Fourth on the list of leading Yorkshire wicket-takers in first-class cricket is George Macaulay, a bowler who is largely forgotten by everyone today. He took four hat-tricks in his career, but if his name is noticed these days it is because, in an undistinguished Test career, he took a wicket with his first ball. There are many strange and interesting things about George Macaulay, but very little has been written or published about him, certainly since his death in 1941. Perhaps his lack of success in Tests played a part, or his non-involvement in major issues of the time explain this. But given that only Wilfred Rhodes, George Hirst (about both of whom biographies have been written) and Schofield Haigh have taken more wickets for Yorkshire, his neglect seems a little puzzling. Never an easy man, it may be that Macaulay’s off-field actions have tarnished his career as a cricketer and may explain some uncomfortable silences in the cricket record.

George Macaulay came from a family which originated from Birkby in Huddersfield. His father, Charles Harold Macaulay, was born there in 1866 and originally worked in a mill; several Macaulays ran public houses in the area. Following the death of Charles’ father, he and four of his brothers moved to Thirsk in the late 1880s, where one brother, Kynaston, ran The White Mare. Charles and his brother George became professional cricketers, and were well-known locally as good cricketers.

Image from Thirsk Town Council website.

Charles married Ellen Horner, a Thirsk resident, in early 1897. The couple took control of the Commercial Hotel, where their first child was born around nine months later, on 7 December 1897, and named George Gibson, after Charles’ father; a blue plaque today marks the building. The family later moved to The Red Bear hotel. Apart from George, they had at least two other children: Charles Harold (named after his father) who died a few months after his birth in 1899, and Ethel, born in 1903. The latter had a cricket-themed wedding to a local cricketer, J. M. Lister, in June 1926.

Macaulay’s father, Charles, died in September 1909, when his son was just eleven. The following January, Macaulay enrolled in Barnard Castle School, almost 60 miles away. Maybe that was always the plan, maybe his father’s death altered the intentions. Barnard Castle, or the North-Eastern County School as it was at the time, was a large, well-equipped public boarding school, and if not in the top class of schools, seems to have been eminently respectable and was used to preparing pupils for university. An advert in the Yorkshire Post in 1909 states that the fees for the school were £13 per term, although later adverts suggest that this is a minimum fee. This would be worth around £1,200 today. This suggests that Macaulay’s family, even after the death of his father, were not poor and were respectable.

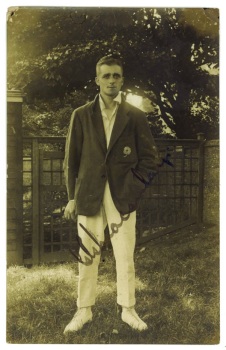

Macaulay evidently had some affection for his old school: each year, when he became famous, he took a team of Yorkshire cricketers, including household names, to play the school eleven. At Barnard Castle, he was a member of York House, in the Commercial form, and showed an aptitude for sport. By his second year, he was in the cricket first team, where he remained until he left the school. Something of an all-rounder, he was regarded as a good prospect. When returning to Thirsk during school holidays, he played for the local club, Thirsk Victoria, where his batting drew the attention of critics. But cricket was not his only success; he reached the school second team for football, and in internal competitions came second in a cross-country race, swam enthusiastically and won a bronze medal for life-saving, was a member of the Officer Training Corps, and was elected to the committee of his school house. He left Barnard Castle at the end of 1913.

Macaulay’s mother married again in 1912; she continued to run the Red Bear as Mrs Ellen Lee, with her new husband, James. According to a history of the hotel, in 1918 she bought The Golden Fleece at an auction for £4,000 (worth around £180,000 today) which she seems to have run by herself. Ten years later, she attempted to sell it and retire (having apparently given hotel a distinct motoring theme) but withdrew from the auction when the price had reached £8,750. She continued running it until 1936 when the hotel was bought (for an unknown sum) to a company, Trust Houses Ltd. She died in 1962, aged around 90.

Meanwhile, by his own later account, Macaulay worked as a bank clerk in Wakefield after leaving school. While there, he played cricket for Wakefield and Ossett. He also played football professionally in Ossett in this period. During the war, he served in the Royal Field Artillery as a gunner; he enlisted late in 1915, four days after his 18th birthday. Awarded the Victory Medal at the end of the war, he was discharged on sickness grounds in 1919. Macaulay then returned to his job as a bank clerk for the London County and Westminster Bank; first in London then in another branch in Hearne Bay, Kent. He must have played cricket in Kent, presumably as a fast bowler or all-rounder.

At the time, Yorkshire County Cricket Club lacked bowlers, particularly pacemen; Major Booth and Alonzo Drake, their two leading bowlers from before the war, were dead; George Hirst was ageing and losing effectiveness. Most of the bowling was in the hands of Wilfred Rhodes and, from 1919, Abe Waddington. There are two versions of how Macaulay became involved, both of which may have happened. Wisden, in 1924, claimed that Harry Hayley, a Yorkshire cricketer from before the turn of the century, spotted Macaulay in action. However, the former Yorkshire player and occasional captain Rockley Wilson, in his obituary of Macaulay in The Cricketer, said that Sir Frederick Toone told him that Stanley Christopherson, later the president of the MCC, saw him bowl in club cricket at Hearne Bay, and was the first to pass on the recommendation to Yorkshire. Wilson also suggests that Macaulay had a very promising career at the bank such that making a switch to professional cricket presented a considerable risk.

In any case, he was recommended to the club and made his debut early in the 1920 season. He had some success but his overall record – 24 wickets in ten games at an average over 20 – was poor for the time and he was dropped. Wisden’s damning verdict was that he “had neither the pace nor the stamina required” for a fast bowler. But Macaulay now had the taste for professional cricket and, mainly at the urging of Hirst and possibly Rhodes, spent the off-season perfecting the art of spin bowling, reducing his pace and increasing his accuracy.

Success came immediately. Now using two bowling styles – pace with the new ball, spin later on as conditions required – he took 101 wickets at an average of just over 17 in the 1921 season. Noting his improvement, Wisden praised his new style and immediately suggested that he may challenge for an England place. Among several effective performances against weaker teams, he took ten wickets in a losing cause against a strong Surrey team who were in contention for the County Championship. His batting was an unexpected bonus: he returned a healthy average of 22 (specialist batsmen occasionally averaged less than this during the period) and hit a century against another strong team, Nottinghamshire, to retrieve Yorkshire from a tricky situation. Having established himself, Macaulay continued to improve in 1922: another century, but more importantly, 133 wickets at an average just below 15 in 1922. This included startling analyses: six for 8 against Northamptonshire, six for 12 against Glamorgan. But these were against the weaker counties; the people that mattered in English cricket only began to pay attention when he took five for 31 against Middlesex at Lord’s, the home of the MCC and where cricket’s rulers held court. Performances against Middlesex mattered more to these people, and Macaulay was duly selected for the Players against the Gentlemen at Lord’s, a great honour at the time. He had a quiet match, but was included in the MCC team to tour South Africa that winter; not a prestigious tour, but once which included Test matches. There were, apparently, some who questioned his stamina for such an undertaking.

Macaulay had a mixed time in South Africa: lots of wickets against the minor teams; a wicket with his first ball in Test cricket; five wickets in the second innings of that debut game; but only nine wickets in the last four games. Wisden was rather scathing about the quality of the English bowling in general. But the trip did wonders for his health. His 166 wickets in 1923 were his best to date, he took a hat-trick and his average dipped below 14. With Roy Kilner, he established a commanding bowling partnership that swept most teams before it, supported by Waddington, Rhodes and Emmott Robinson. Macaulay’s performances took him to the brink of the England team when he was selected to take part in a trial game.

Pelham Warner, writing in the Cricketer annual following the 1923 season, was encouraged by the increased strength of English bowling following the disasters against Australia in 1921. He wrote (seemingly regarding Macaulay as a pace bowler pure and simple): “Macaulay, too, is a bowler whom I hold in high esteem – there is plenty of life in his delivery, and he bowls an uncommonly good slow ball … These three men [Macaulay, Maurice Tate and Arthur Gilligan] are on present form the stock bowlers of an England XI”. But somehow, the Wisden editor, Sydney Pardon was unconvinced. Discussing prospective candidates to take their place in the England team, he stated: “I think Macaulay is the most likely bowler who has not yet played in Test matches at home, but whether he has the right temperament for such nerve-taxing cricket is a question.” He chose Macaulay as one of his “Cricketers of the Year”, but even there complained: “His fault is that he is apt to become depressed and upset when things go wrong. His friends wish that he had a little more of Roy Kilner’s cheerful philosophy”.

[…] ‘Old Ebor”s posts about Macaulay begin here […]

LikeLike

An excellent summary of a complicated man.

The photo in part 1 from Thirsk TC website is incorrect as that website is incorrect. If you saw the blue plaque it says near here was born …The Commercial Hotel was pulled down and was where the space is to the left of the building you see. I was the Chair of the committee which installed these blue plaques and the owner of the building pictured gave us permission to put the plaque on the side adjacent to the gap. YCC honoured us by the Chair and archivist coming and unveiling the plaque (in the pouring rain) in the presence of several ex Yorkshire players.

In his latter years GGMc lived at Barkston Ash which is one mile from where I was born and live. I have been tapping into some memories of locals (albeight a bit late). My dad’s comment was that he drank a lot. His wife was the village hairdresser and in retirement went to live around Penrith (where she died) living with her sister. (since I have not yet found her parents or family I know no more about that.)

Re his death – I would like to know how the RAF admitted him if he was so ill, he must have passed some sort of medical , so I also cast doubt on that death certificate. I think that he must have some credit for a man of his age and his various illnessses that really terminated his career to actually volunteer

Jan

PS Barkston Ash CC used to have a social competition between the ladies and gents and they played for the Macaulay cup.

He is remembered on the Barkston Ash war memorial and will be part of a display in our Church for Heritage open days that will include those from the 3 villages who lost their lives in WW2.

LikeLike

Thanks for replying. I’m fairly sure that the site of the plaque is the location of the Commercial Hotel based on some old OS maps of Thirsk. But thanks for the other information, and I’d love to hear of anything else you know.

LikeLike