt himself while he waited for them to pay? Was it financial desperation that led him to defraud the Thompsons as well as his cricket and football clubs?

Since Richardson disappeared, the story has been told as if he pocketed over a thousand pounds and escaped to Spain to live a life of luxury, like a nineteenth-century Ronnie Biggs. But given the length of time over which these frauds took place, the fact that he had to sell his business, and the generally small amounts that were involved in individual cases, it seems far more likely that Richardson was attempting to stave off bankruptcy, found himself far too deep in his deceptions and was left with no option but to run. The involvement of his daughter in a desperate attempt to delay his employers from discovering the truth over a matter of less than £10 might support the idea that panic rather than enrichment was Richardson’s main motivation.

However, if we can be fairly certain of the English end of the story, there is much about Richardson’s later life that is a mystery. Perhaps some answers may be found in Spanish sources, but there is almost certainly more to be uncovered about the assistant secretary who ran away.