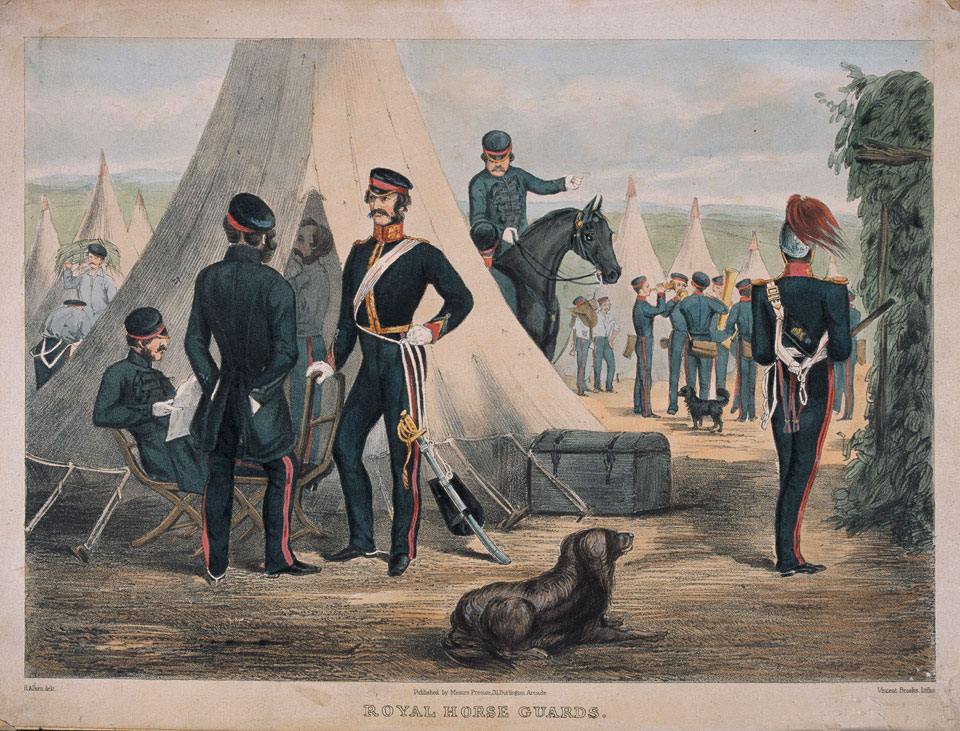

The Royal Horse Guards (Blues) in 1853 (Image: National Army Museum)

In the modern age, the arrest of the captain of an international cricket team would make headlines across the world and generate enormous discussion. Even more so if it took place during a match. And if that captain proved to be someone other than he claimed to be, the repercussions would be huge. And yet all those things passed almost unnoticed during a very low key tour of England and Scotland by a Canadian cricket team in 1880. Only a handful of spectators were present when the man — listed by newspapers and on scorecards as Thomas Jordan — was taken away during the first day of a match against Leicestershire by a sergeant in the Royal Horse Guards and some policemen. Apparently only one journalist was there to see it, but news travelled rapidly afterwards until everyone knew the reason for the arrest: “Jordan” was actually an Englishman called Thomas Dale, wanted for desertion from the Royal Horse Guards eight years previously. And when the details emerged, the story was a strange one.

The Canadians — referred to by CricketArchive as the “Gentlemen of Canada”, but all contemporary reports simply called them “The Canadians” or “The Canadian Team” — were one of two sets of cricketing tourists in England in 1880. Their fellow visitors were an Australian team led by Billy Murdoch. Whereas no Canadian team had visited England before, this was the second “official” Australian team to play in England. In hindsight, the summer was a vital one because towards the end of the tour — after a summer in which they found it difficult to arrange fixtures against quality teams — the Australians played a match against a representative English team which was later recognised as the first Test match played in England.

Owing to the sensational nature of “Jordan’s” unmasking and arrest, the events of the 1880 Canadian tour have proven irresistible to some modern writers and the tale has been retold a few times online or in print. However, these retellings often get important details incorrect. Contrary to the impression given by contemporary sources — and repeated in all subsequent versions of the story — “Jordan” was not the official captain. Instead, the team was nominally led by a 47-year-old cricket enthusiast, the Reverend Thomas D. Phillips. However, Phillips did not arrive in England until the fifth game of the tour, having travelled separately. In his absence, the team was led by the “sub-captain” (i.e. vice-captain), the man who called himself “Jordan”. However, another detail in modern retellings is pure invention, a twisting of the narrative to add drama. It has been suggested that “Jordan” was responsible for organising the team and did a poor job; as a result, the tour was chaotic and unsuccessful. But most of the arrangements were made by the player-manager H. Miller, who was still seeking opposition to fill the fixture list as the team left Canada. In fact, nothing is known about how the tour came about, whose idea it was nor from where its funding originated.

Rev. T. D. Phillips, the actual captain of the 1880 Canadian team (Image: The Canadian Cricketers’ Guide)

The inspiration was almost certainly the successful (and remunerative) tour of the United States and Canada organised by Nottinghamshire’s Richard Daft in 1879. But unlike Daft’s team, or that of the 1880 Australians, the Canadians lacked a certain legitimacy. Only four of the side had been selected for the recent match played between Canada and the United States, a semi-regular series dating back to 1844. And in late May, an apparently well-informed Canadian wrote a letter published in the English press that denounced the entire tour. He revealed that three of the team were living in the United States; seven were English emigrants to Canada; and only five were Canadian. He continued: “Every honest cricketer in Canada scouts the scheme as ridiculous in the extreme. The newspapers are all down on the undertaking, and hope steps may be taken to prevent their playing as the representatives of Canada.” He claimed that only one man (not, incidentally, “Jordan”) “plays well enough to be in a second eleven of county colts, therefore their reception [in England] has not been too enthusiastic”, and that the only hope of any success was that enough money would be taken at the gate to pay the team’s expenses and allow for “an enjoyable pleasure trip”.

There was one curiosity about the anonymous letter that might have raised suspicions had anyone been paying attention. The writer named several players when discussing where they came from; one of these, who he said was based in the United States, he called Dale. But none of the coverage of the tour in the British press listed anyone called Dale as part of the team. Instead, there was someone called “Jordan”; no-one apparently noticed the discrepancy and later writers missed the implication that the Canadians already knew that “Jordan” was the assumed name of Dale. However, the author of the letter was apparently unaware of the origins of Dale/Jordan; he did not include him in the list of English-born players, even though it would shortly emerge that he had been born in Yorkshire.

In the meagre early coverage of the tour, “Jordan” did not stand out. One early article, in the Dundee Evening Telegraph, called him “a most successful bowler and hard hitter, and one of the most thorough cricketers in America”. He performed well enough in the opening four games, taking 33 wickets in the first five games (at an average of around 10), including eight for 70 (and twelve wickets in the match) in then opening game and nine for 54 against Hunslet. He also scored 126 runs at an average of 18, including a fifty against Greenock.

“Jordan” was one of the few successes in the early weeks. The team arrived via boat in Glasgow in May and began the tour in Scotland. After winning their first match, against the West of Scotland, the Canadians drew against Greenock and lost to a team of former pupils of Edinburgh’s Royal High School. Moving into England, the team lost to Hunslet before playing the newly formed minor county Leicestershire — their strongest opposition to that point — in a two-day game beginning on 2 June 1880. The game took place at the ground now known as Grace Road, but then known locally as the Aylestone Park ground (after the area in which it was located).

Overnight rain delayed the start, and play only began at one o’clock. Two of the team — including the official captain, Phillips — had landed in Liverpool the previous evening and arrived in Leicester after play began, taking part as soon as they reached the ground. The only first-hand report on the game — and therefore the only account of the arrest — appeared in the Hinckley News. Leicestershire batted first and were dismissed for 168; “Jordan” took four for 49. When the last wicket fell around 5:15, the Canadians made their way to the changing tent that had been provided. Suddenly, a small group of men quietly surrounded “Jordan”. One of the group was Sergeant Walter Strange of the Royal Horse Guards, the others were plainclothes policemen. Strange, watching the game from the boundary with field glasses, had identified “Jordan” as a deserter from the Royal Horse Guards whose real name was Thomas Dale. As “Jordan” left the field, Strange confronted him, accused him of being Dale and said that he had come to arrest him. “Jordan’s” protestations of innocence did not convince the policemen, who arrested him and took him from the ground with a minimum of fuss. The tiny number of spectators (who numbered under twenty) might not have been aware of what was happening, but “Jordan’s” team-mates were shocked, having been unaware that he was a deserter (even if they had almost certainly known his real name). The shaken team slumped to 36 for six that evening. “Jordan” was replaced in the team with the agreement of the opposition the following day but more rain meant that the match was drawn.

After Jordan/Dale’s arrest, the tour stumbled on for around six weeks. The press were kind, making allowances, but concluded that Canadian cricket was simply not very good, particularly in comparison to the Australians. Two games in Wales were abandoned in the immediate aftermath of the arrest and results remained poor. The team lost heavily to Stockport, the Orleans Club and the Gentlemen of Derbyshire, although they beat the MCC and Surrey Club and Ground by playing with fifteen men against eleven. Even the use of local reinforcements, including the Nottinghamshire professional Walter Wright, could neither improve results nor attract spectators and the team was operating at such a heavy loss that money ran out. A few days after the Canadians played Stourbridge, the tour was abandoned and the remaining fixtures — of which there were several — were abandoned. The final record — played 17, won 5, lost 6, drawn 6 — was underwhelming given the low quality of the opposition.

Meanwhile, Dale faced the consequences of his deception and his desertion. The day after his arrest, he admitted his identity when he appeared before Leicester Police Court, charged with desertion from the 2nd Horse Guards (Blues) on 8 November 1872. It transpired that Dale had been recognised by an officer of the Horse Guards while playing in Scotland. Sergeant Strange had been sent to make the arrest and located him in Leicester. He was remanded in custody by the magistrates until he could be transferred to a military prison for his court martial.

Over the following days and weeks after the arrest, the story emerged in the newspapers, which were eager to report on the sensation. So who was the man who had called himself Thomas Jordan?

Duncombe Park estate in Helmsley (Photo © Carol Rose [cc-by-sa/2.0])

Thomas Dale was born in Helmsley, Yorkshire (although his family listed his birthplace as Rievaulx, a village three miles north-west of Helmsley, next to the ruined Rievaulx Abbey), on 25 December 1847. He was the fourth child of Thomas Dale — listed on the 1851 and 1861 census as an agricultural labourer (although “herdsman” is crossed out on the latter) — and Ann Alenby. The Sunderland Daily Echo gave an account of his earlier years which said that his father was the chief herdsman (censuses from 1861 certainly list him as a herdsman) of the Earl of Faversham, whose extensive family home, Duncombe Park, was located in Helmsley. Although no official sources corroborate this, the census lists the family living at Griff Lodge, which was on the Duncombe Park estate, so it is highly probable that Dale’s father worked for the Earl.

Dale’s military record shows that he enlisted in the Horse Guards in December 1868. Among the details listed were that he was 6 feet and ½ inch tall, with a “fair” complexion, grey eyes and light brown hair. In the aftermath of his arrest, newspapers tried to fill in the background of his time in the military. The Sunderland Daily Echo reported that he “soon became a favourite amongst not only his comrades in the ranks, but the officers as well.” It also said that he excelled in sporting activities, taking part in athletic competitions for his regiment. According to the Hinkley News, Dale was a particularly keen cricketer, and played the Horse Guards against the Household Brigade. The Sunderland Daily Echo reported that Dale had deserted at least one previous time, before his disappearance, after he failed to return to barracks having taken part in a sporting event; it claimed that he soon surrendered himself and was briefly imprisoned.

However, Dale’s military record paints a less wholesome picture. He served only 324 days as a private before his first desertion in November 1869, when he was absent for just over a month. He rejoined his regiment and was sentenced to a week of confinement. The day after his release, he went absent without leave. During this time, he was involved in an incident which resulted in him being arrested for assault; he served just over two months in a civilian prison. After his release in March 1870, he returned to his regiment — perhaps through choice but more likely involuntarily — and was tried once again for desertion. This time, he was sentenced to four months in a military prison. From July 1870 until November 1872, he appears to have served without incident before the final desertion from Windsor Cavalry Barracks on or around 8 November, after which he fled to the United States.

What happened next can be pieced together from stories that later emerged in the Canadian press. An apparently syndicated article published in Detroit in mid-June 1880 contained details of interviews with members of the Peninsular Cricket Club from that city. They said that Tom Dale had arrived in New Orleans in 1872. This can be corroborated independently because he was certainly in Mississippi, where he married an English woman called Rebecca Small, in 1873. The couple had one son but soon divorced (although there is no record of this). And it appears that Dale headed north from New Orleans because the members of the Peninsular Club believed that soon after his arrival, he found work with the mounted police in St Louis. The suggestion that he worked in some kind of law enforcement capacity was echoed by a report — perhaps copied from the Detroit source — in an English newspaper called The World, which indicated that he had operated close to the Mexican border.

A book called The Tented Field: A History of Cricket in America (1998) by Tom Melville includes a few more details, taken from newspapers, about Dale’s life at this time. According to Melville, Dale played professionally for cricket clubs in St Louis and Chicago; he also was given the nickname “Jumbo” because of his size. If we can believe the sources at the Peninsular Club, Dale moved to Canada soon after this; the Detroit article explained that he “had the temerity” to work as a professional for the British officers’ cricket team in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The World went a little further, stating that Dale had been “informally identified” in Canada when he was working as a professional bowler for the Halifax garrison, but “the interests of good cricket had been allowed to prevail over the strict claims of military law, and so he had remained a free man”. However, this might have been a creative reinterpretation of what the members of the Peninsular Club had told the press.

How reliable the sources from the Peninsular Club might have been, they were on more solid ground with the information that in 1876, he moved back across the border to live in Toledo, Ohio, a city around 60 miles from Detroit. And according to their version, in 1877 he accepted a position as a professional cricketer at the Peninsular Club. Possibly their chronology is a little muddled because we know that Dale was married in Toledo in 1878, to a native of that city called Mary Ann Herr. Perhaps he only returned for the wedding.

The 1880 United States census lists Dale and his wife living in Wayne, which was part of Detroit, Michigan. By then, the couple already had two children. However, he gave his occupation as a “truckman”, suggesting that reports that cricket was not his main source of income. Nevertheless, we know that he played for several cricket clubs in this period. CricketArchive records some of appearances for the Peninsular Club, including games against the Australian team that had toured England in 1878 (which travelled home via the United States) and Richard Daft’s team the following year. And the members of the Peninsular Club told journalists that at the time of his arrest, Dale was living with his wife and children in the “Keeper’s House” at the cricket ground.

Clearly, Dale must have been a successful cricketer. There are also indications from the press reports after his arrest that he had played for Canadian clubs, which might account for his invitation to join the tour of England in 1880. For whatever reason, he accepted. By any measure, it seems a strange and unnecessarily reckless decision, particularly if he had indeed been recognised in Halifax. If he hoped that by changing his name, he would avoid detection, he had not reckoned with the determination with which the British army pursued deserters. What made the decision even more baffling was that, according to the article in The World, Dale had been a well-known cricket figure before his desertion, and was easily recognisable on the field owing to his unique bowling action. Therefore it had been an incredible risk (“thrusting his dead into the lion’s mouth” as The World phrased it) to return to England.

When he was indeed recognised while playing in Scotland, it was inevitable that Dale would be arrested. But one syndicated newspaper article published in the United States in mid-June 1880 offered an alternative explanation for his identification. It suggested that Dale had left an English wife when he fled to the United States. According to the article, she had pursued him across the ocean and had him arrested for bigamy following his American marriage. This avenging wife accepted money to divorce him and promised not to reveal his presence to the authorities, but went back on her word and passed on the information that led to his arrest. However, this appears to have been a purely dramatic invention; Dale never married in England (although his first wife was English) and no other contemporary article mentions the involvement of any angry wife. There is no evidence one way or another to indicate whether Dale’s marriage to Herr was bigamous. Yet modern writers have accepted this explanation and indicate that an angry wife reported Dale to the authorities. While not impossible, it seems unlikely.

After Dale had been uncovered and arrested, he spent a few days imprisoned in Leicester before the military authorities arrived. The Leicester Journal reported that, on 8 June: “A party from the 2nd Royal Horse Guards (Blues) arrived in Leicester from London to escort the Canadian cricketer, Dale, back to his regiment, to be tried by court martial. There was a large number of people at the gaol to witness the departure. A cab was used to convey the party to the station, and drove away amidst cheers from the spectators, the cricketer bowing in return.” Ironically, there might have been more people to watch Dale being taken away than watched any of the Canadian team’s games of cricket.

Knightsbridge Barracks as it would have looked in 1880

The only account of what happened next appeared in the Sportsman on 21 June, sourced from a “correspondent” and widely reprinted over the following weeks. Dale’s court martial was held at Knightsbridge and he was sentenced to 36 days in prison. But while in the guard room, he managed to escape until he was recaptured by a civilian. Therefore, another court martial was held immediately and another 300 days added to his sentence. Not every newspaper unquestioningly accepted this tale; for example the Liverpool Albion expressed doubts and suggested that if the tale was true, the officer in charge of the court martial deserved the strongest criticism as the second sentence was vindictive. And his military record tells a slightly different, more likely story: when he was tried after his arrest at Leicester, there is no indication of any attempted escape after sentencing. Instead, his sentence was for exactly 11 months (which amounted to the 336 days reported). Nor would 36 days have been a realistic sentence for someone who had previously already served over two months for desertion. The 1881 census records Dale as an inmate at Millbank, at that time operating as a military prison, with an occupation of “soldier and carman”. He was, curiously, listed as unmarried. Upon his release on 16 May 1881, he was discharged from the Royal Horse Guards; his record listed his “character on being discharged” as “bad” owing to his desertion and civilian sentencing. The cause was listed as “his incorrigible and worthless conduct”. His total service amounted to just three years and 117 days.

With that, Tom Dale disappeared from the newspapers. But he can be traced over the following years through his cricket and through official records, because he returned to live in the United States for the rest of his life. He and his second wife continued to live together, and had more children — nine in total — of whom at least four were born after his release from prison. Dale also resumed playing cricket; he appeared for various teams between 1882 and 1895, including Detroit and Chicago, and made a single first-class appearance when he represented the United States against the Gentlemen of Philadelphia in 1883. According to local obituaries, he also coached the Detroit Athletic Club and was a good swordsman and boxer. The Peninsular Club gave him a benefit in 1883.

By the time of the 1900 census, he and his family were living in another part of Wayne. Dale was listed as a “mailbox repairman”. But the marriage was not a happy one by this stage. His wife began divorce proceedings against him for cruelty in 1904, and the divorce was granted in 1906. No further details are available but between his repeated desertions and his imprisonment for assault in 1869, this divorce is hardly indicative of a sympathetic character. Dale remarried almost immediately. His third wife, Catherine Ashley, was a Canadian thirty years younger than Dale; the wedding took place in Prince Edward, Ontario, but it is unclear whether Dale was living in Canada or went there only for the marriage. By the time of the 1910 United States census, he and his wife had returned to Wayne; Dale was working for the Post Office as a repairman and the couple had a child. A second soon followed — Dale’s eleventh. The 1920 census records the 73-year-old Dale working as a Post Office clerk. He died in February 1921: his cause of death given as senility and he was listed on the death certificate as a master mechanic. He was survived by all of his wives.

Dale’s story is a strange one, and largely inexplicable given how little information survives. Was he a rogue who tried to be too clever? Was he a man whose love of cricket drove him to recklessness? Tempting as it is to imagine this scenario, it is more likely that something else lay behind not only his ill-fated homecoming in 1880, and his odd and convoluted route through the United States and Canada between 1872 and 1880. Unless more sources can be found, the full story will never be truly understood.

Another fascinating article! Regarding the origins of the tour, it seems to have been planned at least a year in advance… I happened to come across a brief article in the Glasgow Evening News of 23rd June 1879, stating the secretary of the West of Scotland CC had received a letter from Montreal (writer not name in the piece, sadly!) and negotations for the match in Glasgow were already underway.

LikeLike